Religion, goes the oft-paraphrased Karl Marx slogan, is the opiate of the people. Now, Wi-Fi is.This according to new research by Allen Downey, a computer scientist at the Olin College of Engineering in Massachusetts who analyzed more than two decades worth of the data on the demise of religiosity in the U.S.

Downey believes that the steady decline of religion is the result of several factors, including upbringing and education, but it’s the widespread adoption of Internet use in virtually every part of American life over the last 20 years, he argues, that has caused the most significant drop in religious affiliation.

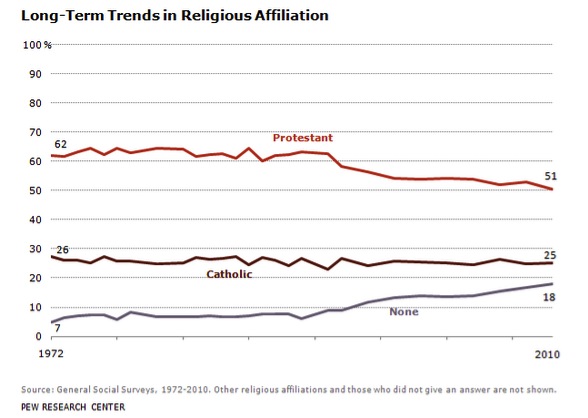

Based on data from the General Social Survey (GSS)—the University of Chicago sociological survey that has been used to evaluate the structure of American society since 1972—the heathens are taking over. In 1990, about eight percent of the U.S. population expressed no religious preference. By 2010, just two decades later, this percentage had more than doubled to 18 percent. And the rate is increasing: From 2007 to 2012 alone, the “unaffiliated” increased from just over 15 percent to 18 percent of all U.S. adults, according to the Pew Research Religion and Public Life Project; that includes 13 million self-described atheists and agnostics (about six percent of the U.S. population) and nearly 33 million people who say they have no particular religious affiliation.

(Chart: Pew Research Center)

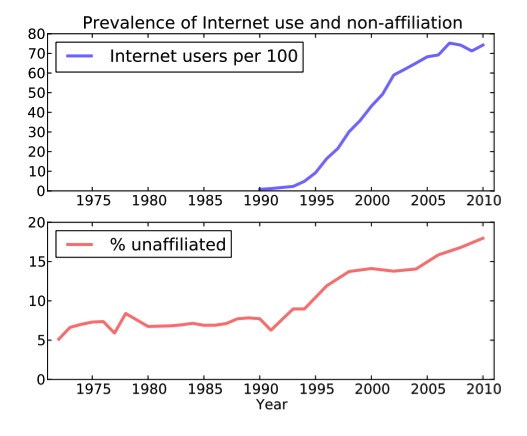

Downey’s initial discovery—that upbringing is among the most important factors in shaping future relationships with religion, and that those who are raised in religious households are more likely to practice as adults—should surprise no one. It’s his hypothesis that Internet use could account for 5.1 million people with no religious affiliation, or about 20 percent of the observed decrease in religious affiliation relative to the 1980s, that raises questions.

Internet adoption has exploded since 1995, when just 14 percent of American adults used it on a regular basis. Now 87 percent of American adults use the Internet, according to the Pew Research Internet Project. And according to the Downey’s chart below, the rise in religiously unaffiliated Americans seems to directly correspond with the rise in Internet usage.

So what is it about the Internet that makes it so toxic to faith? Modern history has positioned religion as fundamentally opposed to the Internet’s promise: knowledge, and the dissemination of information.

Since the Enlightenment, scientists and scholars both have predicted the eventual death of religion at the hands of reason. With the onset of modernity, as new tools of mass media made education and scientific knowledge more widely and readily accessible, whole populations were supposed to cast off their old superstitions and come into the light. American universities have been leading the charge for decades, with plenty of resistance (God and Man at Yale, anyone?), but the instant communication and collaboration promised by the techno-utopian heralds of the contemporary Internet were supposed to sound the death knell for the archaic rituals of human spirituality. “Where knowledge ends,” said 19th-century British statesman Benjamin Disraeli, “religion begins.”

Religious attendance rises sharply with education across individuals, but religious attendance declines sharply with education across denominations.

Unfortunately for them, the Internet didn’t kill religion in America. In fact, research suggests that the rise of the Internet—and the potential for mass communication it holds—may actually strengthen religious ties by providing new forums for religious expressions, whole digital churches for prayer and testimony. Nearly 25 percent of Internet users received religious or spiritual information online in 2001, with nearly three million people a day getting religious or spiritual material, up from two million the year before. “The Internet is a useful supplemental tool that enhances their already-deep commitment to their beliefs and their churches, synagogues, or mosques,” wrote researcher Elena Larson at the time. “Use of the Internet also seems to be especially helpful to those who feel they are not part of mainstream religious groups.” Not only have “older” identities such as religion, race, and nation been embraced online, but increased Internet access could be seen by many as primarily a means of repairing or reinforcing those allegiances when physical spaces—churches, community centers, and so forth—are not available or within reach.

Think of this as an inversion of sociologist Robert Putnam’s fear that, with the technological advances of modernizations, Americans would end up bowling alone. Putnam—who discussed his famous sociological study of American society and the concept of social capital with the Atlantic in a 2000 interview—pointed to the gradual “individualizing” of our leisure time through television and other technological innovations as an eroding force in American social life. In reality, a 2011 Pew study indicated that while 75 percent of all American adults are active in some kind of voluntary organization, Internet users are far more likely to be active and engaged in their communities. Three in five of all Americans surveyed said the Internet has had a major impact on the ability of groups to communicate with members and connect with others with like-minded interests.

What, then, is it about American society over the past two decades that has had a negative influence on religiosity? Even Downey admits that he isn’t positive. “We can’t know for sure that Internet use causes religious disaffiliation,” he told the Washington Post. “It is always possible that disaffiliation causes Internet use, or that a third factor causes both.”

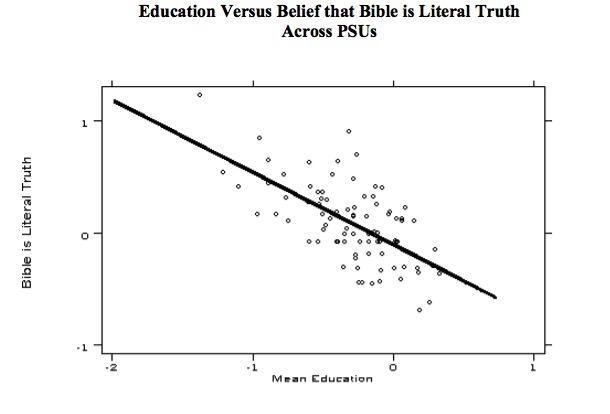

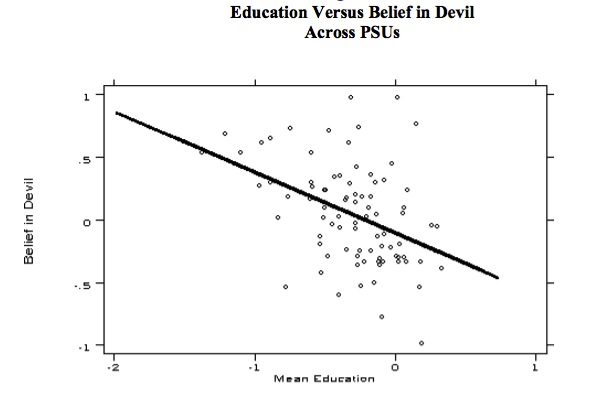

That third factor could actually be four or five or six; perhaps a combination of education, upbringing, and generational divides. Pew found near-saturation Internet usage among those living in households earning $75,000 or more (99 percent), young adults ages 18-29 (97 percent), and those with college degrees (97 percent): You could claim that those with a high level of education are likely to both use the Internet and to give up an affiliation with a specific religion. After all, one might be inclined to believe that education is a crucial factor in determining religious preferences. People with a higher education level are less likely to take the Bible as literal truth, according to a 2001 working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) by economists Bruce Sacerdote and Edward Glaeser. Same goes for the devil. Just check out the two ridiculous charts below:

Of course educated people know better than to buy into the mythopoetics of scripture, you might be thinking. But Downey’s analysis of the GSS data—the same source cited in the NBER paper—indicates that increases in college graduation rates between the 1980s and 2000s would only account for a mere five percent of the decrease in religiosity during the same period. Is a college education a weaker vaccine against faith than a wireless router or secular parents?

There’s a relatively simple explanation: Belief in God is not the same as a cultural or social relationship with religion, and neither are necessary conditions for academic failure. In reality, the mores and cultures that circumscribe different religions make for a far more complex and nuanced relationship between the classroom and the Sabbath dinner. But this answer, frustratingly, is a matter of nuance and context: The interplay between religion and education (and, in turn, religion and Internet use) is simply based on how positive or negative personal experiences.

In 1990, about eight percent of the U.S. population expressed no religious preference. By 2010, just two decades later, this percentage had more than doubled to 18 percent.

As Sacerdote and Glaeser’s NBER working paper shows, religious attendance rises sharply with education across individuals, but religious attendance declines sharply with education across denominations. “This puzzle is explained if education both increases the returns to social connection and reduces the extent of religious belief,” Sacerdot and Glaeser write. “The positive effect of education on sociability explains the positive education-religion relationship. The negative effect of education on religious belief causes more educated individuals to sort into less fervent religions, which explains the negative relationship between education and religion across denominations.”

Recent data (from Pew, obviously) confirms the uneven relationship between organized religion and education: The 2008 U.S. Religious Landscape Survey shows that Jews, Orthodox Christians, and Hindus are more likely to achieve graduate or post-graduate degrees than atheists, agnostics, and other “unaffiliated” respondents. “Even if religious upbringing affects college graduation,” Downey writes, “it does not explain the negative relationship between college education and religious affiliation or the decrease in religious affiliation over time.”

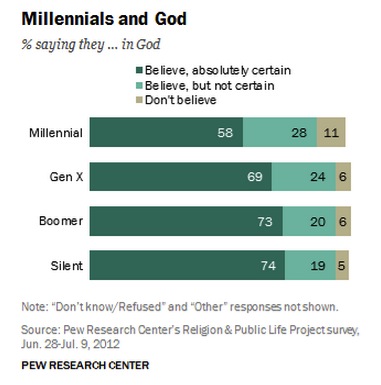

In the U.S., the answer may be further influenced by demographics: Yet another Pew Research Center survey shows that half of Millennials (50 percent) now describe themselves as political independents, and about three in 10 (29 percent) say they are unaffiliated with any religion. A solid majority (86 percent) still believe in God, but only 58 percent say they are “absolutely certain” that God exists, a lower share than among older adults, according to a 2012 survey by the Pew Research Center’s Religion and Public Life Project.

(Chart: Pew Research Center)

Outside of the U.S., the impact of the Internet is even less clear. A 2012 survey of religious belief in 30 countries—using the same GSS data repository as Downey—does show overall religious belief declining, but at a very slow rate. In countries with high rates of atheism, as people get older, they are more likely to become religious. And there’s no clear connection between Internet penetration rates and the rise of atheism. Globally, atheism is strongest in northwest European countries such as Scandinavia and those of the former Eastern Bloc (except for Poland), while the former East Germany had the highest rate of people who said they never believed in God (59 percent). None of these countries (except Germany) are in the top 20 nations for Internet penetration rate, according to data from the International Telecommunications Union in Geneva.

This isn’t to say that religious institutions shouldn’t worry about the coming disruption of the Internet: Let’s remember that one of the greatest political and social revolutions in modern history was spurred by Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses, which, once nailed to the doors of the All Saint’s Church in Wittenburg, Saxony, quickly went viral across the Holy Roman Empire and beyond thanks to the printing press.

Even the Vatican has embraced the World Wide Web as an essential tool for evangelization, “a new forum for preaching the gospel” (and yes, even His Holiness has a social media manager).

And the adoption of the Internet has given rise to new forms of spiritual engagement. (Consider the Terasem religious group in Melbourne Beach, Florida, that seeks to transform the human condition through radical advances in science and technology.)

The Internet is just another tool, not some aggregated monster-like state that graced the front of Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan, crushing churches across the English countryside. It doesn’t make you do anything: It amplifies your best and worst traits, all of which are shaped by your childhood, your socioeconomic status, and your education level, among other things. Whether Internet access unequivocally produces more atheists than evangelicals is unclear, and Downey knows this, reminding WNYC that the three factors of education, upbringing, and the Internet can explain only half the drop in religious affiliation, while no single factor can explain the other 50 percent.