Documentary filmmaker Ken Burns says the National Park program is America’s best idea. A new study, however, says it could be better. Our land protection strategy is exactly the opposite of what we should be doing to protect endangered species. The country’s most vulnerable creatures—those with small ranges or those found only in the continental United States—live mostly in the Southeast. Our protected lands, especially the jewels of the National Park System, are concentrated in the West. Doh!

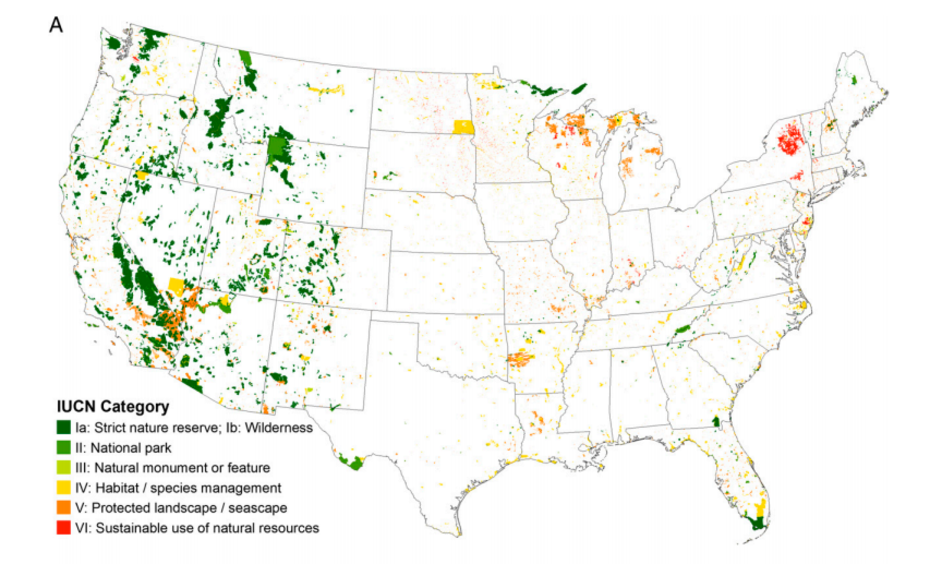

The map below, generated by study author Clinton Jenkins of the Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas in Brazil, shows which U.S. lands have some form of legal conservation status. The different colors represent the degree of protection, as defined by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Dark-green areas have the strictest limits on development, where the land is managed for the exclusive benefit of wildlife. At the other end of the spectrum are the red areas, like the Adirondacks, where conservation is just one goal in a more flexible system of land management. The white parts—the overwhelming majority—have no legal protections. That’s where you and I live, work, and drive our noisy, polluting cars. The takeaway here is that our conservation plan is very West-centric.

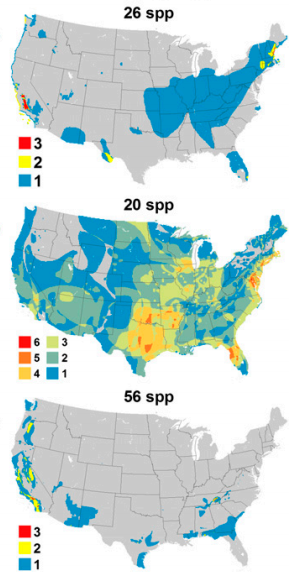

Now look at these maps, which depict the geographic distribution of animals designated as vulnerable by IUCN, with red representing areas with the most species in some danger of extinction. (By the way, browsing the IUCN Red List database of threatened and endangered species is an edifying way to waste a few hours.) The first map is dedicated to mammals, the second to birds, and the third to amphibians.

The mismatch should be obvious—our most vulnerable species are not living in protected areas.

If you’re a skeptic, you’re probably wondering if we’re confusing cause and effect: Perhaps the vast open spaces of the West have so few threatened species because of the protections. Good thought! Unfortunately, it’s wrong, and I have more maps below to prove it.

The focus of much conservation activity is on protecting endemic species, which live only in one area. If those species lose their habitat, they have nowhere else to go. These maps show the concentration of endemic species in the United States. The left column represents mammals, birds, and amphibians, in descending order. The right column depicts reptiles, freshwater fish, and trees.

There are some endemic species in and around our western protected areas, but the real hot spots are clearly in northern Florida, Georgia, and the Appalachians. If the West were a paradise for animal and plant life, and the unprotected East a barren wasteland, these maps would look very different.

The mismatch between our conservation strategy and the needs of threatened species is a combination of historical quirks and economic priorities. John Muir, arguably our most famous naturalist and one of the driving forces behind U.S. land conservation strategy, was more interested in saving landscapes than species. Reflecting on his time in Yosemite with Muir, Theodore Roosevelt wrote in 1913, “John Muir cared little for birds or bird songs, and knew little about them. The hermit-thrushes meant nothing to him, the trees and the flowers and the cliffs everything.”

Don’t judge Muir too harshly. Extinction wasn’t a concept that humans fully understood until the late 18th century, so species protection wasn’t a top priority in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Once we finally started worrying about extinction, the focus was on a small number of prominent creatures.

“Early wildlife conservationists—men like Theodore Roosevelt and George Bird Grinnell—were primarily hunters and anglers,” says Matt Skoglund, director of the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Northern Rockies office as well as a passionate hunter and angler himself. “They were worried about species like bison, elk, moose, salmon, and ducks. Salamanders and butterflies weren’t getting their attention.”

Tiny, economically insignificant species are precisely the ones we need to worry about now in the Southeast. The bluemask darter, for example, is an endangered fish living in the Caney Fork River system in Tennessee. The Weller’s salamander is another endangered species, living in the high southern Appalachian Mountains.

Economics and simple timing has also dictated much of the U.S. land-protection strategy. By the time government officials began to think about setting aside wilderness, much of the Eastern United States had already been converted into farmland and cities. The federal government owned huge, agriculturally unproductive tracts in the West, which made it a convenient starting place for conservation.

There’s still plenty we can do to save the country’s creatures, though, without declaring the entire southeastern United States a national park. For instance, we can protect areas from development and sensitive waterways from overuse and pollution. Jenkins and his co-authors suggest a few good places to start: the Blue Ridge Mountains; the Sierra Nevada; the California coast; the watersheds of Tennessee, Alabama, and northern Georgia; the Florida Panhandle; and a few others. None of this is to say, of course, that we should abandon our great western parks, which host diverse ecosystems also worthy of our concern.

“Species like grizzly bears and wolverines need a big, connected landscape, which is why it’s important to protect open spaces in the West,” Skoglund says. “It shouldn’t be an either-or. We should protect both.” (And all that lies in between, too.)

This post originally appeared on Earthwire as “America’s Best Idea, Executed Poorly” and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.