As the last ancient Egyptian civilization teetered toward chaos, its people faced famine and disease, abandoned their land, and rioted against elites. But behind this political unrest, new evidence suggests, there may have been a more explosive force.

In a new study published Tuesday, a team of climate history researchers say a series of explosive volcanic eruptions stymied annual floods of the Nile River, triggering socioeconomic unrest—and, eventually, the downfall of the Ptolemaic Kingdom, which ruled much of Northeast Africa and the Middle East.

During the Ptolemaic period, from 305-30 B.C.E., volcanoes in Alaska, Russia, and Greenland injected sulfurous gases into the stratosphere, cooling the surface of the hemisphere and weakening the atmospheric forces that drive monsoon winds. The resulting decrease in rainfall curtailed the Nile’s floodwaters.

Ancient Egyptians relied on these floods to sustain their agriculture. “It’s the basis of civilization, it’s the basis of life,” says the study’s co-author, Joseph Manning, a historian at Yale University. Without this water source, crops withered, the people starved, and revolts broke out across the kingdom.

“From what we can see there is a connection between Nile flood suppressions—that means less water, fewer crops, sometimes crop failures—and periods of social unrest,” Manning says. “We think the connection is that these flood failures reflect underlying social problems.”

Manning and co-author Francis Ludlow used ice-core records from volcanic ash to compare eruptions with historical records, written in Greek and Egyptian on papyrus, which told a revealing story: As the floods waned, food become scarce, people hurriedly sold off land, and the government failed to collect taxes. These patterns of unrest coincided almost exactly with the eruptions—evidence of what Manning calls “climate shock.”

Manning is clear that volcanoes do not cause social unrest directly, but he does say these climate shocks are “revealing and even pushing along these social problems.”

“There’s a lot of underlying social issues, and along comes a Nile flood failure,” he says. “In the cases of severe social unrest and multiple years of Nile flood failure, we’re talking about food scarcity, in some cases famine.”

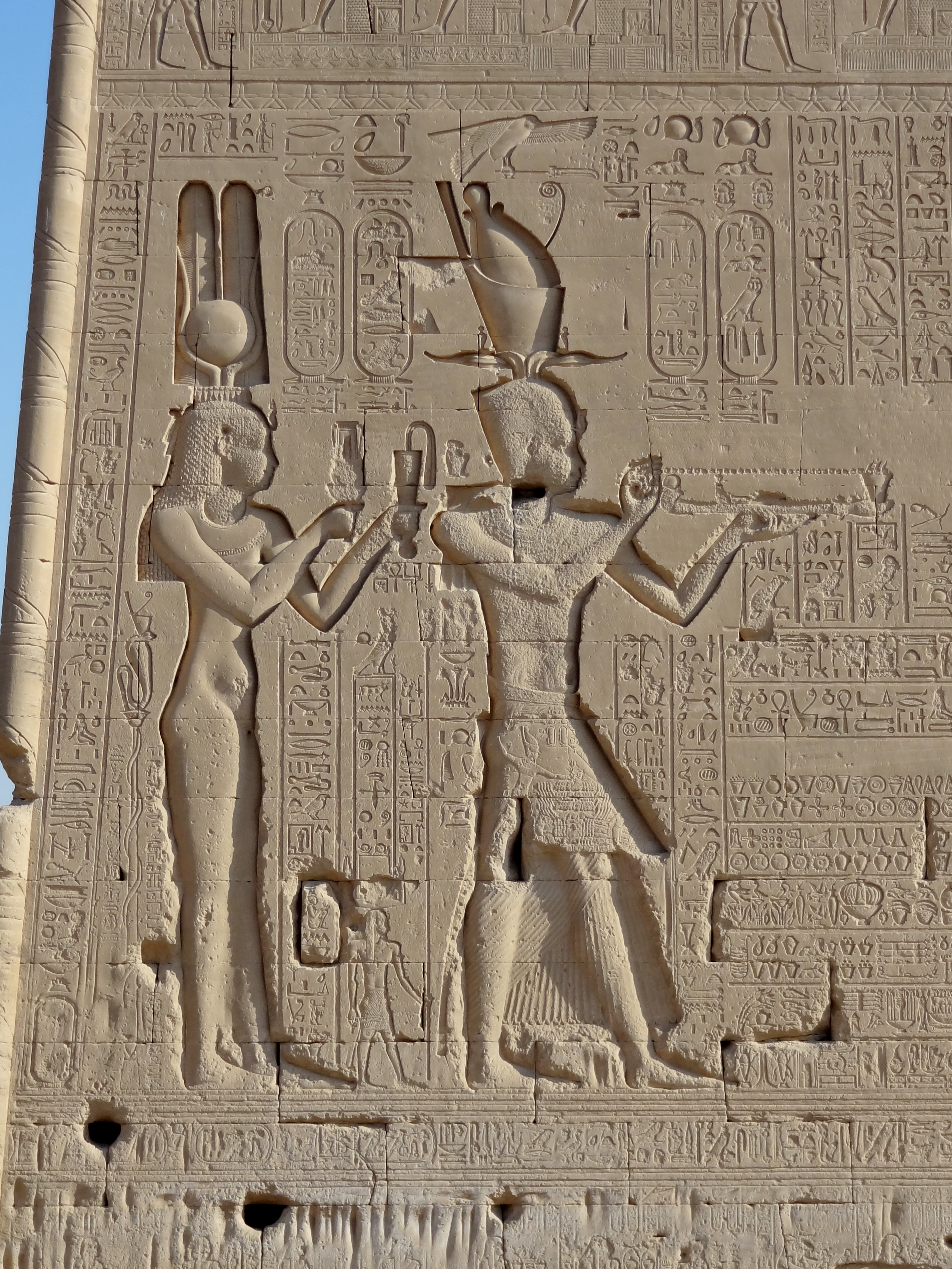

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The Ptolemaic Kingdom ended with Cleopatra’s death, but its lesson remains ingrained in ash, preserved in ice to be analyzed centuries later.

“We showed that society can be vulnerable to shocks without them knowing about it,” Manning says. “With these kinds of climate shocks, we sometimes don’t know when they’re coming…. That has to be built into the political system.”

Another climate shock might not be too far off. The Earth’s volcanoes have been quiet for the 20th and 21st centuries, but that could “change at any moment,” Ludlow writes in an email exchange.

“Add to that the fact that the Nile is predicted to become even more variable as human-driven climatic change proceeds, and you certainly have a recipe for severe flood failures with future big eruptions,” Ludlow writes.

With tensions rising between Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt amid the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, Ludlow adds that another period of drought could have dire social and political consequences.

The Ptolemaic state failed to quell unrest when its rulers neglected to store grain for the long term, but Manning says they can’t be blamed—after all, they didn’t have the foresight or technologies we do.

When the next explosions rock the stratosphere, we’ll have no excuse.