Would you like your tofu, soy crackers, and edamame to be rich in fiber, or would you prefer the foods to be infused with the herbicide Roundup?

If you would opt for the former, then recent research suggests you should eat organic—and avoid GMO soy. If your preference is for the latter, you’re risking little-understood health problems. And you’re quite possibly in the employ of Monsanto’s PR department.

More than 90 percent of America’s vast soybean crop is genetically modified. Most of it was engineered by Monsanto to withstand the herbicide glyphosate, which is the main ingredient in Monsanto’s Roundup weedkiller. The upshot of the technology is that farm workers can blast a field with Roundup and kill the weeds—while leaving the crop still standing. The downside is that it means blasting food and rhizosphere microbes with poison.

The specific health effects of pesticides are vociferously disputed, but they are known to be toxic to human cells, and they have been linked to hormonal and reproductive problems.

A team of Norwegian researchers sampled three-kilogram batches of market-ready soybeans grown in 31 Iowan plots. A third of the batches had been grown from Roundup Ready seeds. Of the non-GMO varieties, 10 were grown using pesticides, and 11 were grown organically. The scientists tested the samples for concentrations of protein, fat, nutrients, trace elements, and pesticide residues.

They concluded that the organic soy had the most healthy nutritional profile.

The organic soybeans had “significantly higher” levels of protein than the crops that were grown using chemicals, and they had lower levels of fatty acids that have been linked to obesity, the researchers wrote in a paper in the journal Food Chemistry. And the non-GMO varieties also had “superior nutrient and dry matter composition” compared with the GMO strains, regardless of how they were grown.

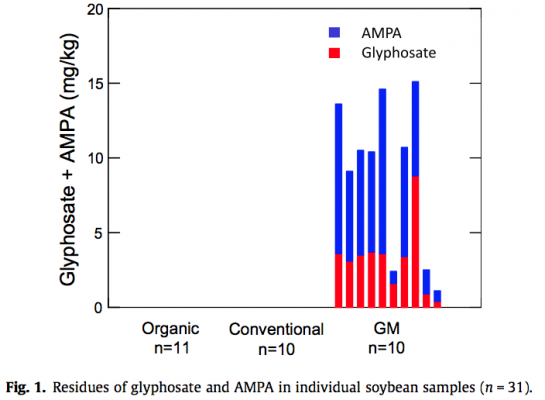

The discovery that could really cause you to blow your lactose-free GM soy milk out of your nose, though, was related to pesticide residue. The scientists found high concentrations of glyphosate and AMPA, which is formed as glyphosate breaks down, in the genetically modified harvests—in concentrations they say were as high as some vitamins.

“I knew GM plants take up glyphosate when sprayed, and that it might be present in the beans,” says study co-author Thomas Bøhn, a GenØk scientist and professor of gene ecology. “However, that the amounts were as high as we document—on average, nine milligrams per kilogram—was a surprise to me. It likely reflects that the farmers spray several times during the growth season, and also relatively close to the harvest.”

The specific health effects of such pesticides are vociferously disputed, but they are known to be toxic to human cells, and they have been linked to hormonal and reproductive problems.

The paper was posted online in December ahead of printing this June. It has been receiving a flurry of attention following a provocative essay written by Bøhn and another study author, published last week by Independent Science News, which argues that governments are unsafely raising limits on pesticide residue—”not based on new scientific evidence,” but to help GMO soy products stay legal.