For those of you keeping track, there’s yet another new potential threat to Internet users’ privacy: The Internet Corporation of Assigned Names and Numbers is considering a rule change that would make it much easier for people to look up the private contact details of website owners.

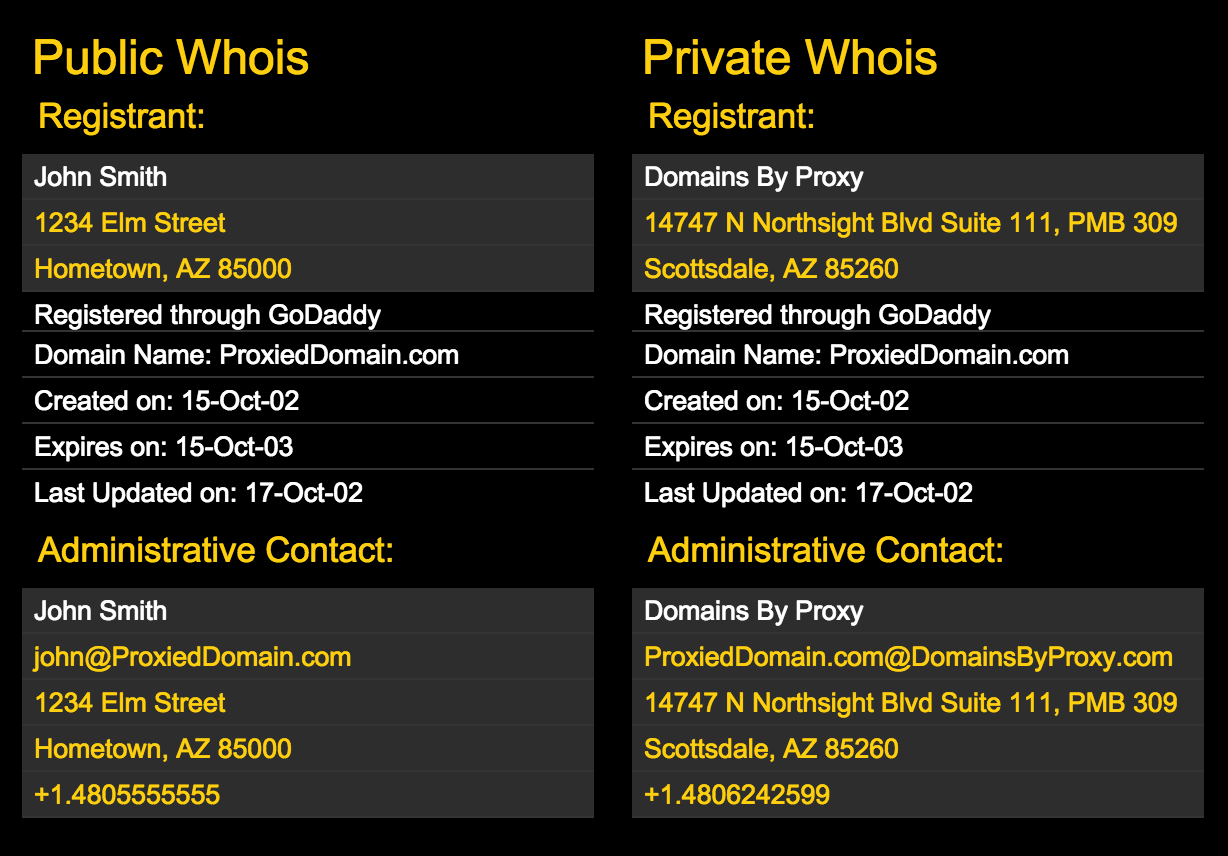

Currently, when users register a domain name on the Web, their information, including name, street address, and phone number is funneled into a publicly accessible registry listing known as Whois. In other words, that data is searchable, by any motivated party at any time, including spammers and hackers (and plain old “Women Aren’t Welcome on the Internet” harassers).

Rather than voluntarily doxing themselves, many individuals use proxy registration services, which post the proxy companies’ contact information into the Whois database, while privately storing each customer’s information.

The trouble is, many entertainment companies in the United States are pushing back against the widespread use of such proxy services. With the expansion of top-level domain names from a limited list of suffixes such as .gov, .edu, and .com to hundreds of new suffixes (including gems like .porn and .sucks), the major companies want to make it easier to fetch identifying information about users infringing on the company’s copyrights and trademarks. (For example, if I were to register Microsoft.pizza, or more likely, Microsoft.software, and try to make money off of the site by peddling computer software, or advertising, or even selling the domain name back to Microsoft Corporation, I’d get my pants sued off.) In a testimony before Congress in March, Steven J. Metalitz of the Coalition for Online Accountability explained:

Tens of millions of [generic Top Level Domains] registrations—one fifth or more of the total—lurk in the shadows of the public Whois, through a completely unregulated proxy registration system that is the antithesis of transparency. These registrations need to be brought into the sunlight. While there is a legitimate role for proxy registrations in limited circumstances, the current system is manipulated to make it impossible to identify or contact those responsible for abusive domain name registrations.

ICANN has released a proposal—now open for public comment—that would disallow the use of proxy services by any domains used for commercial purposes, which may include any sites that have ads. But in reality, these corporations are less of a victim than Metalitz suggests: Before ICANN opened up the new domain suffixes to average Internet users this June, the organization gave major companies a chance to buy up coveted top-level domains, as J. Wesley Judd reported. By March, Microsoft had already registered both Office.porn and Office.adult. But, according to Judd, such sites probably wouldn’t fool consumers anyway:

Research suggests, however, that these imposer URLs may ultimately not matter that much to said companies. A study by Microsoft Research revealed that searchers today are well-versed in the digital landscape and know how to spot a good URL from a bad one—in other words, they have a discerning eye and aren’t easily fooled. Office.porn just might strike the average searcher as a bit peculiar.

And the idea that it is “impossible” to identify users who use proxy services is patently untrue. Companies with legitimate cases can get a court order or subpoena to obtain the private contact information stored by the proxy services. It’s not surprising, then, that the proposal has been met with thousands of responses from users protesting the proposed rule change. “Private information should be kept private,” one respondent wrote to the ICANN: “Without these protections, the public—particularly individuals and small business owners—will be needlessly subject to scams, junk mail and con artists who prey upon those whose information is easily accessible in the public domain.”

But as one worried domain-owner pointed out, for some, the motivation to keep contact details private goes beyond the innate human urge to avoid spam: