This time last year, a heat wave was just beginning to spread across the Southwest. Record-breaking temperatures grounded planes and fueled wildfires, as residents of cities like Phoenix and Los Angeles struggled to keep cool and stay hydrated.

The heat waves were physically uncomfortable and in some cases proved fatal. But they were also expensive. For those already struggling to pay their bills, an unanticipated hike could be the tipping point into energy poverty.

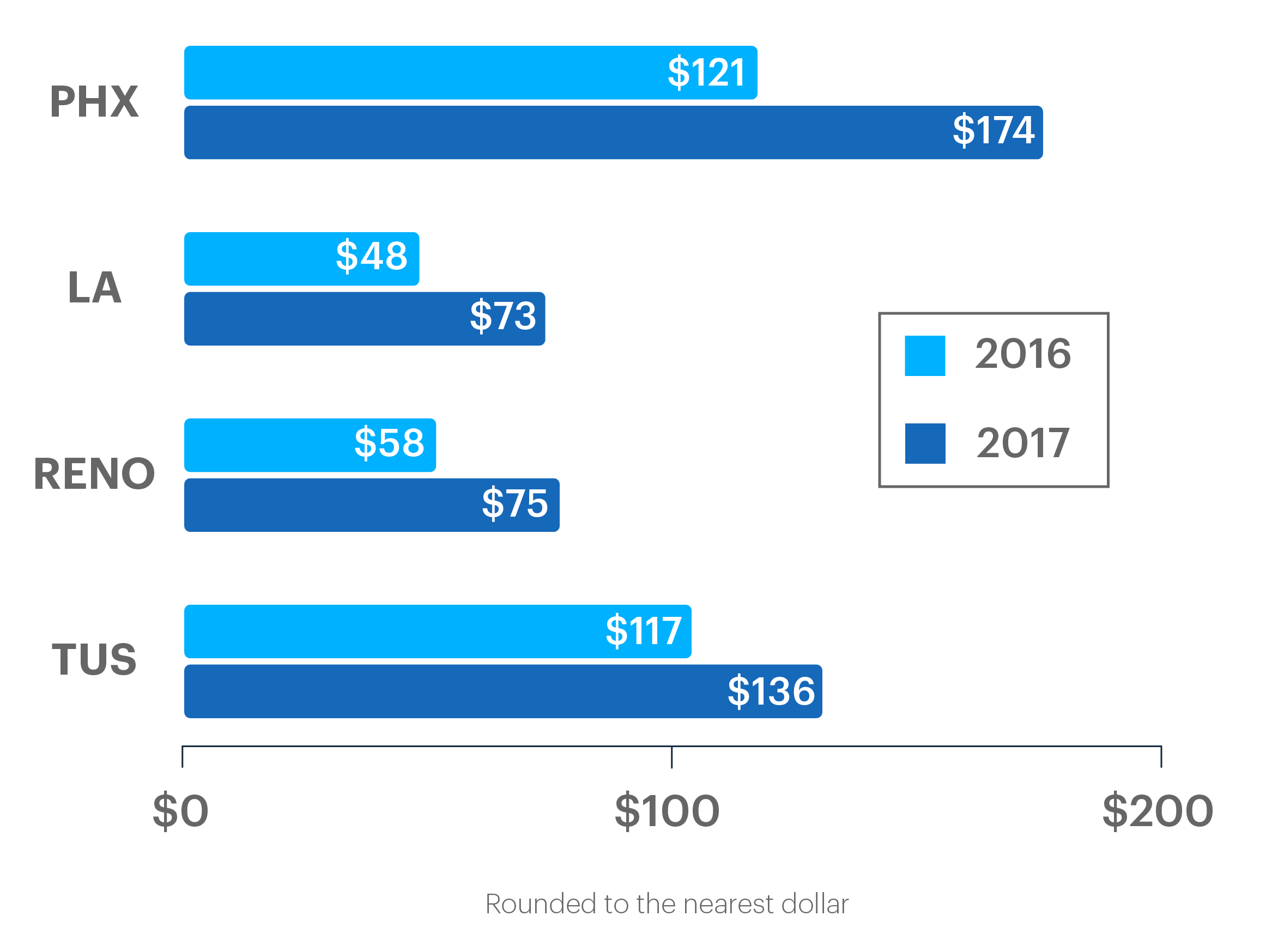

According to data compiled by renewable energy company Arcadia Power, people in cities across the Southwest spent up to 43 percent more on electricity in June of 2017, compared to the same month in 2016. The company manages the power bills of more than 100,000 customers across the United States, which means that Arcadia knows a lot about what people are spending each year to light, cool, and live in their homes.

With temperatures reaching 120 degrees in 2017 in Phoenix, Arizona, homeowners relied on their air conditioners to get them through the summer—but they paid dearly for the privilege. In June, households spent an average of $174 on electricity, compared to $121 over the same period in the previous year. That’s an extra $53. (It was also bad for the climate, with emissions per household also increasing by approximately 0.2 metric tons during that June.)

Arcadia’s data reveals a similar pattern in Los Angeles, where soaring temperatures also broke the city’s 131-year-old heat record. Residents used around 42 percent more electricity than they did the previous year, spending an average of $73 in June, compared to $48 in the previous year—an increase of $25.

(Chart: Arcadia Power)

“It’s clear when you have swings [in spending] this severe that these weather patterns are really taking a hit, both on the grid and all the way down to the retail customer,” says Kiran Bhatraju, chief executive officer of Arcadia Power.

Since the data only compares 2017 to the previous year, it’s worth bearing in mind that we have no idea what energy expenditures would be in a world without climate change. Indeed, 2016 was already the hottest year on record globally.

It’s not only individual increases in usage during times of extreme heat that cause spending to rise; heat waves also cause higher peak demand, leading utilities to raise the price of electricity to remain constantly equipped to deliver this increased supply. This was the case in Reno, Nevada, where spending rose by a larger proportion than usage did in 2017, thanks to a rise of 24 cents per kilowatt-hour, Arcadia’s data shows.

That’s a worrying pattern for consumers, considering that climate change is projected to increase the frequency and intensity of heat waves.

“We looked at this for a couple of reasons: to make sure customers understand the effect of climate change on their pocketbook, but also to help them understand the benefits of moving to a more resilient renewable distributed grid, as well as managing energy use at home, creating smart homes that have smart thermostats that can modulate energy usage at the right time,” Bhatraju says.

And there’s another cause for concern: Heat waves are more expensive for vulnerable members of society, says Ariel Drehobl, a senior research analyst at the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. According to a report she wrote on energy poverty in 2016, low-income households spent more than 7 percent of their income on utilities, more than three times the percentage among higher-income households.

Housing analysts say that 6 percent of total income is the point at which energy use becomes a burden. Energy poverty is commonly defined as 10 percent of total household income.

The higher proportion spent by low-income households is not simply down to energy bills eating up a larger lump of lower salaries. The households that Drehobl studied were also likely to be spending more in absolute terms, thanks to worse living conditions.

“Low-income households and communities of color are both more likely to live in older housing, which are more likely to have older appliances, which are less efficient and use more energy,” Drehobl says. Other factors, like lower access to energy-efficiency programs, also lead to higher spending.

Energy poverty isn’t just an issue during heat waves; some of the poorest people in the U.S. end up spending more than 50 percent of their income on energy over the course of the year, particularly in Montana, Alabama, and North Dakota, according to data compiled by Inside Energy.

But when heat waves strike, they can lead to a particularly cruel choice: stay cool, or stay solvent. It’s a decision that can be a matter of life and death. Heat-related deaths peaked in 2006, for instance, another year when widespread heat waves scorched the U.S.

There are measures that homeowners can take to reduce their bill, including taking part in community solar programs, installing smart thermostats, and improving the energy efficiency of their homes. Some 68 percent of the excess energy burden in Latino households could be eliminated simply by helping homeowners raise efficiency to the same standard as the average U.S. home, according to Drehobl’s report.

Heat waves are just one addition to a roster of environmental problems that will disproportionately affect the vulnerable and disadvantaged. Poorer communities are also more likely to face air pollution, and tend to suffer the worst damage when disasters hit, for example. As the summer heats up, these unexpected energy bills could cause the gap between the rich and the poor to widen.

New Landscapes is a regular series investigating how environmental policies are affecting communities across America.