In a few short years, ride-sharing companies have dominated their taxi competitors. In San Francisco alone, Uber reportedly earns more than three times the entire taxi market ($500 million vs. $140 million). Today, Uber’s main competitor, Lyft, announced that it has raised a whopping $500 million, at a $2.5 billion valuation.

Anyway you slice it, investors think that ride-sharing is going to be worth many times more than the entire cab industry. More importantly, new research from Uber’s data science team reveals why taxis may never be able to compete with their Silicon Valley rivals.

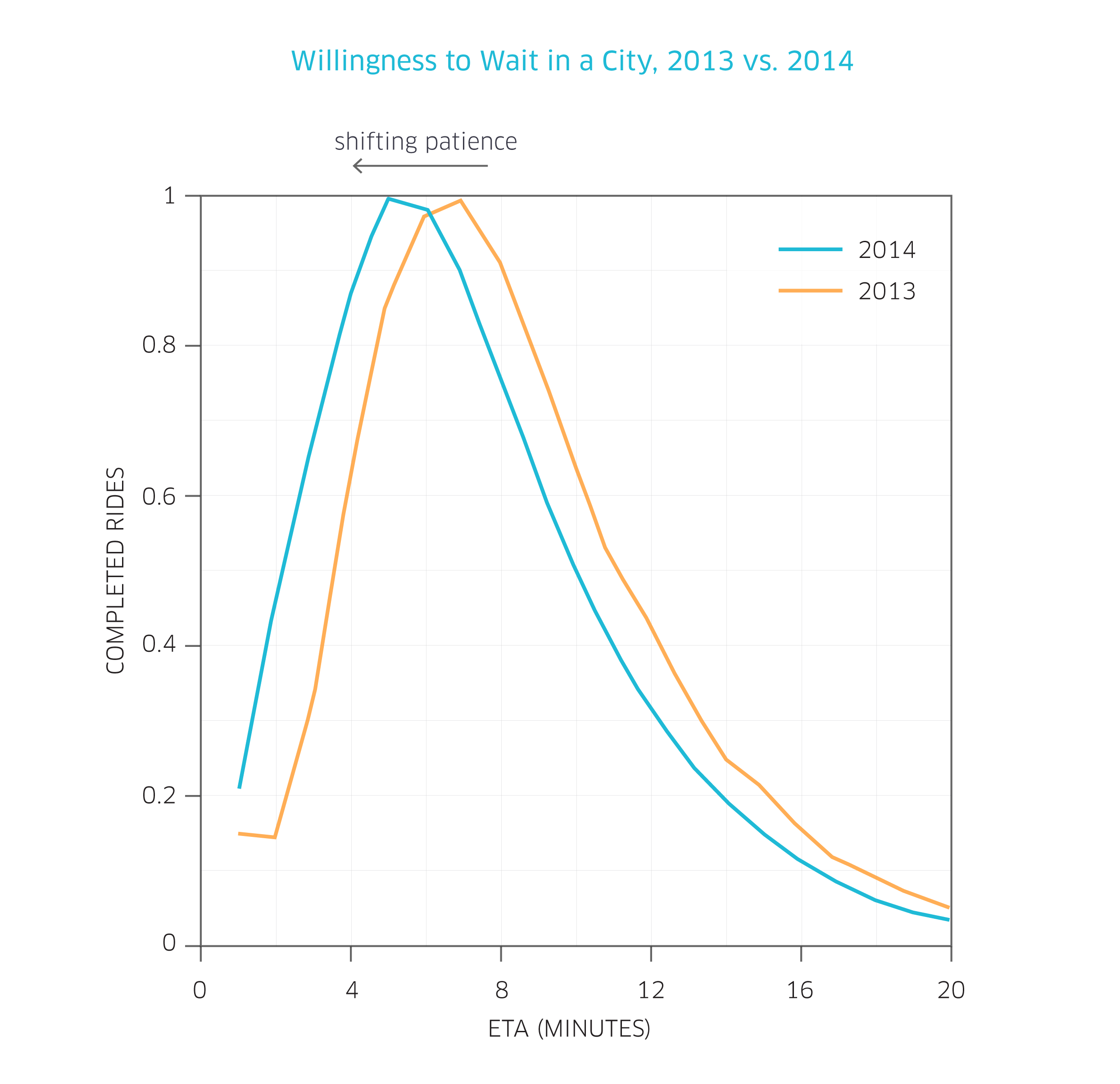

The longer Uber exists in a city, the less patient consumers become. “In some cities, if users see the nearest Uber is more than even 2-3 minutes away, they are far less likely to request a car, while in other cities wait times as long as 10 minutes are perfectly acceptable,” the team wrote.

In other words, Uber is making consumers impatient.

In San Francisco, one study found that just 16 percent of taxis arrived in less than 10 minutes after being called, while 90 percent of ride-sharing cars did. (To be sure, the taxi industry is suffering huge losses in San Francisco.) This is a structural problem with taxis. Unions purposefully limit the numbers of cars on the road to keep drivers’ wages artificially inflated.

Cab drivers often wait years for a medallion. They also have to pass a number of time-intensive exams. Given all the upfront costs, it’s harder to ask someone to be a cab driver. Uber drivers, on the other hand, can be certified in a fraction of the time, and work only a few hours a day. And no experience is required to learn insider tricks that might result in higher pay.

Uber alerts drivers to a potential surge in users, they hop on the road and are back home in a few hours.

Indeed, one study from Princeton economist Alan Krueger found that part-time Uber drivers earn the same as full-timers. “Uber’s driver-partners are essentially invariant to hours worked during the week,” Krueger wrote, which “makes Uber an attractive option to those who want to work part-time or intermittently, as other part-time or intermittent jobs in the labor market typically entail a wage penalty.”

In other words, Uber is the anti-union job: it trades wage predictability for hyper-flexibility. Consumers end up benefiting and dropping cabs like an antiquated computer.

Speaking personally, I used to be comfortable waiting 10 minutes or so for an Uber. Now, if its more than five minutes away, I cancel. I’ve come to expect immediate satisfaction. It is true that there are apps on the market that allow consumers to hail a unionized taxi, such as Flywheel in San Francisco.

Though it feels like Uber, in my experience, Flywheel takes longer during peak hours. They simply can’t put enough cars on the road to meet demand, especially when Uber and Lyft drivers can instantly go to work for just a few hours a day. Their flexibility is an inherent advantage.

The only way taxis could compete with Uber is to become like Uber. Either way, ride-sharing wins.