Every time the winds blow east from the deserts of the Southwest, it means less water for 27 million people who depend on the Colorado River.

Layers of dust form every year on snowfields in the Rocky Mountains, blown in from pastures, farms, dirt roads and off-road vehicle parks. For decades, according to a study released this week by the National Academy of Sciences, this dust on snow both accelerates the annual runoff by weeks and reduces what reaches the Colorado River by 5 percent.

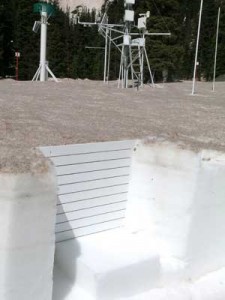

Clean snow reflects about 80 percent of the sunlight that hits it. But in the high Rockies, dust on snow absorbs heat from the sun, dropping reflectivity to just 33 percent, said Thomas Painter, the lead researcher for the study and a snow hydrologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“The dust is doubling the load of sun going into the snow pack,” Painter said. “It’s so effective at melting down the clean snow underneath it and on top of it.”

The dust, which looks like dirt, can fool the eye, too.

“It can look like a desert,” Painter said. “It really looks like you’re skiing on sand dunes. It’s stunning. At times, we would get a little confused.”

In all, the scientists found, 35 billion cubic feet of Colorado River runoff — Los Angeles’s water use every 18 months — is lost each year because of dust on snow. They estimate that the loss goes back 80 years. While this is bad for humans, 75-year-old rules on using the open range have helped; today, there is five times as much dust on snow in the Rockies as in the mid-1800s, down from six times as much at the turn of the 20th century.

Previously, Painter co-authored a study of mud cores from mountain lakes showing that dust in the Rockies increased six-fold between the mid-1800s and the early 20th century, as settlers trooped into the Southwest with their livestock and plows. The cattle and the farmers disturbed the delicate desert crust and left it vulnerable to blowing in the wind.

The new study is the first to quantify the effects of dust on snow on the scale of an entire river basin. It shows, too, that dust is far more damaging to runoff than the soot that blows into the Rockies from coal-fired power plants in the region.

Steven Fassnacht, a Colorado State University snow hydrologist who has studied dust on snow in Spain and Antarctica as well as the American West, called the findings of Painter’s team “ground-breaking and important.” Although the study did not look at how dust changes the surface of snow (it makes it smoother), these effects would not likely change the overall conclusions, Fassnacht said. The team’s methodology “should be applicable anywhere in the world,” he said.

Experiments on the rate of snowmelt date back to Ben Franklin, the American statesman better known for kites and keys. He placed pieces of colored fabric on snow, and he found that the snow melted fastest under the darkest cloths.

Because it is dark, dust on snow causes more snow to evaporate, and faster. (A similar concern about soot from oceangoing vessels concerns those watching Arctic ice decline.)

Specifically, the snow pack in the Rockies melts three weeks earlier than it did decades ago, Painter and his colleagues found. The earlier melt exposes the underlying plants, which then draw up water and exhale it into the atmosphere. Three more weeks of that plant activity accounts for most of the runoff loss.

Jeff Dozier, a snow hydrologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who reviewed the NASA-led paper for publication, said the highlight of the report was that three-week calculation for earlier snow melt.

“This is a real advance,” he said. “That’s probably occurring in other places of the world.”

For the study, a team of six scientists from NASA, the U.S. Geological Survey, the National Snow and Ice Data Center of Boulder, Colo., the Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies of Silverton, Colo., and the University of Washington collected snow samples at various levels. They measured the reflectivity of the snow and the balance of energy coming in and going out. They used advanced hydrology models, and they compared the present to the past.

The Colorado River supplies water to seven states — Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming — and the supply is already overcommitted. Compounding the problems for water managers, the snow is melting more often in the spring, not in the summer, when farms and cities need it the most.

Over the years, drought, wildfire, off-road vehicle parks and dirt roads for oil and gas exploration, in addition to grazing and farming, have contributed to the layers of dust on Rocky Mountain snowfields, the scientists said. Unless steps are taken to curb the dust and help prolong snow cover, they said, more runoff could be lost as the region gets drier. Up to 20 percent of Colorado River flow could be lost by 2050 because of climate change, scientists say.

Compared to the challenge of high-level international negotiations over greenhouse gas emissions, the study said, dealing with man-made disturbances in the Southwest high desert would be a relatively easy way to cushion water shortages from the Colorado River.

It’s been shown before that regulation (as well as progressive grazing practices) can help keep the dust down. The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934, which required permits for grazing on public lands, effectively reduced the amount of dust falling in the Rockies by 25 percent.