Heat-shielding sheets of fog have been torn off the Californian orchards that produce most of the nation’s fruit and nuts. But scientists aren’t sure whether climate change, pollution, or something else bears the brunt of the blame for the withering away of nearly half the Central Valley’s wintertime Tule fog over the last three decades.

Biometeorology professor Dennis Baldocchi and graduate student Eric Waller, both of the University of California-Berkeley, recently examined 33 years of satellite data to estimate the frequency of fog days in the farm- and freeway-strewn valley. Some years were far foggier than others, but they found that the fog always arrived throughout the valley—except at the tips of the high-altitude Sutter Buttes. Their analysis unearthed a trend that could cause worries for the fruit and nut growers who produce some 95 percent of the nation’s yield.

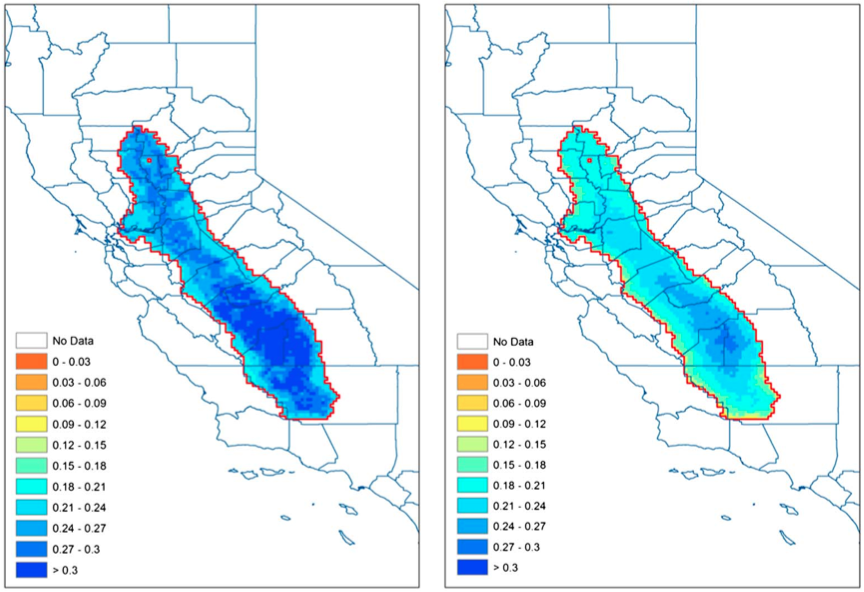

Here’s a map from their new Geophysical Research Letters paper, which shows a downward trend in the fraction of foggy days during each 125-day fog season. Average fog levels from 1981 to 1999 are on the left, with the period from 2000 to 2012 shown on the right. You can see the Sutter Buttes as a red dot in the valley’s north. The researchers found that the number of “winter fog events” decreased across the Central Valley by 46 percent during the period studied.

(Map: Geophysical Research Letters)

Growers need that fog because it keeps their farms in winter chill, a state where temperatures remain above freezing and below 45 degrees. This helps the buds stay dormant and rested. On clear days, those buds can become substantially warmer than the air around them.

The decline in fog days coincided with a decline since the 1950s of hundreds of hours spent in winter chill every year. Climate forecasts show that trend continuing. Meanwhile, droughts, such as the one ravaging California right now, reduce fogginess, because they leave less soil moisture available to be vaporized.

“I don’t want to be alarmist and say our fruits and orchards will disappear,” Baldocchi says. “Conditions that promoted a large fruit and tree industry are changing about us—and during our lifetimes. We will need to adapt, whether by new breeding programs, or changing the ranges where certain species or cultivars are grown.”

Baldocchi believes global warming, the decline in agricultural burning, and worsening air pollution may have contributed to the trend—but more research is needed to figure out what role each of those is playing. He says he is starting to gather data that could eventually help reveal whether there is a link between fog conditions and annual yields of different crops.

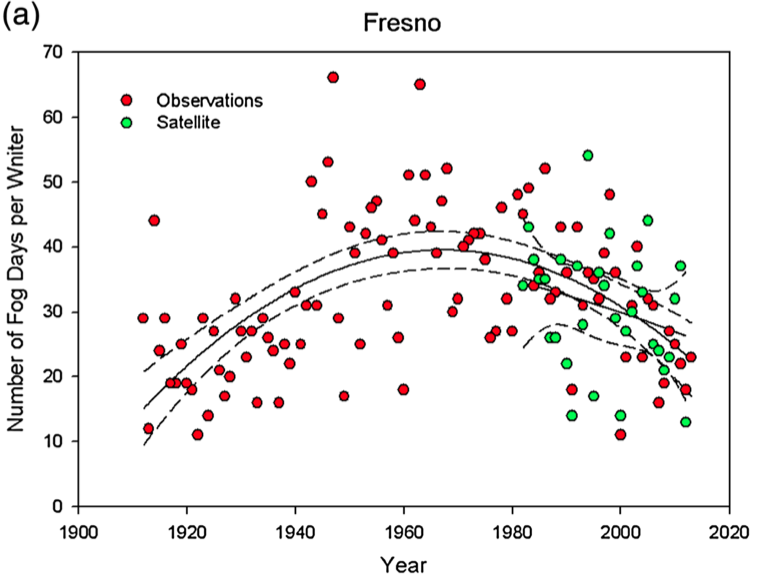

“While we observed a reduction in fog since 1980, we cannot claim this was solely due to climate warming,” the scientists write. Nor do they know whether the trend will continue—it contrasted with an earlier shift in the opposite direction. “Inspection of the ground-based fog records at Fresno and Bakersfield show that fog frequency increased between the 1940s and 1970s, then a decreasing trend in fog frequency started.”

(Graph: Geophysical Research Letters)