Africa’s Congo Basin is home to the second-largest rainforest on the planet. But according to a recent study, this may soon not be the case. It finds that, at current rates of deforestation, all primary forest will be gone by the end of the century.

The study was conducted by researchers at the University of Maryland who analyzed satellite data collected between 2000 and 2014. Their results were published in November in Science Advances. It reveals that the Congo Basin lost around 165,000 square kilometers of forest during their study period.

In other words, one of the world’s largest rainforests lost an area of forest bigger than Bangladesh in the span of 15 years.

But why? Is it due to industrial pressure like in South America and Southeast Asia where the majority of deforestation has been done for soy, palm oil, and other commodity crops? Or commercial logging, which is razing forests on the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea?

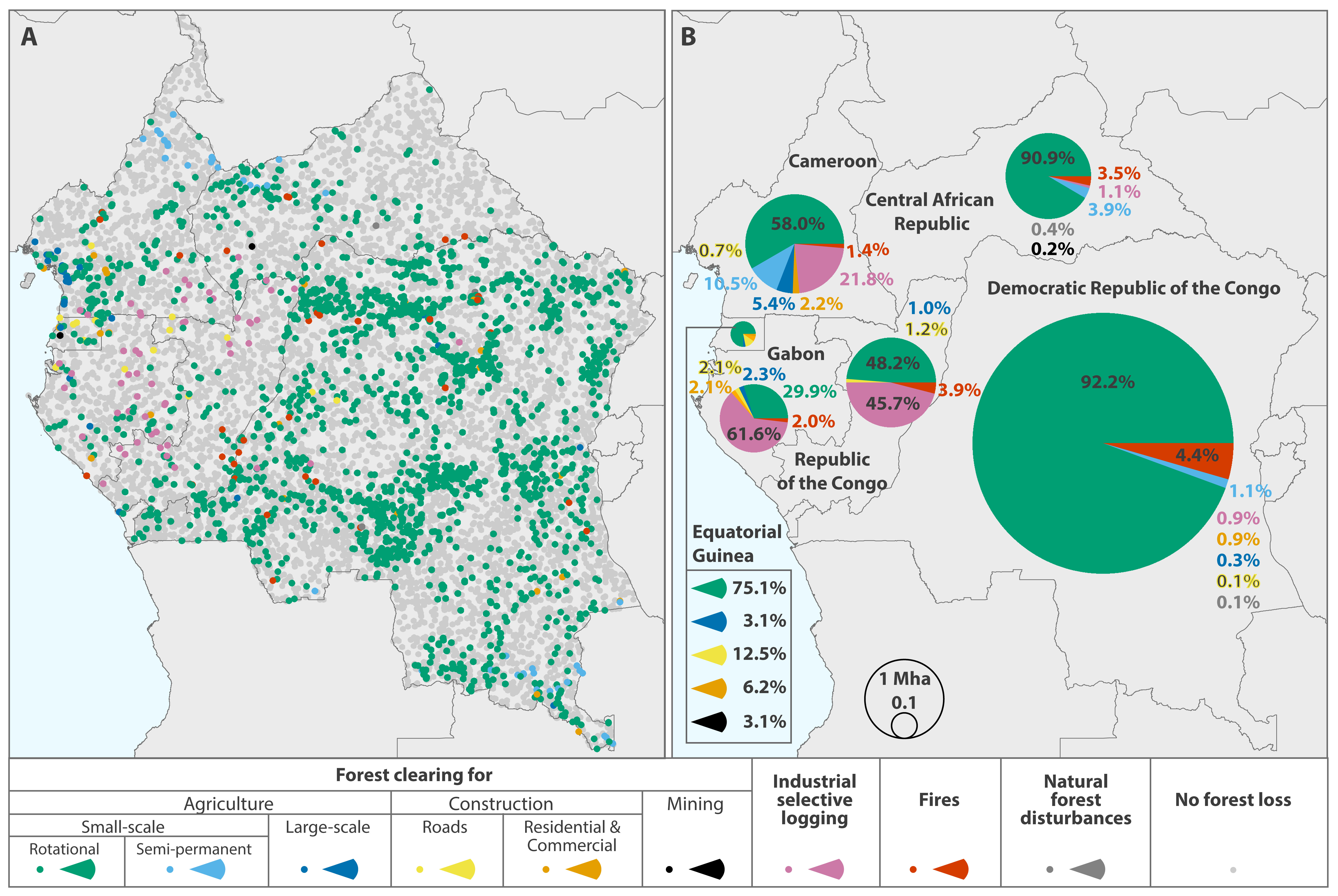

Not so much, according to this newest study. It reveals that the dominant force behind rising Congo deforestation, driving more than 80 percent of the region’s total forest loss, is actually small-scale clearing for subsistence agriculture. The researchers write that most of it is done by hand with simple axes.

According to the authors, the preponderance of small-scale deforestation of Congo rainforest is due largely to poverty stemming from political instability and conflict in the region. The Congo Basin rainforest is shared by six countries: Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, the Republic of the Congo, and Gabon. Of these, the DRC holds the largest share of Congo forest—60 percent—and is home to more people than the other five combined. The DRC, along with CAR, has a human development index in the bottom 10 percent, meaning that lifespans, education levels, and per capita gross domestic product there are among the lowest in the world.

With few livelihood options, most people survive by carving farmland out of the forest. These plots are farmed until the soil runs dry of nutrients, whereupon a new plot is cleared and planted.

Before now, it wasn’t exactly understood how much this type of smallholder farming called “shifting cultivation” and other forms of small-scale agriculture were contributing to overall Congo deforestation. So UMD researchers looked for patterns signaling different types of deforestation in regional tree cover loss data captured by satellites.

According to study co-author Alexandra Tyukavina, “it was important for us to explicitly quantify proportions of different drivers, to demonstrate just how dominant the small-scale clearing of forests for shifting cultivation is within the region, and to show that it’s not only re-clearing of secondary forests, but also expansion into primary forests.” Tyukavina is a post-doctoral associate at UMD’s Department of Geographical Sciences.

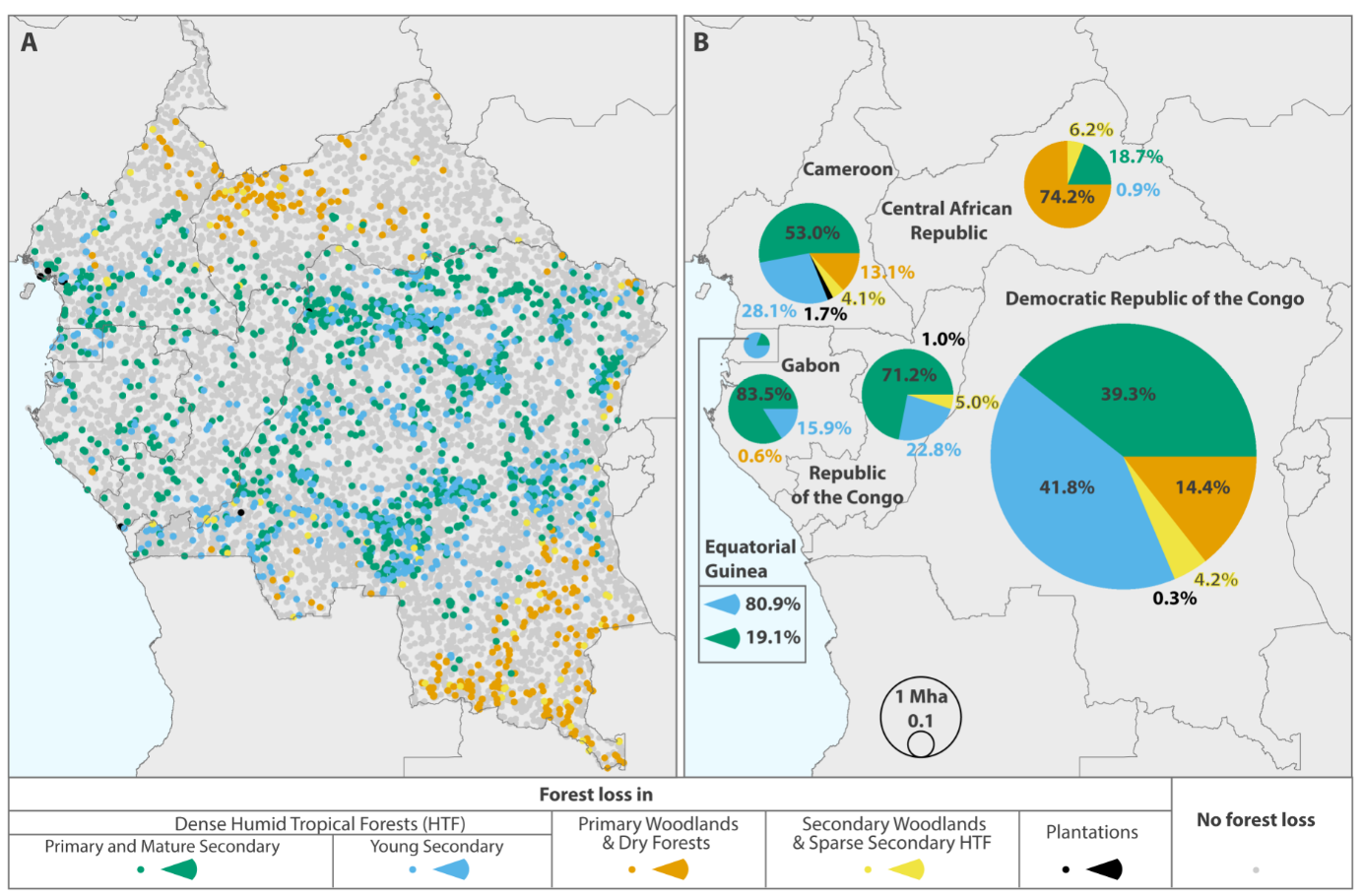

Tyukavina and her colleagues found that small-scale forest clearing for agriculture contributed to around 84 percent of Congo Basin deforestation between 2000 and 2014. When zooming in on the portions contained only in the DRC and CAR, that number goes up to more than 90 percent. The only country where small-scale agriculture isn’t the driving force of deforestation is Gabon, where industrial selective logging is the biggest single cause of forest loss.

The study also reveals that the majority—60 percent—of Congo deforestation between 2000 and 2014 happened in primary forests and woodlands, and in mature secondary forests.

The United Nations projects that there will be a fivefold increase in human population in the Congo Basin by the end of the century. The researchers found that, if current trends hold, this means that there will be no primary Congo rainforest left by 2100.

In their study, the researchers also warn of “a new wave” of large-scale clearing for industrial agriculture. While contributing a comparatively scant 1 percent of Congo deforestation during the study period, it appears to be trending upward, particularly in coastal countries.

“Land use planning that minimizes the conversion of natural forest cover for agro-industry will serve to mitigate this nascent and growing threat to primary forests,” the researchers write.

This story originally appeared at the website of global conservation news service Mongabay.com. Get updates on their stories delivered to your inbox, or follow @Mongabay on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.