We all know about the resurgence in knitting, and the rise of the backyard chicken coop, and chances are you’ve heard about the renewed craze for canning, pickling, and preserving, too. Some call it homesteading; some call it an overly precious affectation. But what does it all mean?

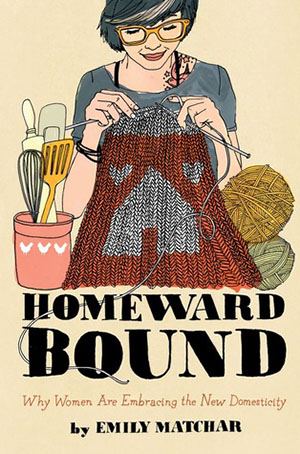

In a recent book, Homeward Bound: Why Women Are Embracing the New Domesticity, author Emily Matchar tackles the underpinnings of the trend—in this case, of young women, specifically, returning to the traditional skills and crafts of their grandmothers. In the book, Matchar argues that the shift has its roots in the disaffection of a youthful middle class; she also assesses its implications for gender roles and dynamics. I contacted Matchar to ask her what she makes of the trend.

The people who are most interested in pursuing these kinds of slowed-down, more home-focused lifestyles are educated middle-class people.

How did you get interested in the various linked phenomena that you’ve collectively dubbed “the New Domesticity”? Were you a participant in the trend, or was it largely something you observed in others?

I had always liked to cook and craft, and harbored a then-unusual-for-a-20-something fascination with Martha Stewart. So I watched with interest as I noticed more and more people my age become incredibly domestic over the past five-10 years. I had never quite understood my own fascination with traditional home skills, so I was curious to see why others were pursuing the same interests at an even higher level and with such intensity.

I was raised by hippie parents who are always happy to remind me that they were eating bulgur and supporting local farms long before I was born—their feeling is that these “new” DIY and foodie trends aren’t really all that new. Do you see modern twists in the ways people are reviving these skills?

As your parents point out, there are a lot of parallels between New Domesticity and the back-to-the-land movement of the 1960s and ’70s. I think the New Domesticity is less countercultural—most of the people I talked to were doing their cooking, crafting and chicken-keeping in normal urban or suburban homes—and relies more on technology—it wouldn’t exist without blogs!

You’ve observed that the New Domesticity is predominantly a middle-class phenomenon. Are there economic forces driving this shift?

The people who are most interested in pursuing these kinds of slowed-down, more home-focused lifestyles are educated middle-class people. They have the education and enough money to even consider spending their free time growing vegetables (as opposed to having to work double shifts cleaning office buildings, say), but don’t have enough money to simply buy their way out of the problems of modern life—hiring nannies, buying all of their expensive organic veggies at Whole Foods. They have the education level to have high expectations for job satisfaction, yet are likely to have mid-level, unsatisfying jobs (as opposed to the high-powered, high-status jobs of the truly rich).

Homeward Boundfocuses mainly on women and the revival of traditionally female tasks like canning and preserving. Do you think there’s a parallel trend for men, too—say, a revival of carpentry or subsistence hunting, that sort of thing?

Definitely. And although my book looks at the New Domesticity phenomenon through a women’s issues lens, I also interviewed a number of men who are interested in similar or parallel things. Some also loved to bake and knit, while others were doing carpentry or hunting or home-brewing (as were some of the women). But I do think this is a largely female-led movement, and I hope more men will become involved. Unfortunately, there’s still a lot of prejudice against men who pursue so-called “women’s work.”

This might be a hard one to parse, but how much of the New Domesticity do you think is driven by suspicion or concern about mainstream commercial options—Big Ag, for instance—and how much is about pure personal fulfillment and enjoyment?

I think New Domesticity is driven both by suspicion of government and institutions—Big Agriculture, the FDA, Walmart—and the genuine desire to live a slower, more satisfying life. Some people were driven more by suspicion (they’d seen Food Inc., for example, and it totally shook their world), while others were initially more motivated by their love for crafty domestic hobbies and the political feelings followed. So it depends on the individual which motivation is greater.

We’re telling stories all week about people who opt out of society on some level—homesteaders, back-to-the-landers, anti-government survivalists. Read the entire series here.