Forested areas in cities may seem best left untouched, but it’s a common misconception that they can take care of themselves, according to Sarah Charlop-Powers, executive director of New York City’s Natural Areas Conservancy.

“We need to undo the conception that natural areas are inherently self-sustaining,” she says. “We need to start thinking of [them] as one more type of urban parkland, and we’d never say: ‘We built that playground; we don’t need to check and make sure the equipment is in good working order.'”

That’s one conclusion to be drawn from a survey of managers of urban forests that Charlop’s group conducted with the Trust for Public Land and the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies. It’s the first national survey of people who oversee America’s “urban forested natural areas”—that is, native habitats and woods in cities, which account for 84 percent of urban parkland nationwide, according to the Trust for Public Land. (Technically, the term “urban forest” refers to all trees in a city; I use it here as shorthand for forested natural areas.)

Survey-takers represented 125 organizations in 110 cities. Most worked in municipal agencies such as parks departments, followed by non-profit organizations and state and federal government.

The upshot: Societal issues such as green-space access and the urban heat-island effect often aren’t integrated into management of urban forests. Forest managers need more data on climate change, pests, and other factors. They need more funding. And they spend much of their time dealing with invasive species and trash.

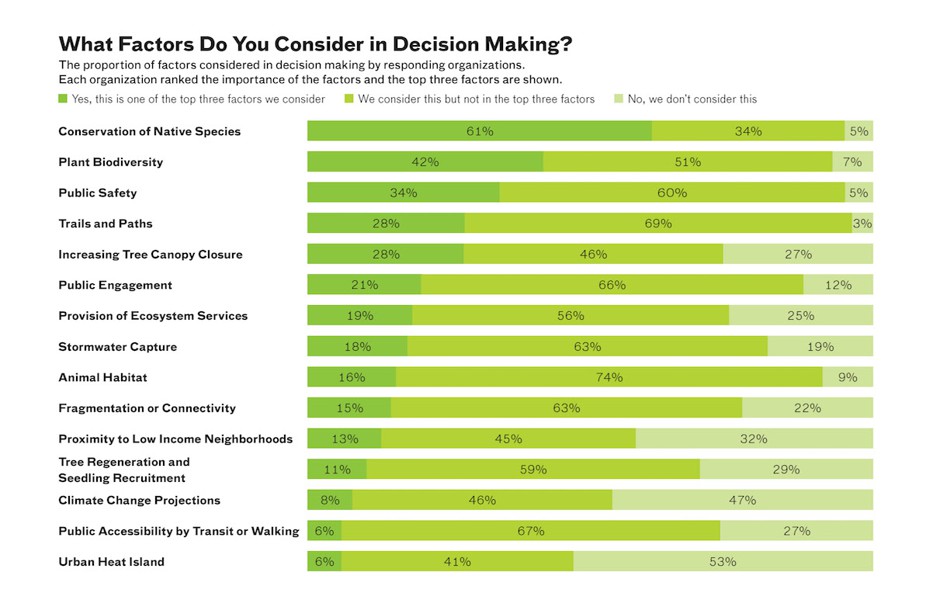

When asked about the factors that go into their decisions in forest management, only one factor was cited in the top three by a majority of respondents: native species conservation. Biodiversity and public safety were cited as main factors by a large share, but were still secondary for most.

By contrast, climate change projections and the urban heat-island effect were not considered at all by large shares of respondents (47 and 53 percent, respectively). And 32 percent did not consider proximity to low-income communities. That’s despite the fact that low-income individuals are less able to travel to experience nature away from home: A 2016 USDA Forest Service report found that 50 percent of park users in New York City said they experienced nature only in that city’s parks.

When it comes to the types of information that urban-forest managers can use to guide their work, most relied on maps of designated conservation areas and vegetation types. But 41 percent of respondents said they didn’t have data on pests and pathogens. A full 54 percent didn’t have climate change projections for the areas they managed.

As Charlop-Powers points out, the lack of data on pests is worrying at a time when the emerald ash borer is decimating forests throughout the eastern U.S. “The need to be able to rapidly respond to natural crises in the same way you’d respond to other types of infrastructure challenges feels really important and under-repesented,” she says.

Likewise, climate change projections are needed because urban forests store carbon from the Earth’s atmosphere, help control stormwater runoff, offer habitat for many species, and mitigate rising heat—yet climate change also endangers forests’ health and compromises their ability to perform those functions.

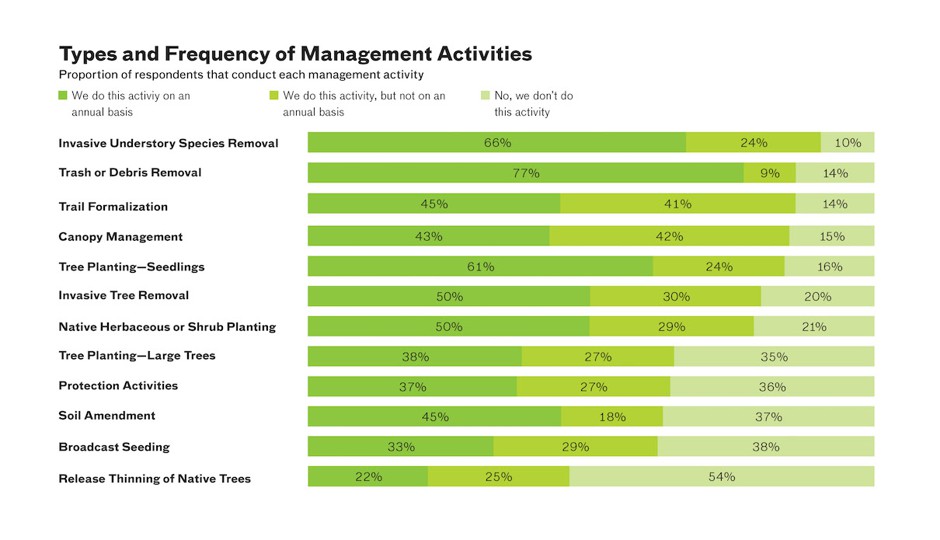

Even forest managers who have robust information may not be able to act on it as much as they’d like, because they’re so busy removing trash and fighting invasive species such as honeysuckle and kudzu. Those activities leave less time for practices like soil amendment, which improves soil and plant health.

Invasive species was identified as the biggest ecological challenge by a large majority of survey-takers (79 percent), followed by “disrupted natural processes due to the urban context” (such as runoff from roads) and “negative human use” (such as trash-dumping, vandalism, or trampling of vegetation).

Interestingly, 35 percent cited climate change stressors as “very important,” and another 33 percent called them “important”—suggesting that respondents are well aware of the threat of climate change to urban forests, but best practices and/or adequate resources to confront it are lagging. The No. 1 organizational challenge cited was limited funding or staff.

The three groups that organized the survey offer numerous recommendations in their report, including: improving access to urban forests near low-income communities; making them safer by providing maps, clearly marked trails, and easy points of entry; adding urban-forest management to city resiliency plans; creating a shared repository for case studies and data; and increasing the budget for urban and community forestry nationally.

Charlop-Powers says that she sees the results as “sobering, but also heartening in some ways.”

“It’s exciting to see that there is this unsung group of people doing this work,” she says, “and I feel hopeful as a result of what we’ve learned so far that there are real opportunities for increased impact and collaboration between cities.”

This story originally appeared on CityLab, an editorial partner site. Subscribe to CityLab’s newsletters and follow CityLab on Facebook and Twitter.