As I wrote last fall, to move more deliberately toward anything resembling a sustainable future, we need to use land more efficiently, building more compactly, with higher densities of homes and businesses per acre than we built, on average, in the late 20th century. We particularly must do this in two circumstances: (1) by retrofitting or “repairing” what are now low-density suburbs with aging commercial buildings going out of service, and (2) by reinvesting and rebuilding in disinvested parts of central cities and older towns and suburbs. While I am on record as saying that we don’t necessarily need high densities to achieve these improvements, we certainly need to do much, much better than sprawl.

A growing segment of the market is ready for more urban environments, but for young urbanites to remain committed to city living and more walkable suburban environments as their life circumstances evolve, they will need higher quality urban places than we have offered in the recent past; and they will need relief from the sometimes harshness that unmitigated density can bring. It is the urban commons—the parks, plazas, streets, greenery, and public facilities we share or in which we have a collective interest—that have the greatest potential to provide these things. As I argued earlier this year, sustained success—and successful sustainability, for that matter—require that there must be a “there” to the neighborhoods, cities, suburbs, and towns we inhabit.

In my last article, I made the case why we must do better in nurturing and strengthening the commons. Today, I would like to discuss some beginning approaches, relying primarily on three sources that recently came to my attention.

START WITH STREETS

There is no better place to start than with our streets, our most plentiful and visible parts of the urban commons. And I would offer as a first principle that a street is not just a “street”; a road is not just a “road.” We have come to think of streets and roads as conduits, particularly for motorized vehicles: viaducts for getting us from point A to point B as efficiently as possible. Anything that slows us along the way is viewed as a detriment.

There are probably some roadways (inter-city freeways, perhaps; but not city streets, I would argue) for which vehicle travel efficiency is still a supreme goal. But that objective should not be allowed to define all streets, particularly in urban and suburban areas. My friend and street-design mentor Victor Dover, in an excellent essay on the subject for the just-published second edition of the Charter of the New Urbanism, reminds us that streets have historically been regarded differently:

Our society once created many different types of streets. A street was not just a conduit for moving cars and trolleys through, but also a place in its own right for socializing, entertainment, commerce, and for civic expression. Pedestrians (and their natural allies, the cyclists) ruled.

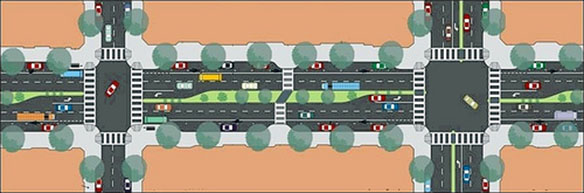

The recent and important “complete streets” movement has made a terrific contribution to getting our streets right, by insisting that they be designed so as to accommodate all users, from motor vehicles to pedestrians to transit users and bicyclists. Thanks to the movement’s efforts, this is now the law of the land in an increasing number of jurisdictions. It’s an important start.

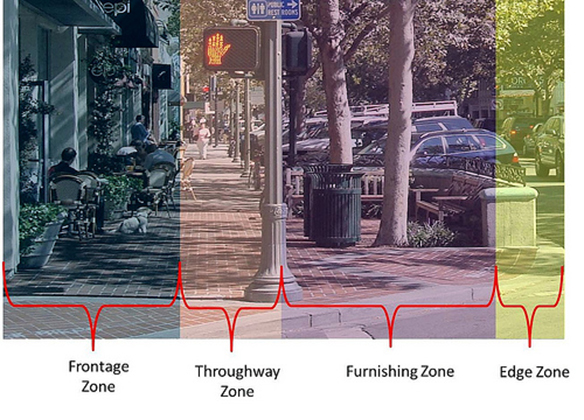

But, when I say that a street is not just a “street,” I mean that it is not just a surface for motorized travel. It is also the sidewalk, the curb, the trees, and “street furniture” that line it; the facings of the shops, homes, and other buildings and uses along the way. It is not just about transportation, but also about civic definition and social and commercial interaction. It is a system, at a minimum, and should at least aspire to becoming a place, as Victor asserts.

I have noted before that connectivity (small blocks and frequent intersections leading to a variety of places) is hugely important to a sustainable street network. The research demonstrates that street connectivity encourages walking and shortens driving trips by making destinations more conveniently reachable. In addition, the pedestrian experience should be safe and enjoyable, and should be so perceived. Steve Mouzon’s concept of “walk appeal” astutely notes that we will happily walk much farther if that is the case than if it is not.

Among other design elements recommended by Victor to help turn streets into worthy places are these:

• Sidewalks with real curbs;

• On-street parking to buffer pedestrians on the sidewalk from moving traffic, to calm traffic, and to reduce the need for parking lots;

• Street trees (whose many virtues I extol here);

• Storefronts with “encroaching elements” that shelter pedestrians such as awnings, arcades, and colonnades;

• Buildings with windows, doors, and “other outward signs of human occupancy such as porches and balconies” to allow “eyes on the street” and create a sense of safety;

• Design appropriate to safe motor vehicle speeds (instead of the current perverse and unsafe practice of designing streets and roads to handle traffic moving faster than the posted limit).

He strongly endorses the concept of complete streets but not so much all of the current practice:

[T]he physical designs have been rough and, for the most part, not at all beautiful, at least not yet. Perhaps it is because so many of these projects were undertaken as reversible, low-cost trials; perhaps it is because bike specialists are designing the cycle routes, transit specialists are marking the transit system’s space, and so on. Some of the streets have been bathed in an eye-popping riot of highway-style paint and signs and festooned with ugly white plastic sticks, all intended to show each user his or her own specialized bit of the street space in a loud, exaggerated way. This has not made for the best pedestrian experience and has not lent as much value to the great addresses of the city as they deserve. Gradually, as the quick demonstration projects give way to permanent reconstruction of the streets, one expects the eventual designs will be less overstated.

The best streets, Victor argues, require beauty, visual decorum, and a sense of completeness that “comes in large part from the dignity of street-oriented architecture and urbanism, not from signs and reflective stripes.”

Beyond streets, Victor argues that many past attempts to create urban plazas suffered from an indifference to local climate, culture, and activities likely to take place there. Instead, the design should be highly contextual:

The size and placement of squares should relate to their purpose and context. Their design image should be driven by climate, culture, and the activities likely to occur there. Plazas and squares should be located where they will be used—near cafes and storefronts, or in front of a courthouse, for example—and where they enhance real-estate value. Regional traditions should inform the choice between a soft, green space such as the village common found in small towns in the Northeast and Midwest, or the paved plaza found in Latin America, the Caribbean, or the Mediterranean.

Readers interested in a more complete and wonkier manual for good street design that strengthens rather than weakens the urban commons might want to consult the 215-page Designing Walkable Urban Thoroughfares: A Context Sensitive Approach, jointly published after years of collaboration by the Institute of Transportation Engineers and the Congress for the New Urbanism. Perhaps even better, Victor and John Massengale have a new book coming out, Street Design: The Secret to Great Cities & Towns, being published by Wiley.

A PROCESS FOR CREATING BETTER PUBLIC SPACES

When it comes to public spaces beyond streets (which are themselves infinitely variable and complex), it becomes much harder to identify particular design elements, since each place in the urban commons—each plaza, market, park, neighborhood square, shopping district, and so on—is different.

Indeed, the Project for Public Spaces, which knows a thing or two about placemaking in the commons, cautions against relying too much on design, or at least against starting with design. Instead, it has published 11 very useful principles for applying a process that can stack the deck in favor of success:

1. The Community Is the Expert (“In any community there are people who can provide an historical perspective, valuable insights into how the area functions, and an understanding of the critical issues and what is meaningful to people.”)

2. Create a Place, Not a Design (“The goal is to create a place that has both a strong sense of community and a comfortable image, as well as a setting and activities and uses that collectively add up to something more than the sum of its often simple parts. This is easy to say, but difficult to accomplish.”)

3. Look for Partners (“They are invaluable in providing support and getting a project off the ground. They can be local institutions, museums, schools, and others.”)

4. You Can See a Lot Just By Observing (“By looking at how people are using (or not using) public spaces and finding out what they like and don’t like about them, it is possible to assess what makes them work or not work.”)

5. Have a Vision (“It should instill a sense of pride in the people who live and work in the surrounding area.”)

6. Start with the Petunias: Lighter, Quicker, Cheaper (“The best spaces experiment with short term improvements that can be tested and refined over many years.”)

7. Triangulate (“If a children’s reading room in a new library is located so that it is next to a children’s playground in a park and a food kiosk is added, more activity will occur than if these facilities were located separately.”)

8. They Always Say “It Can’t Be Done” (“Creating good public spaces is inevitably about encountering obstacles, because no one in either the public or private sectors has the job or responsibility to ‘create places.’”)

9. Form Supports Function (“The input from the community and potential partners, the understanding of how other spaces function, the experimentation, and overcoming the obstacles and naysayers provide the concept for the space. Although design is important, these other elements tell you what ‘form’ you need to accomplish the future vision for the space.”)

10. Money Is Not the Issue (“Once you’ve put in the basic infrastructure of the public spaces, the elements that are added that will make it work [e.g., vendors, cafes, flowers and seating] will not be expensive.”)

11. You Are Never Finished (“Being open to the need for change and having the management flexibility to enact that change is what builds great public spaces and great cities and towns.”)

My favorites on that list, by the way, are numbers four, seven, and 11.

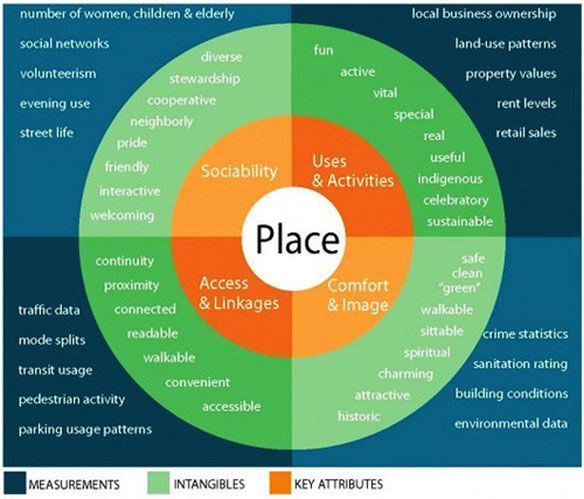

PPS also has a very useful matrix for evaluating the success of placemaking in the commons, which at first glance looks more complicated than it really is. “The Place Diagram” begins with the assumption that a good public space will be sociable, useful, comfortable, and accessible.

For each of the four basic attributes, the organization suggests both qualitative and quantitative indicators. With regard to whether a place is accessible, for example, one might ask whether, qualitatively, it feels convenient and connected to its community; and, quantitatively, how many visitors reach the site by walking or taking public transit.

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE URBAN COMMONS

Finally, Jay Walljasper, author/editor (with his colleagues from On the Commons) of How to Design Our World for Happiness: The Commons Guide to Placemaking, Public Space, and Enjoying a Convivial Life, approaches these issues from the perspective of a journalist. His latest book is a collection of articles from Commons magazine and other previously published sources, gathered into a single volume.

I don’t believe the book is publicly available yet (I was furnished with a pre-publication copy) but I would recommend it to anyone new to these subjects and looking for a broad, introductory reader on placemaking. In some ways, it reads like my own blog might read if I were a journalist producing shorter articles rather than a lawyer and policy wonk.

Longtime readers of my work will certainly find familiar subjects, including Enrique Penalosa, former mayor of Bogota and champion of designing for happiness; Ross Chapin’s “pocket neighborhoods” that feature shared space instead of homes with large yards; the wonderful Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative in Boston, restoring and enhancing a low-income community; intersection-painting as a way of bringing neighborhoods together; romantic cities; Danish architect Jan Gehl’s principles for walkable placemaking; the Jardin du Luxembourg in Paris, “the gold standard by which to measure urban parks”; New York’s High Line; and the relationship of the spiritual to the city. Walljasper and I have never met, at least not in person, but it’s rather obvious we like a lot of the same things. His writing tends to be shorter and less wonky than mine, which many readers may find appealing.

There are also some important and intriguing topics in Designing Our World for Happiness that other writers have not highlighted, including the special significance of public spaces to the poor, and the relationship of private spaces to the commons. I especially liked a short article about a resident who, following his own version of PPS’s “lighter, quicker, cheaper” principle, installed a bench for passers-by in his front yard, facing the street. It reminded me of Steve Mouzon’s essay some time back on “giving to the street“; there are delightful possibilities along that edge between the public and the private.

I also liked an article on an approach to neighborhood improvement that capitalizes on the community’s assets rather than taking the remedial path of attempting to identify and overcome its deficiencies. And, even though I have written about faith and the city, Walljasper’s short interview with Reverend Tracey Lind, dean of Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Cleveland, is illuminating on the subject of how places of worship can enhance the urban commons.

You’ll have to find and read the book, of course, to learn what Walljasper believes to be “the best neighborhood in North America” and “America’s most surprising city.” Watch for an announcement on the On the Commons website.

This post originally appeared onNRDC’s Switchboard, a Pacific Standard partner site.