When the Mississippi burst its banks earlier this month, the flooding was at once unusual and all too familiar. The river doesn’t normally flood in winter (with snowmelt and seasonal showers, spring’s the soggy time of year), but torrential December rains raised it to record-breaking heights. In Thebes, Illinois, floodwaters crested at 47.74 feet, the town experiencing a 200-year flood.

What sounds like a freak occurrence probably feels more like déjà vu to residents along the Mississippi, where communities have recently been inundated with more and more so-called 10-, 25-, 50-, and 100-year floods. It’d be easy to think a “200-year flood” was little more than media hyperbole. In reality, though, these dramatic-sounding designations are based on real calculations, made by government agencies like the Army Corps of Engineers and Federal Emergency Management Agency. What’s worrisome is that these estimates no longer seem to reflect our increasingly waterlogged reality.

To understand why these stats, known as flood recurrence intervals, appear increasingly flawed, it helps to understand what they are. Despite what it sounds like, a “100-year flood,” isn’t necessarily something that occurs once every 100 years. Rather, it’s a flood of a certain size that has a one percent chance of happening in any given year. Just as there’s a one-in-six chance of landing a six when you roll a die, each year there’s a one-in-100 chance of a 100-year flood. And just as you can land a six more than once every six rolls, it’s also perfectly possible for a 100-year flood to hit more than once in a century—or in a single year, for that matter.

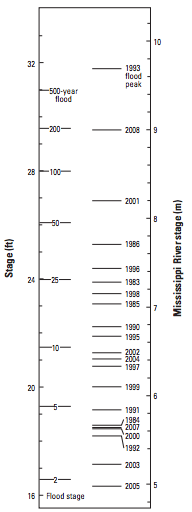

The thing is, these flood events, which should be relatively rare, are happening too often for the calculations they’re based on to hold water. Robert Criss, a hydrologist at Washington University in St. Louis, analyzed flood levels in Hannibal, Missouri, from 1983 to 2008 and found that, within those 25 years, the city experienced a 500-year flood, a 200-year flood, a 50- to 100-year flood, two 25- to 50-year floods, and five 10- to 25-year floods. He concluded that Hannibal’s official 100-year flood level was actually surpassed more like once every 10 years. In a more recent analysis of sites along the Mississippi, Criss discovered current estimates for 100-year floods were generally too low by three to six feet.

“If we assume that the 100-year flood has a certain elevation, when in fact it’s five feet higher, that means the so-called 100-year flood is much more likely to occur than we’ve determined,” says Rob Moore, head of the Natural Resources Defense Council’s water and climate team.

So, why are our flood-risk calculations so off? One reason is that they’re based on historical data that show how a river behaved in the past at a particular spot, but doesn’t factor in current or future environmental changes. “This is an acceptable strategy if and only if flood risk tomorrow can be correctly assumed to be pretty similar to previous years,” Moore says. “Climate change renders that assumption null and void.”

In the case of the Midwest, climate change is a growing factor in shifting precipitation patterns. According to the Third National Climate Assessment, the heartland has warmed 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit since the late 1800s, and some areas of it saw up to 20 percent more precipitation during that same period. The upward trend in moisture is expected to continue, too, with the heaviest downpours getting heavier—meaning that, when it rains, it will pour, and when it pours, it will likely flood.

Global warming isn’t the only factor boosting floods in the Midwest, though. Changes in water management and land use also play a huge role. So many levees, dikes, dams, and locks have been stuck in and along the Mississippi to control its flow that it’s no longer the river it once was. With more man-made structures in the mix, the only direction water can go when there’s a deluge is up. “This is not a normal response for a huge, continental-scale river,” Criss says of the recent flooding.

A lot rides on the accuracy of estimated flood recurrence intervals. FEMA uses these statistics to delineate 100-year flood zones on its maps, which the National Flood Insurance Program then uses to calculate rates for property owners. All sorts of structures, including levees designed to protect nearby communities, are built only high enough to withstand 100-year floods—heights that are apt to be surpassed more often than current estimates would suggest.

Flawed data can lead people to build—and re-build—in harm’s way, the costs of which are huge both in economic terms and, sadly, in human life. Between 1998 and 2014, FEMA spent a whopping $48.6 billion repairing damage from major floods, and the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research estimates more than 100 people die each year in the United States from flooding. The recent Mississippi flood killed at least 24 people in Illinois and Missouri.

As these risks become harder to ignore, they are spurring adjustments at the national level. In January 2015, President Obama signed an executive order requiring federal agencies to meet more stringent standards when building in floodplains. As of last March, FEMA now requires states to consider the effects of climate change in their hazard mitigation plans. And in light of recent floods, the Army Corps of Engineers is seeking funds to update its flood frequency intervals for portions of the Mississippi River (the last update was completed in 2004). This time, it plans to work with climate experts to figure out how best to incorporate climate change into the analysis, says Rene Poche, a public affairs specialist with the Corps.

To better understand the capability of future floods, we need to better understand the current ones. “We make decisions as if we know how high a 100-year flood will go, even though the evidence shows that we do not,” Moore says. “We have to recognize that our understanding of flood risk is, at best, faulty.” The first step to any solution is admitting there’s a problem. The second is doing something about it.

This story originally appeared on Earthwire as “Raising the High-Water Mark” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.