It is the best of times, it is the worst of times — for penguins.

But like the French populace careening to apocalypse in Dickens’ “Tale of Two Cities,” the final outcome for the Adèlie penguins that ecologist Grant Ballard studies will be dire.

Ballard, the director of the Informatics Program at PRBO Conservation Science in Petaluma, Calif., has been studying the Adélies on Antarctica’s Ross Island since 1996. (A nonprofit, PRBO started in 1965 as Point Reyes Bird Observatory and now studies biodiversity conservation on land and sea.)

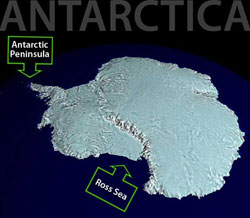

His research has determined that some colonies of Adèlies, those living near Ross Island, are going to be near-term winners of how climate change affects the world’s seventh continent. This will occur even as their peers on the Antarctic Peninsula 2,000 miles away face a punishing slog toward probable localized extinction.

“The colonies I study are doing very well right now,” Ballard explains, “and that’s nice, because they’re not doing so well in other parts of Antarctica, so it’s good that they’re doing well somewhere. We expect them to do so for a little time to come, but again, that depends on what climate model you choose. It could be as short as 20 years before they start facing some real challenges.”

Those challenges affect how they feed and breed, and in a land that really has no constituency among policymakers despite the charisma of its (few) denizens. But Adèlies are tough old birds, and they’ve survived past advances and retreats of the Antarctic ice sheet in the last 40 millennia or so.

“They’ve been able to adapt to large scale change previously,” Ballard notes. “If we could just give them a break, they may be able to do it again.” But the accelerated pace of anthropogenic climate change, and a newfound interest in Antarctic fisheries by humankind, may be a double whammy the Adèlies can’t avoid.

Grant Ballard’s mentor, the renowned penguin expert David G. Ainley, has dubbed Adèlies the “bellwether of climate change,” in part because they are completely dependent on the continued existence of sea ice and in part because they have been well studied and so provide a good baseline for observing change. (Ainley even used the “Tale of Two Cities” analogy in discussing differing fates of colonies just on Ross Island.)

And while they too troop across ice fields, Adélies are not the marquee bird in the popular documentary The March of the Penguins; that role went to their tuxedoed cousin, the Emperor penguin.

“Well studied” isn’t an easy proposition in the Antarctic, Ballard says, and no one had ever looked the Adelies’ entire migratory cycle before. “The fact that they’re out at sea, in the middle of pack ice, and it’s really dark, dangerous and expensive to study them at that time means that it hasn’t been done.”

The research he was part of — conducted between 2003 and 2005 by PRBO along with H.T. Harvey and Associates, Stanford University, NASA and the British Antarctic Survey, and funded by the National Science Foundation, Antarctic Organisms and Ecosystems Program in the Antarctic Sciences Division— involved fitting the birds with geolocator tags on their legs so the researchers could determine what the birds were up to, based on light levels and time, year-round, and not just in seasons congenial to human scientists. The results appear in the journal Ecology.

Modern technology helps, but is no panacea. You can rig the birds with satellite transmitters, as the researchers also did, but they’re big, bothersome to the bird, difficult to attach, often don’t work after a while and often pecked off or molted away. The much smaller geolocator tags are easier on the birds, and as long as they’re black and white they don’t automatically get pecked off, but they also require finding the same birds a year or two down the line to retrieve the tag and download its data. (The researchers are heading back this year for a closer look at individual bird behavior based on age and experience.)

Beyond the existential concerns, the research has uncovered some interesting information about the birds. Using ocean currents, Adèlies may make annual roundtrips of more than 8,000 miles, behavior the scientists think evolved as recently as the last ice age. And like many travelers, the birds hustle home on the return leg of the trip, moving about twice as fast as they go from their wintering location to their breeding spots.

“There’s a real urgency in what they did — they never waste any time,” says Ballard. “They’re at limits of what they can do — really in a hurry to get started, “to look for last year’s mate, to seek premium nest site. “Yeah,” he concludes, “I think they’re in a hurry to get home.”

That migration is the focus of concerns about the penguins’ long-term prospects in a warmer world.

The birds’ entire ecosystem revolves around ice, where it is and where it ain’t. When they’re foraging at sea, they need the ice as a place to rest and as a jumping-off and -in point for the buffet. These areas of open sea water surrounded by ice might, in summertime, see 15 to 20 percent ice cover; in the wintertime, as much as 80 percent.

But Adèlies raise their families on land, building nests of small stones on rocky outcrops and plains.

“It’s kind of a paradox for them,” Ballard acknowledges. “They reside in Antarctica, where there’s hardly any ice-free terrain, and yet they require that to nest.”

While that all suggests a rather fiddly species, Adèlies have shown themselves pretty robust.

Some boom-and-bust in their colonies has always occurred, and the birds’ natural curiosity, their tendency to explore, has served them well. “There’s a certain percentage of the population that’s always out there looking for a new opportunity, and they will settle in a place that looks like a good idea even if there are no penguins there,” Ballard says, adding, “and there’s usually a reason there’s no penguins there.”

However, those “test” colonies may be well placed for changing times.

While such flexibility may sound sensible to people, it surprised scientists. In another recent paper looking at Adèlies at Ross, researchers — including Ballard from PRBO, Ainley with H.T. Harvey, Oregon State University and Landcare Research New Zealand — documented penguins abandoning their traditional nesting sites when times there grew too hard.

“Witnessing large numbers of adult birds who have already successfully nested in one location switching to a new site in the face of environmental change has rarely been documented and is indeed surprising,” Oregon State’s Kate Dugger is quoted in a release.

While that sounds reassuring for penguins and their partisans, there’s a caveat. “Like animals living near the tops of mountains,” Dugger cautions, “polar animals have limited options if the planet warms beyond a certain point.”

In that vein, researchers are watching these adventuresome penguins wend their way south, toward the South Pole.

With warming, he said, those that are moving farther south will be the ones that find a new place that’s got the newest open water and the least competition for food and they’ll probably thrive. … “At some point — and it might be very close to where they are now, but we don’t know — they won’t be able to overcome that difference that they have to cover to get back to the wintering ground.”

Ballard says he thinks the birds could waddle the distance, but the associated risks and effort of jumping in and out of sea ice will create a limit. “They won’t adapt endlessly — I believe they’ve never ever been more than 20 or 30 kilometers south of where they are now,” he says, using mummified remains dating back 35,000 to 40,000 years as his boundary line.

The distance south also creates another problem for the birds — wintertime darkness in a place where the night is half a year long. The penguins on the Antarctic Peninsula are moving south to find sea ice in the winter, which puts them in longer and longer periods of darkness.

“But they also require light,” Ballard says. “They require light for navigating, and we think they require it for some aspects of foraging, although we don’t know for sure exactly why they need light because they forage very deep where it’s very dark. It seems they need to initiate dives when there’s at least some light.

“We know from other studies that they don’t move around at all when it’s dark or seriously overcast, so it seems they require some amount of sun or some concept of where the sun is to make long-distance migrations.”

“Ultimately penguins around Antarctica will face darkness or lack of ice — they’ll just reach that boundary from different directions,” he has said.

But in the Ross Sea, these are actually pretty good times for Adèlies since the hole in the ozone layer — remember that? — creates upper atmosphere cooling, which increases winds, which increases sea ice. Ballard calls it a “giant ice generator,” and as long as temperatures remain below freezing, it will likely remain one.

“People expect the ice to be going away, and fast, but in the Ross Sea it isn’t — yet. However, we do expect to in 20 years, or it could be 40 years, depending on which models you look at, we expect we’ll start seeing a decline in sea ice again, in the Ross Sea.”

The Antarctic, a continent, is not the Arctic, an oceanic system, despite their shared frigidity. Antarctica is holding a huge amount of landlocked ice, which is mostly reflecting sunlight back, which slows the rate of loss. The peninsula, however, is already seeing loss of sea ice.

“It’s a situation much more similar to the Arctic, and in those areas Adèlie penguins are disappearing already.” Flooding caused by warmer temperatures has been especially harmful for penguin chicks, which can’t yet “thermo-regulate” when they’re wet. In one case, a 2001 snowfall — although cold as heck, Antarctica is usually pretty dry and therefore not particularly snowy — was so big it buried thousands of adults on their nests. A similar freakish blizzard came in 2006, but it was later in the season and less devastating.

Although freakish, the historical record — based on mummified penguins — shows that weird weather like giant blizzards and giant icebergs and even localized appearances and disappearances of Adèlies has occurred before. Disappearances on the Antarctic Peninsula, at least of small colonies struggling in less optimal places, are occurring now, as ecologist Bill Fraser has documented (and The New Yorker‘s Fen Montaigne reported on in December.)

But climate change isn’t the only human-caused woe for the birds.

“They have other challenges with fisheries coming in more and more now, too,” Ballard says. “There’s sort of the double whammy of climate change and increased human extraction, especially with fisheries. The penguins [which eat krill, small fish and squid] don’t necessarily compete directly with the fishermen, but the ecosystem as a whole does. We’re concerned about what happens to the system when you start removing — as we have everywhere — the top predators, the big fish.”

Ballard and the other researchers are providing information to a member of the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, the one organization with the statutory authority to create non-fishing areas off Antarctica. The convention is planning to examine that possibility in the spring. The researchers have also provided information to the nongovernmental organization the Antarctica and South Ocean Coalition, which supports a marine protected area for the Ross Sea, as this video titled “The Ross Sea, Antarctica” suggests.*

While Ballard isn’t taking a public position on what the convention should do, because the Antarctic is pretty much the last accessible place on Earth that hasn’t been completely altered by humanity, he is concerned about a potential loss that echoes beyond Adèlie colonies.

“From a scientific perspective, it’s a tragedy to lose this place, last reference point.” Ballard laments. “From a cultural perspective, a human value perspective, I think people can understand it’s probably not a good idea to destroy every ecosystem on the planet.”

*The Antarctica and South Ocean Coalition supports marine protected area status for the Ross Sea ice shelf. An earlier version of this story incorrectly said they had not yet taken a stand.