The magnitude 7.8 earthquake that devastated Nepal this past weekend, leaving more than 6,000 dead and thousands of others unaccounted for, may have come as a surprise to most, but students of natural disasters and seismologists knew it was coming.

You might remember from elementary education that earthquakes are typically caused when underground rock breaks along a fault (though oil and gas industry practices are increasingly being linked to man-made quakes as well). And Nepal is situated on a site where stress continues to build, at the collision point of the Eurasian Plate and the relatively small, thin, and fast-moving Indian Plate that’s responsible for the creation of the Himalayas, described by the United States Geological Survey as “among the most dramatic and visible creations of plate-tectonic forces” we have.

The Indian Plate has seen considerable seismic activity in recent years (a 2004 earthquake in Sumatra left nearly a quarter-million dead, and another the following year in the Kashmir region of Pakistan destroyed entire villages, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information), but it’s been causing problems for much longer.

In January of 1934, a magnitude 8.1 earthquake hit eastern Nepal, causing significant damage to cities hundreds of miles away. The USGS archive of historic earthquakes describes the event in rather clinical terms:

10,700 deaths. Extreme damage (X) in the Sitamarhi-Madhubani, India area, where most buildings tilted or sank up to 1 m (3 ft) into the thick alluvium. Sand covered the sunken floors up to 1 m deep. This liquefaction damage extended eastward through Supaul to Purnia, India. In the Muzaffarpur-Darbhanga area south of the zone of liquefaction most buildings were shaken apart by “typical” severe earthquake damage. Two other areas of extreme damage (X) from shaking occurred in the Munger (Monghyr) area along the Ganges River, India and in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Large fissures occurred in the alluvial areas.

A 102-year-old man that the Times of India interviewed earlier this week, and who claims to have been living in Nepal when the 1934 earthquake hit, remembers things a bit differently.

“I was in my sugarcane field at the time of the earthquake,” Hem Prasad Timilsina told the newspaper on Wednesday. “When we heard about the destruction the calamity had wreaked in Kathmandu”—the quake is estimated to have destroyed one-fourth of the homes in Nepal’s capital city—”we walked for two days to reach here, just to marvel at what had happened. There was no system of public transport those days. You could count on your fingers the number of cars in Nepal, all owned by the rulers. … It was bad all around.”

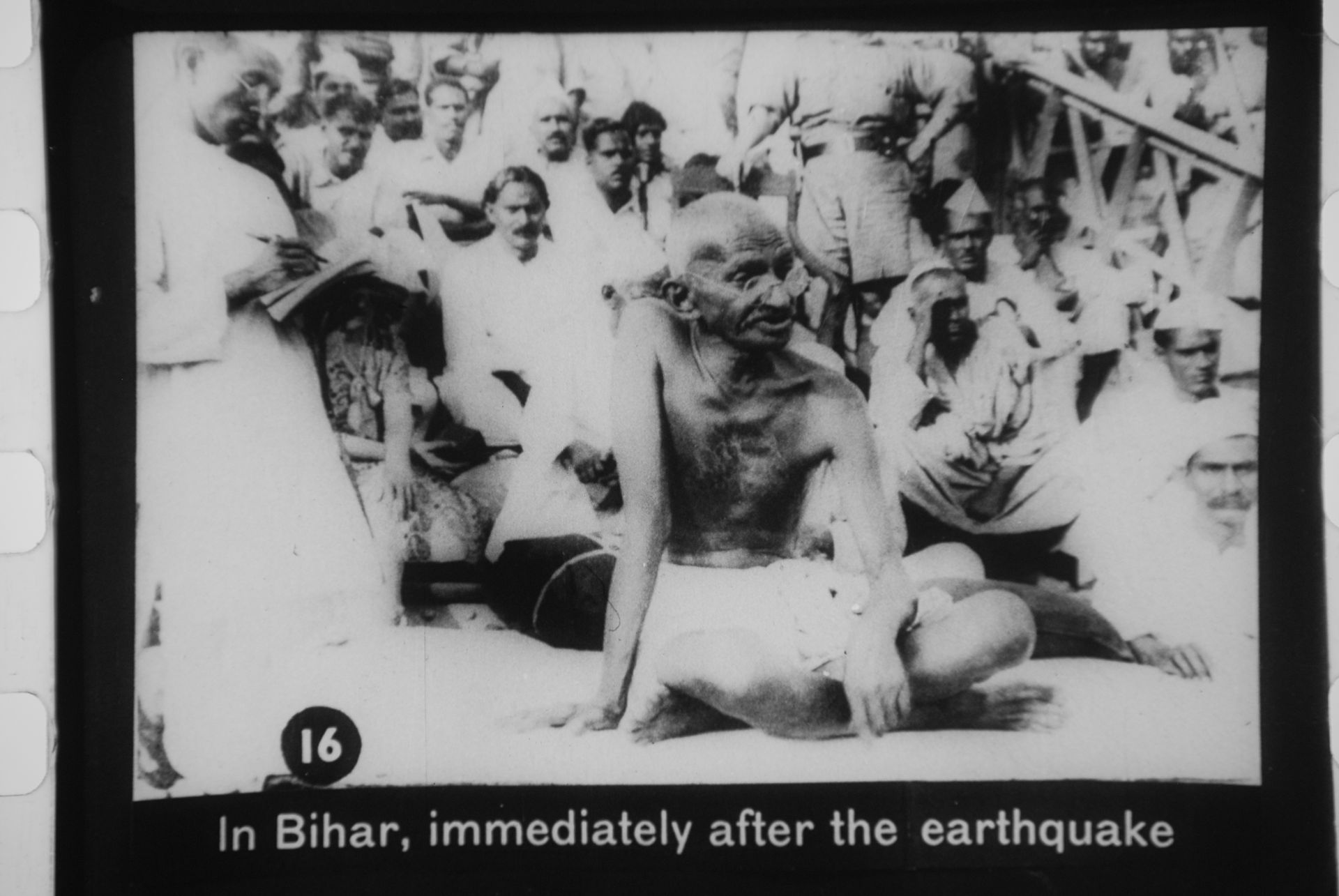

In 1934, geologists didn’t have a framework to understand earthquakes or similar processes, according to the New York Times—and they wouldn’t for another generation. At the time, Mahatma Gandhi blamed the Bihar event on divine retribution for India’s caste system, which designates a sizable percentage of the population as “untouchables,” and which Gandhi had been fighting since going on a fast against class segregation in September 1932.

What’s been described as a landmark paper was published in 1968 that dismissed Gandhi’s theory and, more significantly, convinced many of plate tectonics for the first time. Since then, we’ve made significant progress. We know now—after taking a closer look at geologic records dating back to 1255—that an earthquake of the same size hits the area around Nepal every 75 years or so, according to Nepal’s National Society for Earthquake Technology. This one was six years late.