If things stay as they are, Cape Town will become the world’s first major city to run out of water.

This is the reality: Most of the city’s water is supplied by dams. The dams are currently three-quarters empty. On the day the dam levels reach 13.5 percent of their capacity (known otherwise as “Day Zero”), the city’s taps will be shut off. According to the City of Cape Town’s projection, Day Zero will fall in April.

From that point on, residents will be obliged to queue for a daily water ration of 25 liters per person (or about 6.6 gallons) at one of 200 collection points throughout the city. Water will still be supplied to hospitals, clinics, “essential services,” and standpipes in informal settlements, but most people will simply have to wait in line for their water, not unlike how people wait in line at the pharmacy or McDonald’s. Cape Town has a population of four million people, well over half of whom are expected to rely on the collection points dotted throughout the 154-square-mile city. This means 10,000 to 15,000 people will be lining up at each collection point, every day, for an unguessable amount of time; it could be a week, three months, 150 days.

Around the city, questions have continued to mount: How does a queue of that size work? What happens to all the people who can’t queue, or who don’t have any way of carrying enough water for a family home with them? What sort of infrastructure is required to manage long daily queues of panicked people? In a city divided along stark racial and economic lines, how will the sites of the collection points be determined? What happens to the city’s water-borne sewage system? What happens when people start getting sick? What happens when they start getting very sick? The logistics of the crisis are confounding, all the more so because there is no point of comparison for this situation.

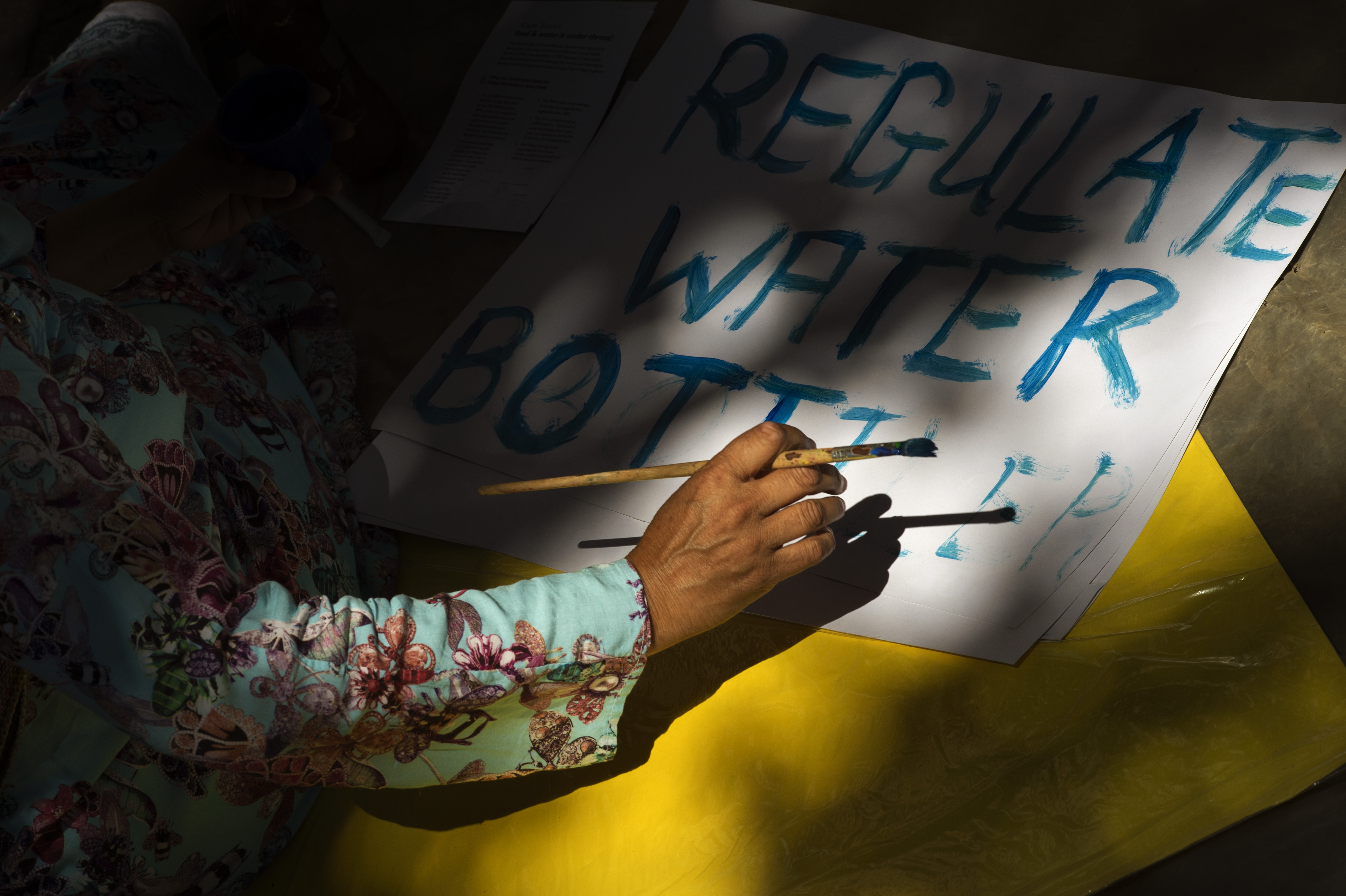

(Photo: Rodger Bosch/AFP/Getty Images)

At the moment, the emergency plan seems unfeasible; even some city officials have tacitly acknowledged as much. Discussing the water collection points, a member of the city’s mayoral committee, JP Smith, said that “it would be catastrophic if we end up having to collect water at [collection points]…. We must not think that it is a viable solution for long. It is, at best, an emergency solution, and should be avoided at all costs.”

Other officials have been more evasive about the degree of trouble the city now finds itself in. Ian Neilson, the deputy mayor and newly appointed head of the city’s emergency drought management team, responded with bewilderment in a recent interview to questions about the city’s preparedness for Day Zero. “If those are all Day Zero questions, this is the wrong time to ask me,” he said flatly. He then cut the interview short.

Other official efforts at communication have been inconsistent, contradictory, and overwhelmingly hampered by the factional crisis taking place within the Western Cape’s ruling party, the Democratic Alliance, and by extension the political system as a whole. Among the many political squabbles that have emerged in South Africa in recent weeks:

- The city’s mayor, Patricia De Lille, appears to have lost the trust of the DA, and has recently been removed from her role in managing the city’s response to the drought.

- The African National Congress, the country’s ruling party, issued a statement describing Day Zero as “a DA invention that translates to nothing more than an unnecessary tool of rattling residents on a pseudo-judgment day rhetoric.” The Western Cape has historically been the only one of South Africa’s provinces to be run by the DA, but the protracted unravelling of the ANC has allowed the DA to gain a foothold in other parts of the country. Day Zero, and all the days that follow, has the potential to completely undermine what political credibility the DA retains. The ANC seems to have seized the welcome opportunity to embarrass their opposition.

- The premier of the Western Cape province, Helen Zille, attempted to frame the severe and prolonged drought as entirely unforeseeable, claiming to BBC that “the South African Weather Service have said to me their models don’t work anymore‚ in an era of climate change. … We all have to pull together when the experts can’t predict anything anymore.” (The South African Weather Service responded sternly—and effectively—enough: “Blaming the weather‚ or climate and the weather service is a cop-out for policy inaction and ineptitude in implementation of multidisciplinary research and reports that have long pointed to the water challenge in the country‚ the Western Cape and in Cape Town.”)

The official date for Day Zero sits now at April 16th. Other estimates place the date much earlier than that. Amid this uncertainty, there is the #DefeatDayZero campaign, which amounts to the message that Capetonians will squeak by, just, if everyone in the city sticks to a target usage of 50 liters of water (about 13 gallons) per day. For a middle-class person, 50 liters means showering for less than two minutes, flushing the toilet once, washing dishes once, washing hands once, and using water to cook once. Fifty liters means thinking about worrying over water all the time, and monitoring with suspicious eyes your friends’ and co-workers’ usage. It means thinking about water in the way Joan Didion does in her essay “Holy Water,” obsessing over “the movement of water through aqueducts and siphons and pumps and forebays and afterbays and weirs and drains, in plumbing on the grand scale.” Fifty liters per day is grim and uncomfortable; it’s hard to imagine a 25-liter limit.

(Photo: Rodger Bosch/AFP/Getty Images)

Yet as severe as the water shortage seems for the middle class, it’s decidedly worse for Cape Town’s low-income residents, many of whom already live with very limited access to clean, running water. For instance, the 2,422 households in the informal settlement of Masiphumelele are served by 233 communal toilets, with no drainage system. In Khayelitsha, a township with a population of 2.4 million, some families share toilets and others use open fields. For those people who live in townships and informal settlements, Day Zero restrictions, in combination with poverty, food insecurity, and already unsanitary living conditions, pose much more of an existential threat. Listeriosis, cholera, and typhoid are serious risks. As it is with every crisis everywhere, poor people will suffer the most.

Despite all this—all the headlines, all the political scandal, all the global concern—there remains a lingering disbelief among many Capetonians that Day Zero will ever actually arrive.

People are still watering their gardens and filling up swimming pools. Private enterprises and supermarkets continue illegally selling purified municipal water. Laundromats and hair salons are still in operation, and construction in the city center continues. Tourists are still streaming into the most beautiful city in the world, in the hottest months of the year, when water usage is highest. The Twitter account for Visit Sa, a prominent tourism company, recently posted a tweet drawing visitors’ attention to the opportunities for “a bath with a view” at one of Cape Town’s high-end hotels. The tweet has since been deleted.