The 43 people who died when the Steelhead Haven neighborhood and surrounding homes and roadways in Snohomish County, Washington, were buried beneath mud this spring were victims of the nation’s deadliest landslide. Survivors recalled a thunderous bang, like that of a plane crashing, followed by a breaking away of the hillside and the sound of trees being snapped—as houses seemed to explode amid a wash of earth. One resident told the Seattle Times that she noticed a crack widening at the top of the slope in the weeks before the tragedy.

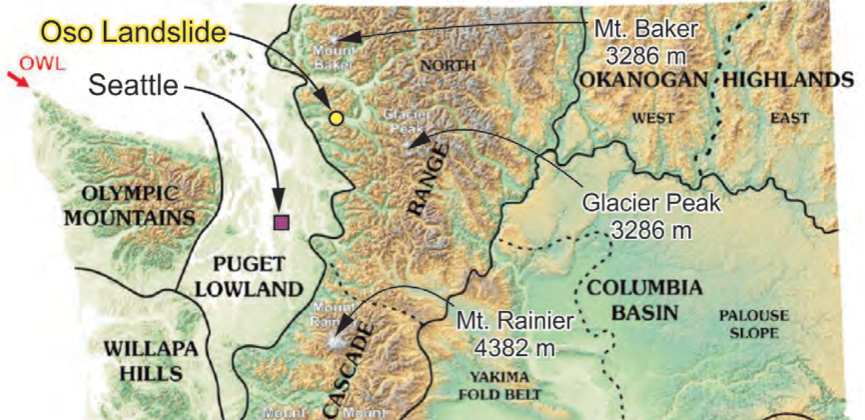

The March 22 landslide occurred during one of the region’s wettest Marches on record. But the sudden torrent of mud down the western flank of the Cascade Range was not unprecedented. Much of the debris that tumbled down appears to have been dislodged from its original location during similar events in ancient times. The Oso Landslide was bigger than any in the vicinity in modern times, but it occurred where smaller landslides have been documented. It entirely encompassed the site of one such 2006 event.

(Map: Geotechnical Extreme Events Reconnaissance Association)

In retrospect, it would seem that the 108 lots that were zoned for house building in the debris zone, nearly half of which had been built upon, shouldn’t have been. But how could anybody have grasped the dangers that were building beneath the saturating Pacific Northwestern storms?

Although “multiple studies identified the potential for a ‘catastrophic’ failure affecting human safety and property” in the area, there had never been any formal efforts to assess the probability of a landslide in the North Fork Stillaguamish River Valley, scientists with the National Science Foundation-supported Geotechnical Extreme Events Reconnaissance Association wrote in a report published Tuesday. “We are not aware of any predictions that the debris from a landslide in this valley could run-out thousands of feet across the valley floor like it did in the 2014 event.”

Monitoring systems that are in place in landslide-prone regions abroad, such as in the Alps, for example, and that are used in open pit mines, were not being used. Such systems are dangerously absent from vulnerable regions across the United States. It’s unclear how they could have been effectively deployed to provide advance warning of the looming March landslide anyway. That’s because geologists have only a limited understanding of the precise role that groundwater saturation can play in triggering such tragedies.

The report contains recommendations for preventing such disasters in the U.S. in the future, many of them focused on improving science and technology:

- Landslide monitoring and warning systems need to be developed and deployed.

- Methods for identifying potential landslide runout zones should be reevaluated.

- The history and behavior of past landslides should be investigated before creating zoning maps.

- Risk of landslides should be assessed, and such assessments should be continuously updated using new data.

- These assessments should take advantage of recent advancements in Lidar imagery and high-resolution aerial photography.

- Landslide risks should be “communicated clearly and consistently to the public.”