The barrier reef that runs along Australia’s tropical northeast isn’t just beautiful—it’s a lifesaver. Like other coral reefs, the Great Barrier Reef buffers waves whipped up by tropical storms, acting as an aesthetically stunning breakwater that reduces shoreline erosion and protects waterfront neighborhoods and ecosystems from floods.

But coral’s protective relationship with humans can’t be a one-way sea lane.

While one recent paper demonstrated the importance of protecting healthy reefs amid climate change, another has revealed that restricting fishing might be an effective way to save the corals that protect us.

After analyzing 27 scientific studies, researchers noted earlier this month that coral reefs reduce wave energy by an average of 97 percent, absorbing even more as wave energy levels rise.

After analyzing 27 scientific studies, researchers noted earlier this month in a Nature Communications paper that coral reefs reduce wave energy by an average of 97 percent, absorbing even more as wave energy levels rise. The American, Canadian, and Italian scientists found that by absorbing this energy, coral reefs help to protect more than 100 million people worldwide from rising seas and natural disasters—most of them living close to Pacific Ocean shorelines.

But as the warming globe is subjected to more damaging tempests, the coral reefs that so many coastal dwellers depend upon are dying. “Reefs face growing threats,” the team writes, pointing out that restoring a length of reef comes at a cost that’s less than one-tenth of the price tag for constructing an equivalent stretch of breakwater.

And in a new paper published last week in Global Change Biology, an Australian team of researchers offers clues about how these reefs can be protected.

In early 2011, Australia’s east coast was hammered by heavy storms and flooding. The deluges were so heavy that sea levels temporarily dropped worldwide. As the rainfall flushed back out to sea, it carried mud, sand, and other sediment with it. The Brisbane River flushed the equivalent of 20 years’ worth of sediment flow into Moreton Bay, where coral reefs support diverse fish populations

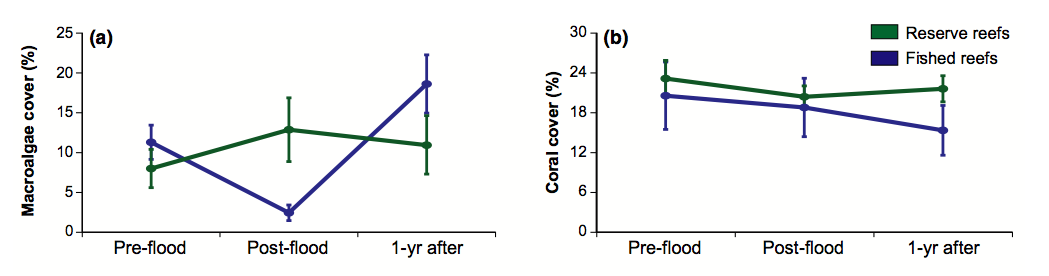

The scientists compared how 10 patches of coral reefs in Moreton Bay, which is just south of the Great Barrier Reef, recovered after the sediment deluges. Using data obtained before and after 2011, they found that all four studied reefs in marine reserves recovered within a year of the floods. None of the six reefs outside the marine reserves recovered during that time.

That’s because fish graze on algae that grow among coral, helping eliminate the reef’s main competitors.

Check it out:

(Chart: Global Change Biology)

Andrew Olds, a research fellow at the University of the Sunshine Coast who co-authored the paper, says the findings “provide a glimmer of hope” for coral reefs everywhere—not just for the great barrier variety.

“Reefs outside our study area that are in marine reserves may very well cope better with floods,” Olds says. “This would, of course, depend on why and how reserves were implemented, and how well they’re managed.”