In October of 2015, an aging underground natural gas storage well, located in the Aliso Canyon Oil Field in Los Angeles County, blew out and began spewing its contents into the air. Four months passed before operators were able to plug the leak; during that time, 8,000 local families from the nearby Porter Ranch neighborhood had to evacuate. It’s thought that the leak sent up to 109,000 metric tons of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere—roughly equivalent to the annual methane emissions of the entire Los Angeles Basin. The Aliso Canyon Oil Field methane leak would go on to become the largest of its kind in American history.

The catastrophe got Drew Michanowicz, a research fellow at Harvard University, wondering: Were the conditions that led to the Aliso Canyon well failure really all that unique? After about a year of gathering data on all of America’s underground natural gas storage wells, Michanowicz and his team of Harvard environmental health and law researchers arrived at an answer: no.

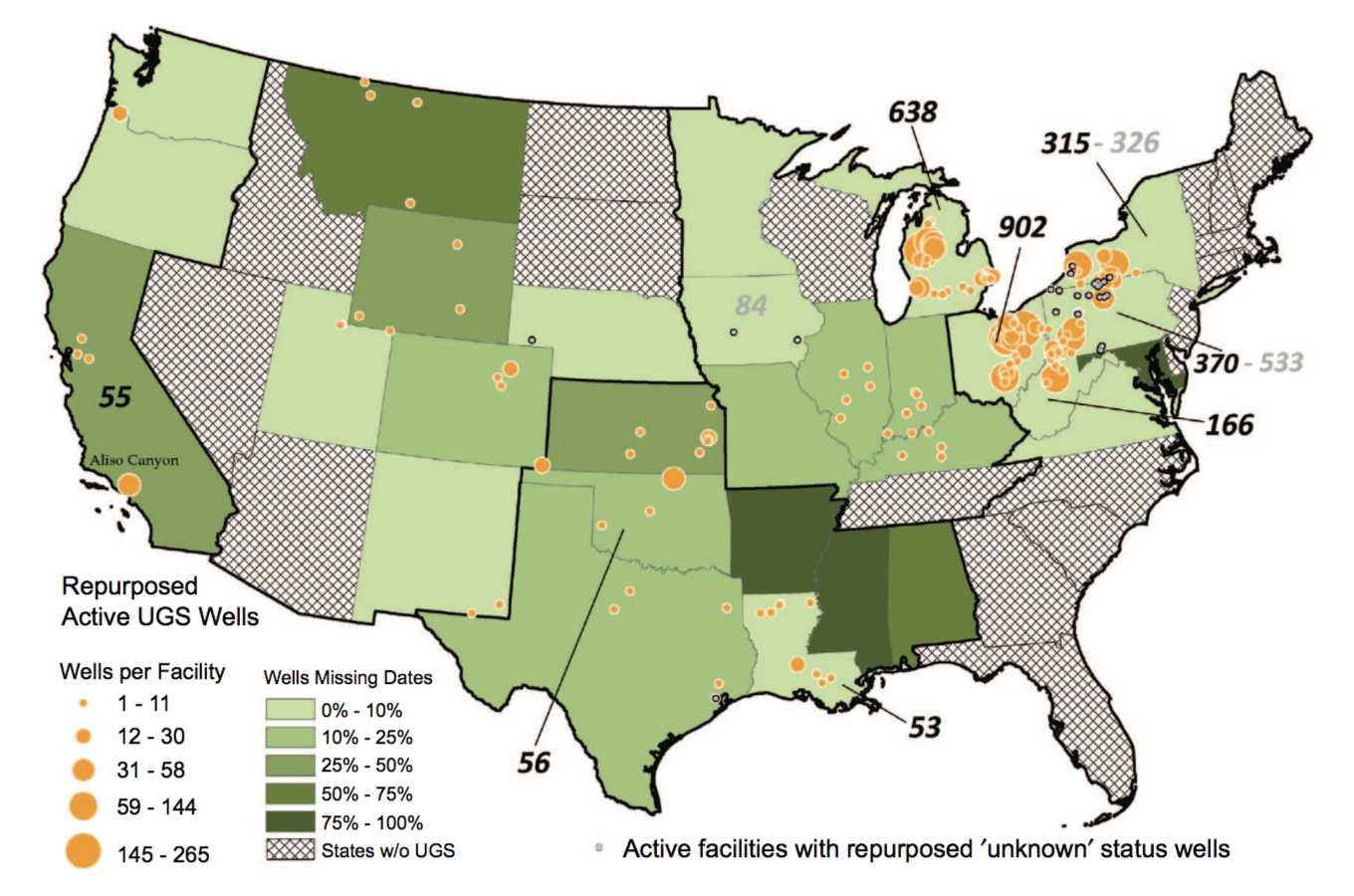

The team identified more than 14,000 active gas storage wells across America. One in five of them, or about 2,700, may be at risk for leaking because—like the failed Aliso Canyon well—they probably weren’t originally designed to store natural gas, and were constructed before 1979, when important modern building techniques became widespread in the gas industry. Two hundred and ten of those wells were built before 1917, and so may be missing numerous safety features.

“Those are the wells we think are the highest priority, which we would want to investigate how well they’ve been managed,” Michanowicz says. “If a single well at one of these facilities can fail and leak for four months, then significant precautions should go into mitigating this kind of thing from happening again. The hazards are so grave.”

Natural gas leaks can trigger health problems for nearby residents; at Aliso Canyon, people complained of headaches, nausea, and nosebleeds. Leaks contribute to climate change by releasing methane, a gas that warms the climate by 86 times as much as carbon dioxide. They waste a resource that provides a third of the United States’ electricity. And although this didn’t happen at Aliso Canyon, there’s potential for large fires, which have followed past, smaller leaks. “Our energy decisions are health decisions,” Michanowicz says.

He’s not the only one worried about these wells. In 2016, a federal task force, convened in the wake of the Aliso Canyon blowout, wrote that older gas storage wells are less likely to have extra barriers against leaks and are more likely to have corroded over time, while wells that hadn’t been originally built to store gas may not be designed to deal with gas’ high pressures. The task force recommended the industry phase out older storage wells that don’t have at least one extra leak barrier.