Twenty years after Junípero Serra left his home in Mallorca and traveled over 10,000 miles across sea and land and mountain, on foot and ship and mule, to the western edge of North America, he had an encounter with the indigenous people in a mythical place that the Spaniards called California. It would change his life and theirs forever. For all the tragedy that followed, roots of radical tolerance and mercy were planted that day that have surfaced dramatically, 250 years later, in opposition to a United States president.

On May 15th, 1769, Serra, the Franciscan friar, traveling north from Loreto in Baja to “discover” Alta California, happened upon his first non-missionized Indians “in their own country,” as he put it, ceding the notion that the land was not the Spaniards’ or anyone else’s but belonged to those who had been living there from time immemorial. This was a rather uncommon attitude for conquistadors, spiritual or otherwise. The people were the Cochimi, and the men were as naked, as Serra put it, “as Adam in the garden, before sin.”

Serra was astounded: “While they saw us clothed, not for a moment could you notice the least sign of shame in them for their own lack of dress.” Unlike most others on the expedition, who were repelled, Serra returned the Cochimi’s lack of shame with his own lack and not only did not judge them, he filled their hands with dried figs and put his hands on their heads in a blessing. Though some historians have accused Serra, unfairly I think, of being medieval (granted, whippings in the missions and other harsh punishments, however common for the times, were wrong), this was a moment worthy of Rousseau. (It is also notable that Serra never used the word barbaros in reference to the Indians of California.) The celebration of difference was quite different in its own right from the shunning of the minions of the devil most English Puritans acted out in response to Native Americans in New England and Virginia.

Being the son of a dirt farmer on an island that was plagued by famine and drought, Serra was impressed by the Cochimi’s ability to survive in the hostile, bone-dry landscape of central Baja. The unusual Cochimi habits of a “second harvest” of pitahaya cactus fruit that involved plucking the seeds from their own dried excrement to roast them for another meal—not to mention the practice of “maroma,” tying a piece of precious meat to a string and letting each person in a group swallow it just long enough to gain some sustenance before it was pulled out and given to another ’til it finally dissolved—must have struck him as extraordinarily industrious and selfless.

One can easily imagine that, on his epochal trek north in 1769, Serra viewed with similar wonder the fecund shameless beauty represented in the 250 caves of ancient rock art of central Baja, painted by the Cochimi and their ancestors (only discovered by anthropologists in the 1970s), eclipsing in their variety and expertise even the prehistoric caves of Lascaux, France.

When soldier depredations against native women began in Alta California, Serra sent for Cochimi couples from Baja—many of them mestizo—to serve as examples of “proper” sexual love. Soon he was giving incentives for intermarriage between Indian and Spaniard—two cows, a mule, land, and ultimately relief from military service.

A month after that naked moment with the Cochimi, on June 29th, 1769, Serra and Gaspar de Portola, commander of the expedition, came upon “good, sweet water” in a deep ravine just shy of San Diego. Portola wanted to water the thirsty horses and let the soldiers and muleskinners drink, bathe, and wash their clothes. But the Franciscan balked: “We did not allow it since they had already had enough to drink that day, and also because we did not want to contaminate in any way the watering place of these poor gentiles.”

Long before Henry David Thoreau or John Muir, Serra’s respect for the environment—and the indigenous peoples’ a priori right to it—was unlike just about any other colonizing power’s practice in the Americas, with the possible exception of Padre Kino in Arizona and the Jesuit reducciones in the rainforest of the Guaranis on the border of Argentina, Paraguay, and Brazil, memorialized in the great film The Mission. I know of nothing like such respect for that sweet water among the Puritans of New England, where our country is supposed to have been started. The Puritans generally wanted nothing to do with the Indians, despite the myth of Thanksgiving. They hadn’t come to the New World to mix, but to separate. The Spaniards mixed from the very beginning.

(Illustration: Eric Hinkley)

After two hundred years of conquest in Spanish America, half the population was still Indian, whereas east of the Mississippi River in English America, only 6 percent remained Indian. This does not dismiss the terrible damage wrought by germs, massacres in early Spanish conquest, and later the genocidal actions of the American cavalry (by 1870, California’s native population, spanning dozens of distinct cultural groups, had been reduced from 225,000 to only 30,000, an 87 percent drop). But the Spanish encounters on the West Coast were of a decidedly more accepting and less violent nature than those with the British in the East. As historian David Weber of Southern Methodist University wrote, “Throughout the Spanish-American mainland by the 1790s, numerous indigenous peoples had been incorporated rather than eliminated.”

Our country was started—or better started—in old California. And this moment of graceful tolerance and merciful respect for clean water seems to have occurred right in what is today’s Tijuana River National Estuarine Research Reserve, whose wetland straddles the modern-day U.S.-Mexico border. Serra mentions that day of forbearance taking place as they came across the Kumeyaay tribe’s rancheria “on a beautiful plateau that looks like an island.” That could very well be the thin peninsula carved today by the Tijuana River just south of Imperial Beach.

I have found, in retracing the birth of the State of California—and the social, political, and spiritual interactions of Spanish Franciscans with the indigenous population—fascinating roots of the state’s modern identity, clues to the source of the resistance that is brewing in California today to racism, despotism, corporate greed, a cavalier disregard for the importance of language, and environmental desecration. Besides the “sweet water” encounter, there were many other moments when both Serra and his confrere Father Juan Crespi spoke in awe of the beauty of California: the wild roses of Castile they spotted in the Los Angeles floodplain, Monterey Bay’s marvelous “thousands of sea lions seeming like a cobblestone pavement,” the stunning, fearful height of Big Sur ledges—the climb so painful and wondrous Crespi named Big Sur “The Wounds of Our Father,” in honor of St. Francis of Assisi’s stigmata on Italy’s Mount Alverna.

The reverence for nature and its power that the Native Californians possessed, and which was reflected in the Franciscans’ own worldview—have carried forward to this day. The reason Coast Route 1 along Big Sur is still breathtaking to visitors from all over the world is that former seminarian Governor Jerry Brown, in his first term in the 1970s, forbade coastal commercial development from Morro Bay to Carmel. It’s no surprise President Donald Trump, from the stone temples of Manhattan that long ago crowded out nature, cavalierly throws out protections for clean water, air, and coastlines sensitive to fossil-fuel spills. And it should also be no surprise Brown stands up for the environment against Trump, or even in lieu of him (as in November of 2017, when, after pledging California and many other states’ adherence to the Paris accords on global warming, European leaders addressed him as “President Brown”).

What effect might Junípero Serra’s radically merciful abstention from soiling the Kumeyaay’s “good, sweet water” have had on the tribe itself? Perhaps it influenced the tribe’s provisioning of food for the starving, scurvy-ridden Spaniards who came ashore in boats the natives thought were whales. The Kumeyaay were among the most resistant tribes to colonization in California; they were and are to this day a proud, strongly built people (the Campo Band of Kumeyaay were picked to represent the 500 California tribes in an exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian that ran from 2004 to 2015, one of eight North American tribes so chosen). When Serra forgave the Kumeyaay imprisoned for the killing of three Spaniards during the uprising of 1775 against Mission San Diego, springing 24 Indians from jail, they had to have been grateful. “As to the killer, let him live so that he can be saved, for that is the purpose of our coming here and its sole justification,” Serra wrote. When the rebel leaders became mission leaders afterward, it was radical mercy radically acknowledged.

The American poet William Carlos Williams said the job of poetry was to “reconcile the people and the stones.” The awe Junípero Serra experienced at the land and sea in aboriginal California and the respect he gave the Kumeyaay may be two parts of the same story. On the one hand, we have the fact that California contains the most national parks in the country, and the highest combined national park visitation of any state. On the other, we have Brown’s protection of “the stranger” in our midst, the millions of immigrants upon which the entire economy depends.

The state is a leader by many different metrics. California spends more per capita on justice and legal issues, including rehabilitation and gang intervention, than any state but Alaska ($381). Add to this the fact that California’s percentage of foreign-born residents is twice the national average (27 percent vs. 13 percent), and the Ninth Circuit Court in San Francisco’s rejection of the president’s attempt to shut off refugees from the Muslim world was nearly a foregone conclusion. Likewise, Trump’s levying of tariffs and attempts to cut down international trade pacts in the North American Free Trade Agreement did not find sympathy in the Golden State. (Long Beach and Los Angeles harbors alone handle about one-third of all U.S. container traffic.) In physical health and exercise, California is the No. 3 state behind Vermont and Colorado. Only Hawaii has a lower death rate than California; and California is among the lowest five states in infant mortality. According to Gallup, four of the 10 “happiest” cities in the country are in California. The Golden State also leads the nation in personal wealth, manufacturing, milk production, and agricultural crops.

Brown has sharply defended California as a sanctuary state for immigrants not just on moral grounds but economic ones, calling down the wrath of the Department of Justice, which in March of 2018 sued California. Brown’s reaction was unvarnished and equally angry, calling Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ lawsuit “a reign of terror” for attempting to force California policemen to cooperate with Immigration and Customs Enforcement in rounding up tens of thousands of Mexican immigrants who have had no violent criminal record and incarcerate or expel them over the border. Brown felt Washington was “basically going to war against the State of California.” In January of 2018, the state’s Public Policy Institute found that 65 percent of California voters support the protection of non-violent immigrants. With a culture that resists violence and respects women, California has one of the lowest rates of rape in the nation.

Of course, all is not perfect in the Land of the Sun. Anyone who has been caught in an L.A. or San Francisco traffic jam will not be surprised that those cities have the third and fifth worst traffic delays, respectively, in the nation (only Chicago and D.C. outdo L.A. in clogged roads). The California abortion rate is higher, and student reading proficiency and the state of weakening bridges are worse than the rest of the country. The state is not short on means to fix some of these things, however. California’s gross domestic product is the highest in the country at over $2.7 trillion (Texas is a distant second). And at 4.2 percent, the state unemployment rate is at an all-time low.

Disinclined to let the White House undo many years of progress, in May of 2018 California sued Scott Pruitt’s Environmental Protection Agency over retrograde standards on auto emissions. One year into the Trump presidency, California had sued the administration more than 20 times.

Throughout history, California has served as a sanctuary for outsiders seeking redemption, and the man who created the first ill-fated colony in the territory was no exception. By 1535, Hernán Cortés was something of a broken man. Many of his former associates in the conquest of Tenochtitlán had turned against him. He was mired in court battles, accused of profiteering hugely from the conquest of Mexico, not to mention out-and-out genocide by the Dominican priest Bartolome de las Casas. Removed as caudillo of Mexico, Cortés set sail across what would come to be called the Sea of Cortez, and on May 5th, 1535, he landed at today’s Malecón, the seaside boardwalk of what became La Paz, the capital of Baja California Sur. There he met Indians not easily “otherized” as the cannibal Mexica; they were the relatively peaceful southern Cochimi.

(Illustration: Eric Hinkley)

Cortés had been lured partly by reports of black pearls, but also a compulsion to start over. Terra incognita appeals to the humiliated, the proud brought low, but this one also drew Mexican settlers pulled by a westward horizon. Cortés was struck by a mythical place he had read about in a popular 1510 novel—the telenovelas of the age—written by an old Moor-slayer, Garci Ordonez de Montalvo, The Exploits of Esplandian. In that wild and wooly book, Montalvo invented the word California, for an island queendom led by an Amazonian black woman clad entirely in gold named Queen Calafia, who falls, naturally, for a Christian knight named Esplandian. Cortés found no Calafia, but a lot of cardon cactus and boojum trees, which he proceeded to slash with his sword to claim the territory. The local Cochimi were not impressed. Within a year, the first colony of Europeans in the Californias had pretty much disappeared; the few remnant settlers struggled back across the Sea of Cortez. Santa Cruz’s fate was not unlike that of the “Lost Colony” of Roanoke in Virginia a century later. California would see no further settlement for 200 years.

In April of 2017, I traveled to Baja with an old friend from childhood to try to find out what happened to Santa Cruz—or at least to locate it. This is, or was, not generally known in Mexico, and no book identifies the landing site exactly. There is no marker, no memorial. Cortés, I was told rather quickly, is hated in Mexico.

An elegant, tall archivist with a cane, Quintín Muñoz of the Museo Regional de Antropologia e Historia in La Paz, told me patiently, “The place has to be an old arroyo that was flowing with fresh water in spring of 1535—right here where the Calle 16 de septiembre goes into the Malecón in La Paz.” Quintin told me the lost colony of Santa Cruz was done in by thirst, “when that arroyo dried up in summer.” Water comes and goes fast in California. The colony was also sabotaged by an unnamed ship—pirates perhaps—who, famished, ate up the little food the colony had so fast that some of the interlopers’ stomachs literally burst.

My sailor captain friend was skeptical, because the Bay of La Paz is famously shallow and filled with sand bars. In fact, a 10-mile-long sandbar named El Mogote gives the harbor its exceptional protection, and this may have attracted Cortez. The Bay of La Paz swirls in what is known to boat people as the “La Paz Waltz,” turbulent water from the Gulf of California that builds up and tears down sandbars. Quintin saw no contradiction: “One of Cortez’s boats did scuttle on a sandbar. But he probably anchored beyond El Mogote when a search party spotted the fresh water.”

We inspected September 16 Street. No water flowing there now. Cafés. Nieve shops sporting mango sherbet. Rental cars requiring $40 a day for Mexican insurance. A museum. And in the Hotel Perla, a photograph of Elizabeth Taylor with a giant Baja pearl around her neck sparkling above her cleavage. Alas, her cat is said to have swallowed it just before she sued Richard Burton for divorce.

Though his colony failed, in picking the name for the new land of a mythical Queen surrounded by strong women, Cortés assured California a legacy of strong women, who, like Queen Calafia, might wield the ultimate mercy—love—to undo a former foe. Cortés bequeathed to his chimerical colony of California the very dreaminess he saw in that 1510 novel, a love of the art of story that became, centuries later, a culture of literature, art, and film. It would be a culture that invited the lost before they were found, with a keen sense of tragedy, as with all cultures dedicated to change—and change in the human heart.

“Trump lacks humility,” Governor Jerry Brown declared in a spirited 60 Minutes interview just before Christmas of 2017. “He has no fear of God.” Brown’s state was in the midst of being torched by wildfires among the worst in the country’s history, sapping the strength of over 8,000 firemen, the most ever gathered to fight flames. Together, the wildfires of 2017 in Santa Rosa and Southern California destroyed 10,000 homes and structures, torched 1.2 million acres, and killed at least 46 people. The subsequent mudslides in January of 2018, abetted by land denuded by the fires, killed another 23 souls in Santa Barbara, some of whom were plunged all the way down the mountain into the ocean. Nature will humble you, whether you pay attention to it or not.

“California is burning up,” Brown lamented. Perhaps behind the governor’s anguish—and his extraordinary rebuke of a president—was a cautionary tale for us all, and not just about global warming, but about the tinder that lies in growing poverty unaddressed. One of the smaller of the season’s fires, the Skirball, which destroyed multimillion-dollar homes in Bel Air, was started, probably inadvertently, by a homeless man living in the brush of a golden ravine adjacent to the 405 freeway.

(Illustration: Eric Hinkley)

The two-time governor of California whose four terms were separated by three decades of wandering and other service knows what humility is about. Brown gave up the habit on the road to being a priest, took a detour into a beautiful, rocky path called Linda Ronstadt, sang for his supper in two quixotic, losing tries at the American presidency, took a far less important but more demanding job of being mayor of industrial, multiethnic Oakland (hard to dodge constituents who are in your face if not honking at you on the highway). Tagged once by the label “Governor Moonbeam,” and now, after a highly successful fourth term that balanced California’s budget (from a $25 billion deficit in 2010 to a $7 to 10 billion surplus in 2018), shepherded the state into an economic powerhouse (the sixth largest economy in the world, if it were a nation), and achieved a sort of spiritual presidency of the environment and immigration, if not an actual one, Brown is staring down the tunnel of the end of his political career. Where is he retiring? Mar-a-Lago? Palm Springs? No. Williams, California—a one-horse town off Interstate 5 on the way to Oregon—where his ancestors found a modest plot of land on the approach to snow-capped Mt. Shasta.

How do you exert radical mercy? You have to have been broken yourself. You have to know what it means to need mercy in order to give it. Junípero Serra called himself “a fool” more than once and declared, “I am full of faults and perform badly in all things.” Compare this to Trump proclaiming, “I alone can fix it.”

Seventy-eight years before the Mayflower and 65 years before Jamestown, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, humbled if not humiliated by the bloodshed he witnessed of Cuban Indians, was the first European to make it to Alta California. In late September of 1542, Cabrillo discovered the “very good, protected port” of San Diego, calling it San Miguel, where the Kumeyaay “appeared to be very scared,” acting out violent people they called Guacamal on creatures like horses. “They indicated that they were afraid because the Spaniards were killing many Indians in the region,” Cabrillo later reported. (This was probably the marauding Coronado in Arizona and New Mexico.) The two peoples exchanged gifts, and though some shore Indian arrows wounded three of a search party of Cabrillo’s men in a dinghy, Cabrillo seemed sympathetic to the Kumeyaay’s plight—and the advantages of San Diego—noting that “a violent storm” had recently hit and frightened them, the first they had ever experienced, “but because this was a good port they did not suffer at all.”

Cabrillo’s hopes for redemption got plenty buffeted—by winds, lack of fresh water, scurvy. The Chumash of the central coast of California literally saved the lives of Cabrillo and his crew by provisioning them with fresh water and fish. After making it more than halfway up the coast, the expedition was forced by bad weather to turn south. They had found Monterey Bay, but missed San Francisco Bay, and ended up taking refuge once more with the Chumash on San Miguel Island (one of the Channel Islands off the coast of Santa Barbara), where Cabrillo appears to have fallen on rocks on shore or inland, breaking a leg, which became gangrenous. The closest doctor was 1,000 miles away in Guadalajara. He died, and was buried, though no one knows exactly where.

Some say Cabrillo was thrown overboard, buried at sea like a true sailor. A recent theory holds that, due to misidentification of islands called Posesión (as San Miguel was first called) and conflicting logs from Cabrillo’s three ships, Cabrillo actually is buried on Catalina Island. (This theory is supported by respected anthropologist John Johnson of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History.) All this is further complicated by the discovery of a Spanish sword hilt festooned with scallop shells on nearby Santa Rosa Island, along with what appears to be a small gravestone marked with a cross and the initials J.R., a third initial blurred. Yet there is no written evidence Cabrillo stopped on Santa Rosa Island. However, a marker for Cabrillo’s distinction of being among the first known Europeans dead on American soil (just after Hernando de Soto in Florida and Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca in Texas) was placed in 1937 on the remote San Miguel Island, where he certainly did anchor, and it is to there I flew, by grace of the U.S. Park Service, on April 11th, 2017.

We landed on a carpet of flowers and grass. It was a six-seater small plane chartered by the National Park Service, which was flying a ranger, Juliann, and a radar dish repairman to this most remote—and most northerly—of the eight Channel Islands. They squeezed me into the last seat. Alighting, the wind was all around and all around the sea. No one lives full-time on the Channel Islands—with the exception of the hoteliers of Catalina—though they once did. The Chumash had the largest, most dense population in Alta California on Santa Cruz Island. Today, the islands (with the exception of Catalina) are all owned either by the NPS or the Nature Conservancy. A hike on San Miguel with Juliann through horsetail, coreopsis, and blue lupine brought me to the obscure Cabrillo monument, a small cross with a curving base on top of a rock cairn covered by pale green and pepper black lichen with a dollop of bird shit. It is a place rarely visited, then or today. The marker reads: Joao Rodrigues Cabrillho, Portuguese Navigator. Discoverer of California 1542. Isle of Burial 1543. Cabrillo Civic Clubs, Jan. 3, 1937. Clearly, Portugal enthusiasts promulgated a now-discredited theory that Cabrillo was Portuguese. It’s more likely he was Spanish, from Seville and Cordoba in Andalusia.

Little San Miguel Island (it is eight miles long and at most four miles wide) is filled with solitude and defeat. Two veterans of war—the U.S. Civil War and World War I—thought they could escape their nightmares and society by bringing their young families to San Miguel in the 1880s and 1920s. Neither had much success, though sheepherding and shearing worked for a while. I came across the remnants of the last stand of the Lester family, a crumbled old chimney whose red bricks seem somehow alive, harboring inside nettles—a touch of old warmth. Nearby was a tossed-away stone sink and an iron bowl, both overgrown with nettles as well. Juliann pointed to what looked like Queen Anne’s Lace, except it was pink. “It’s pink yarrow, found nowhere else in the world,” she smiled.

In his haunting novel about isolation, San Miguel, T.C. Boyle evokes the plight of sheepherder Herbie Lester, the island’s last inhabitant, angry about the clouds of war growing in the ’30s coming closer to his island redoubt, the U.S. Navy knocking on his door to buy the place for defense against Japanese subs. Boyle muses about “how far out of the sphere of things you’d have to go, geographically and spiritually both, to be safe, truly safe. If it were possible even.” In 1942, the real-life Lester shot himself on Harris Point, visible in the distance beyond the Cabrillo marker. After the only Japanese attack on California—by a sub on an oil facility near Goleta, west of Santa Barbara—in 1942, the U.S. military took over San Miguel.

Deep in the California psyche is an apparent opposition: There is a strong inclination against war prosecuted far from its shores by powers in the East (accentuated in this century by the anti-Vietnam and anti-Iraq invasion protests at the University of California–Berkeley and University of California–Santa Barbara, where, in 1970, a Bank of America branch was burned to the ground); but then there is the complicating fact that California is second only to Virginia (which houses the Pentagon) in defense dollars received, exemplified by the giant Naval port at San Diego and the testing grounds at Vandenberg and Edwards Air Force bases. The state also has the most policemen per capita of any state, outside of Washington, D.C. The tragic deaths of both Cabrillo and Herbie Lester on the Channel Islands speak loudly in their silence of the difficulty of starting anew, of the violent cost of opposing violence, even and especially in one’s past. But they also speak of a newfound pacifism not easily surrendered.

The man who named Carmel, the Carmelite chaplain of the Vizcaino expedition in 1602, Father Antonio de la Ascension, offers another example of a spiritual emphasis toward radical tolerance and military restraint. Ascension made no bones about who should be in charge of settling California: “The General, Captains, soldiers and all others who go on this expedition must be given express orders to hold themselves in strict obedience to and comply with the religious who accompany them.” Ascension insisted: “Without their orders, counsel or recommendations, no act of war or any other grievance shall be committed against the heathen Indians, even if they might provoke it.” If the military were ascendant, Ascension warned, “all effort will fail, and time and money will be wasted.”

Unlike almost everywhere else on the continent, there was no massacre of California Indians by the Spanish, at least under Junípero Serra, and, contrary to common belief, they were not enslaved or forced into the missions under Serra either (admittedly, it was hard to leave without permission). Serra chastised officials who failed to apply the phrase gente de razon (people of reason) to Indians. He went even further, insisting that, if the Indians should kill him, no retaliation by the military should be made. Could the Yokuts Indians of the San Joaquin Valley have influenced him too? They danced with their enemies.

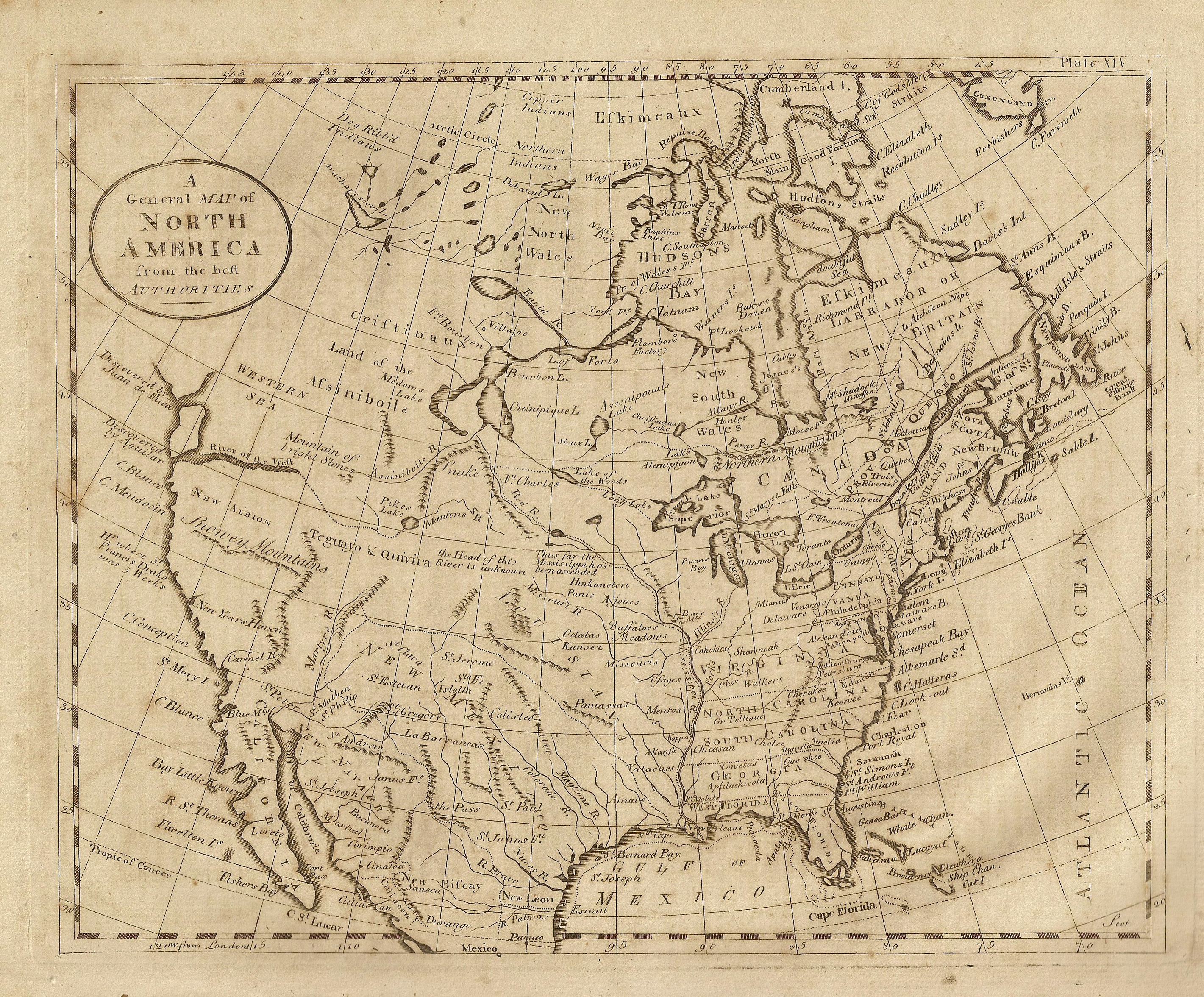

The beginning of Operation California can be traced back to a remote spot in what is now the Mexican state of Baja California Sur. In 1768, Padre Serra was clandestinely invited by Spain’s chief emissary to the New World, Jose Galvez, to plot the conquest of Nueva California (a conquest Serra called, perhaps naively, espirtual). I knew the name of the place where Galvez had planted his camp: Real de Santa Ana. Generally described as being near old, long-bust silver mining towns south of La Paz, no book or essay locates it, and, typical of Mexico for historic sites, there is no road signage. On our drive up from San Jose del Cabo, no one in the mining towns of El Triunfo or San Antonio had any idea what I was talking about. American scholars of the region could not pinpoint it either. And yet it seemed to me that the origin point of the plan to create the land that now contains 37 million people and has asserted a sort of second Declaration of Independence in the face of a runaway administration in Washington should merit at least identification or quiet ceremony.

The three men who gathered in 1768 from different corners of the globe for the historic moment in a place now lost in dust, stones, and cardon cactus could not have been more different. First, there was the man from Andalusia who owned the place where they gathered, Manuel de Ocio, the first entrepreneur in the Californias and the owner of the first rancho. Twenty years before, hearing about black pearls and black seams in grey granite, Ocio had crossed over from Sinaloa, hoping to be the first Spaniard to unlock the fabled treasures of California. Within months, however, his five-year-old son Mariano died, and, soon after, his wife Rosalia. Ocio was alone in a wasteland with his picks and shovels, a few sere cattle, and one remaining young son, Antonio. Increase and multiply, said the Bible, but for a solitudinous businessman, this meant stoke the business. Soon Ocio had the first and largest general store in Antigua California (as the Baja peninsula was called when the territory to the north was dubbed Nueva California), an early version of John Sutter, at whose general store in the Sierra Nevada a century later gold was discovered in a tailrace, launching the California Gold Rush. Ocio’s mines, however, never produced more than a thousand pounds of silver a year; he made more from beef cattle, which he free-ranged all over southern Baja, igniting disputes over land and water with the Jesuit missionaries and the indigenous people they served.

Jose Galvez, the blue-eyed, silver-wigged patrician from Madrid, had his eye on Ocio. The visitador general had been tasked by King Carlos III of Spain in a secret order to evict the Jesuits from the New World and also head off Russian and British expansion from Alaska and the Northwest into Nueva California. He later confessed that California might offer him absolution, presumably from his repressions of indigenous miner uprisings on the Mexican mainland: “I second the fervor of such holy designs, as much I desire them in the midst of the confusion my sins as a profane and wicked man have caused.” Galvez wrote Serra in Loreto that he had found a spot “with stew in abundance and plenty of accommodations.” That was Ocio’s spread.

Padre Serra hustled down on his mule the 300 miles from Loreto to Real de Santa Ana in nine days. Although Serra was already something of a legend in the New World (he had already established five beautiful missions in the Sierra Gorda mountains in central Mexico that are now a World Heritage site), some dark things weighed him down too. Three suicides appear to have been sparked by Serra’s fervor. When a woman in Oaxaca confessed her longstanding affair with a city councilman, Serra urged her to leave her lover, who then dramatically hung himself. Lashing himself during a sermon in Mexico City to imitate the sufferings of Christ, Serra caused a man to leave his pew, grab the lash out of Serra’s hand, and beat himself, saying he was the greater sinner. He died on the altar, to Serra’s shock. A woman Serra interrogated as a witch was found dead strangely just outside her cell. Long filled with the hope of meeting Indians no one from Europe had ever ministered to in Alta California, Serra was excited, perhaps even desperate, to travel north and start anew.

The three men met at the rancho out in the middle of the peninsula near a mining camp. The little man with the tonsure hugged the brocade of the patrician from Spain, but he insisted that the Indians of Alta California be given pay for their labor, as well as the friars, and later that incentives be afforded any soldier who would intermarry with an Indian. (He would also take Ascension’s rule to a new level, demanding in person to the viceroy the sacking of the military commandante of California for failure to rein in soldiers who were abusing Indian women.) Galvez revealed his four-pronged expedition—two by sea, two by land—north to San Diego. The two stirred in each other the thrill of the moment. Ocio, a man made alone by fate, stirred the stew.

(Map: Dobson’s Encyclopedia)

Of these three and the plot they hatched that changed the world, only Serra persevered. Galvez rushed back to the mainland to put down more uprisings and went insane, poisoned by his own hand or another’s back in Spain in 1787. Ocio gambled away at card games what little fortune he had and was murdered by two thieving miners Galvez had brought with him from the mainland, a “grimly ironic end,” according to Baja historian Harry Crosby. Serra went on to found the first nine of 21 Upper California missions and put his stamp on a whole new society that, though it endured its own xenophobia (against the Chinese, Mexicans, blacks) and suffered hotbeds of hatred that persist to this day, ultimately became the most welcoming to immigrants and supportive of diversity of any state in the Union.

To find Real de Santa Ana, I visited the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia offices in La Paz and sat down with Sergio Alejandro Martínez Rosas, the man in charge of education outreach for the archive. The minute I mentioned “Real de Santa Ana,” his eyes grew larger. “It is the specialty of my master at the university,” he smiled. We made a plan to meet on the steps of the Cathedral of La Paz at noon on April 30th, 2017. Soon I was shaking hands with historian Alejandro Tellechea, a humble and kind professor who got in the car with his doctoral student Sergio and led us 60 miles south, stopping only for pasteles, sugary buns they said would be critical to getting access to an old rancho from its señora. I bought two packs.

At the creaking rancho gate, a mule and pet deer came to greet us, along with a slobbering dog. Senora Manuela Rivera followed, a curly haired, slender woman with a gold-toothed smile. She accepted the pasteles graciously, declaring that her 101-year-old mother “will eat them all.” This was, indeed, the property of Manuel de Ocio’s 18th century spread. She motioned to an old warehouse where Ocio stored his corn, and a decrepit out-building with a door barely five feet high.

“But where is the old house of Real de Santa Ana?” I asked.

“That is a mile hike from here,” she pointed down yet another dusty path. “But there is little left of it.”

We set off, threading ourselves down an overgrown, narrowing path in the dust, dodging pitahaya and cardon cacti, mesquite, and here and there an untended olive tree’s branches. Our shirts caught on needles. Nothing spoke of a dwelling. Until, ducking under sticking branches, I heard Alejandro call out softly, “Aqui.”

There before us was an old half-wall of crumbled stones with a little cutout.

“That is the entry,” Alejandro pointed. “Go in.”

We stood still and looked up. The sky. And then down. A crude rectangle outlined in the dry earth of stone and brick.

“You are standing in la sala, the front room,” the good professor said. He then pointed out Manuel Ocio’s bedroom to the right, which no doubt he had given to Galvez, a smaller room adjacent for his son Antonio, which probably went to Galvez’s aides, and then—outside the perimeter line of the house—a cut-out no larger than a small cupboard.

“That is probably where Friar Serra slept on two boards,” Alejandro said. There was Serra’s signature humility, sleeping literally outside the house itself, like some broom in a closet. And then I saw it: a Corona de Cristo (or “Crown of Christ”) cactus growing in the dust right where Serra would have slept. Its round, pale red flower bloomed in the long thorns.

“It’s a holy spot,” I said to Sergio and Alejandro, and they nodded, along with another friend from San Antonio, Gerardo. We shared how this was a tense moment for our two countries, facing off over immigrants and drugs, walls and an incipient shutdown of trade. But here, a follower of St. Francis, a man with radical mercy in his heart, knitted us together long ago, Antigua and Nueva California. Pictures. Abrazos around. We would not be kept apart.

Walls crumble. The cactus erects. The spirit against tyranny blooms.

Donald Trump’s first, and heretofore only, visit to California as president was to the border south of San Diego, where he sputtered on about a wall that did not get funded. To better understand the story of that border, I spoke with Adrian Gonzalez, the great Mexican-American first baseman and perhaps the most popular player on the Los Angeles Dodgers, which has the highest attendance of any baseball team in the country, and whose fans are largely Hispanic. It was the summer of 2017, and Gonzalez was not running to cover first; he was on the disabled list for 10 days, the first time in his 14-year career. Perhaps that had put him in a philosophical mood. Though his durability is legendary, a sore elbow had not stopped hollering, and he had also re-strained a herniated disc in his back lifting up one of his two young daughters. He had celebrated, if that is the word, his 35th birthday the day before. He motioned me to a black leather couch near his locker and sat himself on its wide arm, stretching one of his legs to a low table and tucking under the other.

Born in San Diego but raised in Tijuana, Gonzalez refused to give his opinions about the wall, noting that whatever he said would cause half the people to be against you and half for you, and “social media would light up.” But he paused and looked at me carefully. “Being close to a border, tolerance is part of the culture,” Gonzalez said.

Gonzalez has relatives and friends on both sides and sees them regularly. He laughed softly telling me about his double life on two Little League teams, one in Mexico and one in the United States, playing for each, going back and forth across the border on the same day: “The hard part was—which do you play for when you get into the playoffs? A tough question.”

When I told him the story of Father Serra keeping the Spanish soldiers from drinking and washing at the “good, sweet water” of an Indian watering hole straddling the border, Gonzalez said: “That’s interesting. The rival to my high school in Chula Vista is Sweetwater High [in National City]. I’ll bet there’s a connection.” (If so, Father Serra might not approve. Sweetwater High School is home of the Red Devils.)

Gonzalez and his wife Betsy have a foundation that helps fund disadvantaged youth on both sides of the border. They paid to refurbish the Little League field in Tijuana where he played. He “goes back to his roots all the time,” and those roots naturally crisscross the border. You almost get the feeling Gonzalez’s very life has worn that border smooth. “Look,” he regarded me, rubbing a chin-strapped beard. “If you believe in Jesus, there’s no such thing as difference. We’re called to love.”

He was speaking of the wall without speaking of the wall.

“What’s it like to be part of a team?” I asked.

“It’s awesome,” he said without hesitation. “If you were to go around this clubhouse and ask every guy they will tell you and show you just who they are. You know the true person, in a sense. You can’t hide in here. Integrity comes into play. It’s a small place, a clubhouse, and a dugout smaller. It’s hard to fake it in here and easy to be fake outside.”

He was talking about fake news without talking about fake news.

“What makes California exceptional to you, Adrian?”

“You can run into anybody from any part of the world,” he said. “It’s a perfect blend of the world.” I mentioned that L.A. has some of the largest U.S. populations of people from Iran, Israel, the Arab world, Korea, and Armenia, not to mention Mexico, whose immigrants comprise L.A.’s majority. He nodded. “I love that my girls can be classmates with anyone in the world. I don’t care about your religion, skin color, race—I’m gonna love on you.”

He got a hit his first day back from the disabled list and stood on first base knocking his fists together. In catching a glimpse of his broad-faced smile, I thought of the Kumeyaay at the sight of old Junípero making sure that the jail was emptied for a greater good. And when Adrian Gonzalez, who in 2014 led all hitters in Major League Baseball in runs batted in (116), stepped to the plate for his last at bat as a Dodger in the fall of 2017, he let loose a towering home run.

Art grows on edges, and the West Coast is a literal edge, of a tectonic plate. It is also the place where the oldest adult human skeleton in North America was discovered a few decades ago, on Santa Rosa Island—the 13,000-year-old Arlington Springs Man.

In fact, the urge toward artistic expression in California is there right at the beginning of human society. The rock art and pictographs in the caves of central Baja, first discovered and mapped in detail only 40 years ago by Harry Crosby, and considered by art historians more extensive than those in Lascaux, are today a World Heritage site (and a hard one to get to). I wanted to view a cueva myself. Little did I know I would uncover an image that eluded the great Crosby and would startle anthropologists from around the world.

On April 29th, 2017, I was led by Humberto Verdugo of rural Rancho Domingo up a tortuous zig-zag trail that gave out halfway up the mountain and caused us to climb on all fours over large volcanic rocks. After a dizzying hour and a half on a near vertical hike, we caught a thin path on a ledge. I looked out on the arroyo 1,500 feet below and glimpsed fog on the Pacific Ocean; in the other direction was the Sea of Cortez. I was on the spine of the Baja peninsula. And then I saw Humberto smiling, and looked at an overhang of smooth rock, the respalda, above the dark entrance to a cave. There my breath left me.

It appeared to be a large image in cinnabar red of a blue whale. The massive, squared head narrowing to a sizable fluke, or tail, was unmistakable, and I wondered later if it might not actually be the largest toothed mammal with the largest brain, the one that riveted us as if it were a god in Moby Dick—the sperm whale. It must have been 10 feet across. Above the head what looked like a set of martini glasses, or triangles with stems, were meticulously painted. Humberto said Mexican archaeologists believe these are jellyfish. That seemed strange. Couldn’t they be an evocation of a whale’s spout?

“But look,” Humberto said in Spanish. “See the black paint at the bottom of the tail? That means the whale was dying. Probably in shallow water.”

“And the jellyfish were feeding?”

“Si. El pobre ballena.”

“How old is it?”

“Six thousand years.”

There were other images on the respalda, of an armadillo, a puffer fish, a wild turkey, a snake as curvy as any camino sinuoso on a large section of broken shelf that gave the cave its name, La Serpiente. But clearly this cave was owned by the whale. A fossil piece of whalebone stuck in the rock.

I fell going back down the mountain, bloodying my shin. The height had suddenly made me woozy. Humberto Verdugo Garcia and another guide, Cesareo “Charo” Castro, graciously helped me down. “Throw that hiking stick away and just take my hand,” Humberto ordered. His hand was weathered and strong. At the bottom, Trudi Angell, an American who runs a pack mule service in the backcountry, lived up to her name and gave me Pepto-Bismol and drops of arnica under the tongue.

But I couldn’t forget the whale. Back in Santa Barbara at breakfast with John Johnson of the city’s museum of natural history, the curator sat back in his chair at the news of my discovery and exhaled, “Wow.” He was visibly moved. It was meant to be that we were having breakfast, he said. “I’m giving a talk on whale images at an international conference on Indian pictographs in South Korea this summer and I was stumped. I have examples from Alaska and the Pacific Northwest and Mazatlan, but nothing from the place where the whales traverse freely and actually mate—the Californias. It’s a big gap.”

“Well, now it’s filled.”

“It certainly is,” he smiled.

The painter of the whale I saw would have been alive more recently than Arlington Springs Man, but his tragic story is equally timeless.

A majestic creature, larger than life, is taken down. For all his giant buoyancy, he can no longer move. What led him into the shallow water? Seduced by a starfish, a minnow that flashed red and orange? Or just old age? The jellyfish don’t care how it happened. They see a good meal and they feed. As the Fresno poet Philip Levine once wrote, “They feed they lion and he comes.”

Just who or what the whale might symbolize today, whether he could be a vain, self-obsessed politician, or our common life, even our terribly beached democracy, is up to the reader. And what if the jellyfish were not nibbling away at the whale, but paying last respects to a great dying creature—a radical mercy all their own?

All I know is the artist stood in the solitary, dry wilderness of California and something he saw cried out for expression. We shouldn’t stop that cry.

This story received support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, with additional assistance from Island Packers and the National Park Service.