In January 2002, a man who called himself Papa Pilgrim arrived in McCarthy, Alaska, with his wife, Mama Country Rose, and their 15 children. McCarthy is a small, end-of-the-road ghost town, a relic of a copper mining boom—fortunes were made and lost there in the first decades of the 20th century, but these days McCarthy is a quiet spot with just a few dozen year-round residents, surrounded on all sides by Wrangell-St. Elias National Park.

The family settled on an old mine site not far outside of town, a parcel of land whose owner had refused to sell out to the National Park Service but was more amenable to an old-fashioned homesteading clan like the Pilgrims. Alaska’s national parks legislation allowed for people to live off-grid in pockets of privately held land within the larger preserves, but it didn’t allow for what Papa Pilgrim did next: bulldoze a road across 13 miles of federal land. Within months, he was locked in a legal battle with the NPS. Soon enough, the stress of that battle would expose Pilgrim’s past and reveal the family’s dark, violent secrets.

“The challenge is how to bend civilization around wild nature, instead of the opposite, which is how we usually handle things.”

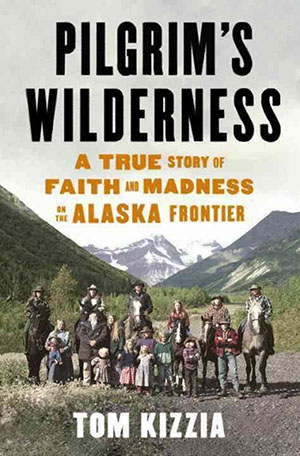

The story of Papa Pilgrim is told in a new book by journalist Tom Kizzia, who covered the saga as it unfolded for the Anchorage Daily News. Pilgrim’s Wilderness: A True Story of Faith and Madness on the Alaska Frontier is a gripping, fascinating, and sometimes horrifying read, powerfully written and disturbing. I contacted Kizzia to ask him about Pilgrim and the lure of off-grid wilderness living.

Early on in the book you write: “Many visitors fantasized about making McCarthy home. Few took the next step, and fewer still lasted through one winter.” I could relate—I’ve visited McCarthy and imagined myself staying. Why do you think so many of us are inclined to dream about such a harsh, isolated life?

The daily, elemental things you have to do to take care of yourself when you’re living in the remote, living the cabin life—the logistics of moving supplies, the self-sufficiency, dealing with problems that arise without calling a repairman, the hour-to-hour process of feeding the woodstove and hauling water—seem like an antidote to the urban feet-off-the-ground pace. The visitor may pause to think about how the help of friends and neighbors, and the close presence of nature, could fill life in satisfying ways. The more remote and challenging, the grander the achievement and satisfaction. It’s a pleasant fantasy, one that comes straight out of a readily familiar pioneer history. The Pilgrims really seemed to be committed to such a life, so that even the liberal-minded college-age idealists in McCarthy were impressed at first.

One of the fascinating things about the conflict between the National Park Service and the Pilgrim family is that, for many people, the NPS represents a connection to the wilderness and an opportunity to escape their contemporary urban lives, even if just for a day or a weekend. But to the Pilgrims and their supporters, the bureaucrats were a threat. Do you think that’s a resolvable tension, or will there always be conflict between government-preserved wilderness and the people most likely to want to immerse themselves in the wild?

The act of Congress that created Alaska’s parks hoped to resolve the tension, but in a way the law just brings it to the fore. How can wilderness be lived in and unspoiled both? It may be that when statutory Wilderness is protected for visitors, another kind of wilderness disappears, the free country that once beckoned the settler, or even the dreamer who might want to move into an abandoned cabin for a winter to have a go at survival. Meanwhile, bureaucrats have their careers and their fiefdoms to worry about, and that can create conflict with their neighbors. The people who live in McCarthy have thought a lot about this. The challenge is how to bend civilization around wild nature, instead of the opposite, which is how we usually handle things.

Do you think that Papa Pilgrim truly believed in the lifestyle he espoused—homesteading, self-reliance, simplicity—or was it largely a convenient way for him to isolate and control his family? Is it possible to separate the two motives in this case?

Tough question. The fact that no one could ever really be sure was part of what made the story so intriguing. I think he believed in that lifestyle because he was good at it. It was too hard to go so deeply into that way of living without total commitment. But where did that commitment itself come from? Papa Pilgrim had his children convinced that it was the voice of God. In their isolation, it was hard for them to disagree.

Do you keep in touch with the Pilgrim children? Are they still living relatively unconventional lives, or have some of them “opted in” more fully to modern society?

I’m a little bit in touch. They don’t live deep in the wilderness any more. They live in a rural/suburban part of Alaska, an hour’s drive from Anchorage. Their homes are comfortable, with plumbing and carpets, and they find ways to make a living in the wider world. But there is still a fundamental apartness to their lives that comes from their whole-hearted religious beliefs. It gives them a little edge to question things that go unchallenged in many American lives. Hunting, gardening, and self-sufficiency all still contribute to their standing a little apart.

We’re telling stories all week about people who opt out of society on some level—homesteaders, back-to-the-landers, anti-government survivalists. Read the entire series here.