What do the fates of the tiny Pacific island nations of Tuvalu, Tonga, Kiribati and the Russian launch of a gleaming new European gravity satellite have in common?

Gravity itself.

Variations in Earth’s gravity field — which is a reflection of how Earth’s mass is distributed around the planet — is as subject to the constant motions of the world’s oceans as it is from massive mountain chains. And in how those seas slosh around the globe lies the fate of some 600 million people living in low-lying nations and coastal areas around the world.

Their futures are linked inextricably to gravity-field data to be gathered by the European Space Agency’s upcoming GOCE mission.

GOCE, the space agency’s one-ton Gravity field and steady-state Ocean Circulation Explorer launched today from Plesetsk in Northern Russia, is the first installment of the agency’s Living Planet Program.

Over some 18 months of its nominal mission, the 340-million-euro ($430 million) satellite will measure the variations of Earth’s gravity field, while doing its best to avoid disturbances caused by traces of Earth’s outer atmosphere.

But GOCE needs to be as close to Earth as possible in order to detect miniscule variations in the planet’s gravity-field signals. That’s why it will use ion thrusters to keep it at a mean orbital altitude of some 260 kilometers, or a bit more than 160 miles. From there, GOCE will make unprecedentedly precise global gravity-field measurements.

Its data will, in turn, be used in conjunction with the ongoing U.S.-German Gravity Recovery And Climate Experiment, or GRACE, mission, which launched in 2002. Both GRACE and GOCE will give climatologists the best overall measurements of global sea level yet.

Previously, such satellites measured sea level locally but not globally. GOCE will achieve global measurements by which to calibrate the local measurements.

Unlike GRACE, GOCE doesn’t have the ability to measure changes in the gravity field over time. But its high resolution snapshots will enable researchers to use gravity field data with an accuracy of up to a centimeter and a resolution down to 100 kilometers.

Researchers will in turn use this data to gain a better understanding of current sea levels and global ocean circulation.

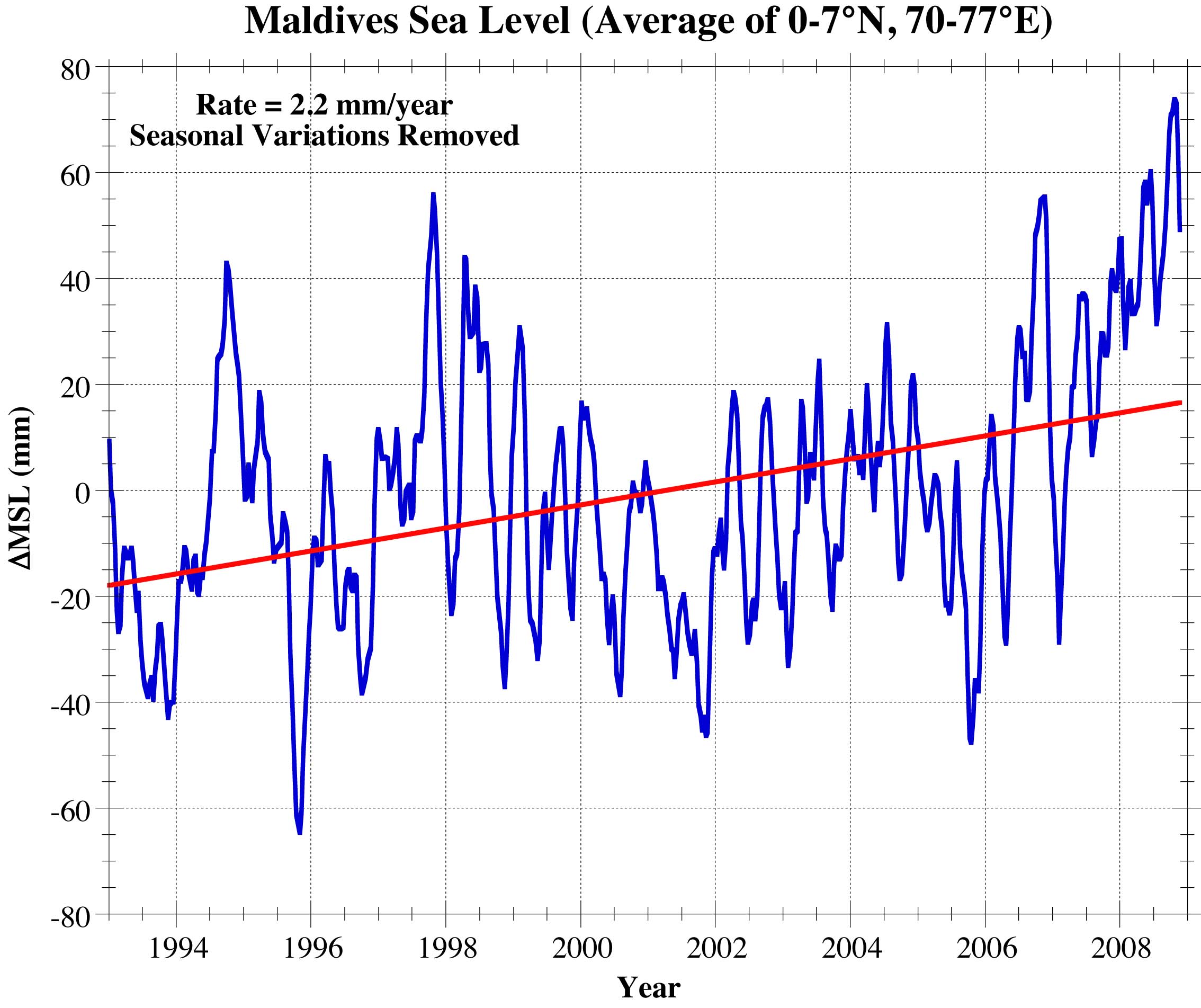

Sea-level rise is already happening, more or less, 10 times as fast now as it was a millenium years ago. Sea level has risen some 20 centimeters since 1880, and by 2100 could top a meter or more. Currently, global sea levels are thought to rise on average about 3 centimeters per decade, or about 1.2 inches. Some areas will rise faster; even now some areas will fall due to differences in ocean temperatures from one region to another.

Meanwhile, 20 percent of the Earth’s surface lies within 100 meters above and below the present mean sea level, including the Maldives islands, the Nile delta, parts of Bangladesh, Africa and Southeast Asia. If the rate of rise doubles or triples in the next couple of decades, these at-risk regions will be more likely to suffer flooding, storm surges, coastal damage or even complete inundation.

“Satellites have been making measurements of sea level the world over now since the early 1990s,” said ESA geophysicist Mark Drinkwater, GOCE’s mission scientist. “GOCE will provide a highly detailed map of the reference topography in any given location in the world. We can look at the sea-level change rate and say whether the sea level is going up and down locally.”

GOCE’s improved gravity-field knowledge will make the “slopes” of the sea level observable, said GOCE researcher Jakob Flury, a geodesist at Leibniz University in Hannover, Germany.

Such slopes are too small to be detected from the ocean surface itself. They range on the order of only a meter over hundreds of kilometers. But with GOCE, Flury said, these slopes can be observed with centimeter accuracies and therefore can provide a detailed picture of ocean-current patterns over scales of between hundreds and thousands of kilometers.

GOCE will give climate modelers a precise reference for global mean sea levels through the aid of its prime instrument, a gravity gradiometer; providing such measurements in all spatial directions.

As part of the gradiometer, six onboard accelerometers, operating in pairs spaced 50 centimeters apart, will measure differences in the pull in gravity, between small on-board test masses. These variations represent the signature of earthbound masses such as mountains, valleys, ocean ridges, ice packs, the oceans, as well as large masses from deep within Earth’s own interior.

“Six months after launch,” Drinkwater said, “we will be able to make a global map with a unique view of sea surface height variability. This will tell us how to link measurements of sea-level rise from one side of the Pacific to the other. It’s this height variability that drives ocean circulation. Understanding height variability is critical to improving models for more accurate forecasts of climate change.”

Where all this additional water in the rising seas originates is a subject of debate.

“We don’t really understand all the sources of melting,” said Steve Nerem, an earth scientist at the University of Colorado, Boulder. “A third of the sea-level rise is due to melting of mountain glaciers such as the rapidly melting Alaskan glaciers. A third is due to melting of Antartica and Greenland. And a third is due to thermal expansion caused by absorption of heat into the ocean.”

Researchers know that Greenland and Antarctica are both melting at about the same rate. While GOCE will be able to measure the shape of that ice, it still won’t be able to tell researchers how the ice is changing.

Such ice sheets are the most important in terms of possible catastrophic rises of more than a meter of sea level.

“If you melt ice in Greenland and it runs into the ocean, sea level goes up,” said Josh Willis, an oceanographer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “The ice that used to be on Greenland was actually pulling, or gravitationally attracting, the water that was in the ocean near its coast, so the water level next to the coast of Greenland will go down. That’s because the gravity field created by all that frozen water will have actually changed thanks to its disappearance.”

On larger scales, Willis says that ocean flows such as the Gulf Stream and the Antarctic Circumpolar current can also tilt the surface of the ocean in the direction of the prevailing gravity. As a result, GOCE should help oceanographers better understand global ocean circulation.

Willis believes the overriding issue is determining what will ultimately happen to the ice sheets. He notes the Greenland ice sheet and the West Antarctic ice sheet are both big masses of ice that remain over land masses. When these ice sheets’ melt-water runs into the oceans, sea level rises.

Much of the melting Arctic ice, by contrast, is already afloat and thus has no impact on sea-level rise.

“The atmosphere is warming; the ocean is warming; and the ice is already melting in both places,” Willis said. “Most climate scientists would suggest sea-level rises of 2 meters over the next 100 years. That would certainly wipe out Kiribati, whose highest level is 6.5 feet.” And as Willis points out, many Pacific island nations like Kiribati would have a problem with even a foot and a half of sea-level rise.

“GOCE will give us insight into contemporary sea-level change and its variability the world over,” said Drinkwater. “And it will provide a tool for making more educated decisions about how to plan for the future and how to mitigate the problem of sea-level rise for these low-lying nations.”

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.