Since April 15, an unusually high number of wildfires—122—have sparked in Washington State.

The Evergreen State is probably not the first place that comes to mind when you think of wildfire. But across much of the West, extended drought, dismally low snowpack, and predictions for a warm, dry summer have sparked concerns that this fire season could be among the most destructive and costliest ever.

And that’s coming on the heels of recent seasons when the federal government blew its roughly $1 billion wildfire budget again and again. (The United States Forest Service estimates that one percent of fires—the megafires—consume 30 percent of the funds.) In all, federal, state, and local governments spend an estimated $4.7 billion a year on wildfire suppression, according to the International Association of Wildland Fire. Forest managers aren’t only concerned about the usual suspects, like California; they’re worried that conflagrations might consume areas that don’t usually burn, including the usually wet, lush Pacific Northwest.

“Things are not looking good,” says Sandra Kaiser, communications director for the Washington State Department of Natural Resources. The governor declared a statewide drought emergency on May 15, and the wildfire season, which runs through September, is just getting started. “There is concern that years of drought have really weakened the forest and created a much more explosive situation.”

While there’s no crystal ball for forecasting wildfire, experts have come to expect fiercer and more frequent blazes. “It’s almost a forgone conclusion that there’s going to be a very, very bad fire every year,” says Jerry Williams, who retired as the U.S. Forest Service’s top fire manager in 2005 and is now a fire adviser. Increasing temperatures and parched conditions are priming wild lands to burn, fire seasons are lasting longer, and decades of poor management have allowed fuel, such as dead trees and brush, to build up. It wouldn’t take much.

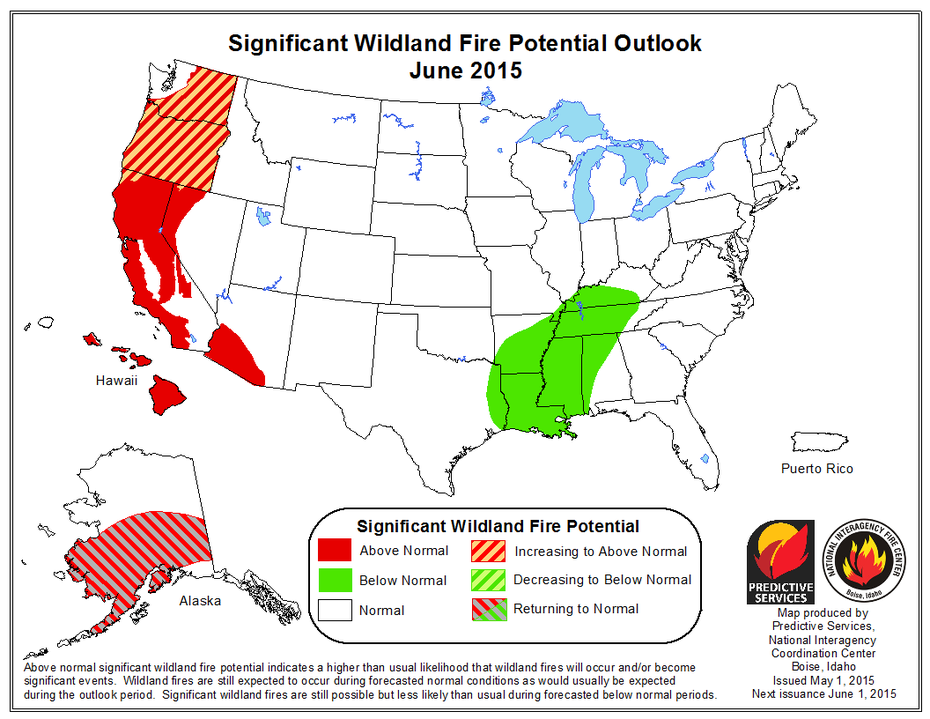

HOT SPOTS

California is in the spotlight. As of May 18, the state has battled 1,406 wildfires that collectively torched 6,009 acres, well above the five-year average of 845 fires and 5,475 acres burned. “California is always a concern,” Williams says. “But the drought looks so pervasive and deep that this year it is very bright on most radar screens.”

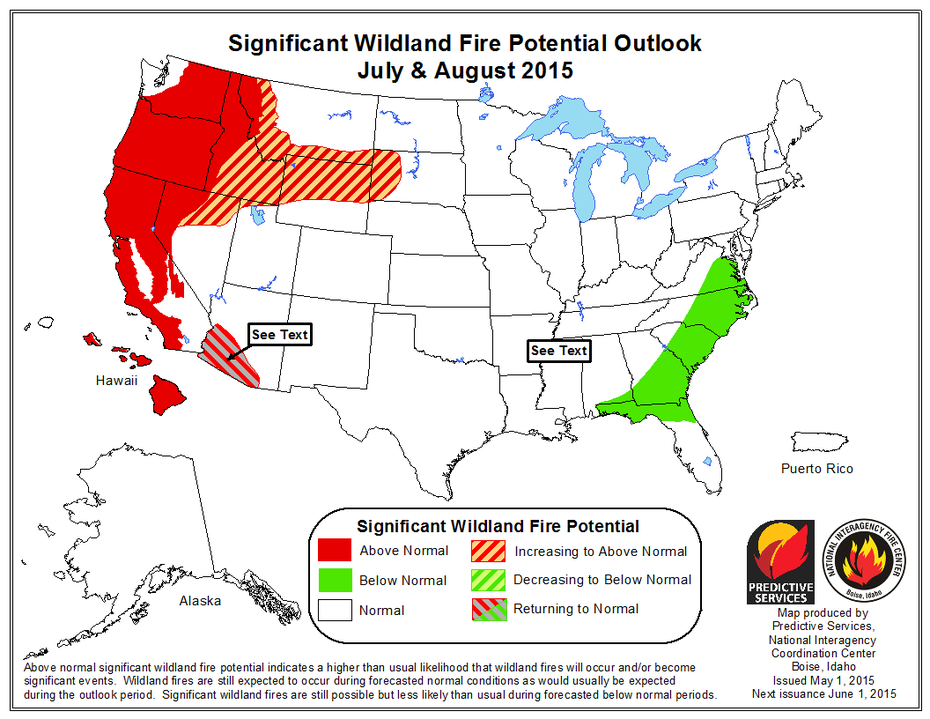

Once summer hits, more of the West will be at risk, too, says the National Interagency Fire Center. Greater than usual potential for wildfires will extend across the Pacific Coast states, expanding into the northern Great Basin and northern Rocky Mountains.

Along with drought and abundant tinder, weather will play a role, too. If El Niño conditions continue as predicted, areas south of central Colorado are expected to receive more moisture, resulting in a normal fire season in the southwest, says Wally Covington, director of the Ecological Restoration Institute at North Arizona University. Areas to the north, however, might not be so lucky. They are expected to receive less precipitation than normal. “We’d expect to see more dynamic fires in that area,” Covington says.

Washington experienced its worst fire season ever last year, with more than 400,000 acres burned, Kaiser says. Typically, fires burn on the eastern side of the Cascade Mountains. This year could be even worse than 2014 due in part to abnormally dry conditions on the western side of the mountains. “The forests are so much denser there, so once a fire gets started it moves quickly and it’s much, much more difficult to put out,” she says, adding that the DNC has requested $4.5 million from the state legislature for more trucks and crews.

HOME PROTECTION

Wildfire threatens 1.2 million homes in 12 western states, and experts are encouraging homeowners to take steps to prevent their houses from going up in flames. The idea is to create a buffer between abodes and forests or grasslands by trimming trees and removing dead vegetation wherever you find it. California has led the way, and state law requires 100 feet of defensible space around homes. But other states, including Washington, are also ramping up efforts to spread the word to communities about what they can do to prepare for firestorms.

FIRE PREVENTION

Clearing brush away from homes is unquestionably important, but to really beat back catastrophic wildfires will require a landscape-scale approach. “We’re putting a lot of effort into better firefighting, bigger air tankers, more people, bigger budgets,” Williams says. “But that’s not translating into prevention and mitigation.”

The key, experts say, is returning forests to more natural, less dense stands, whether by thinning, prescribed burning, or logging (while preserving old growth). Covington points to the 4FRI project in Arizona, where some of that work is being done. The project aims to thin 2.4 million acres of overgrown ponderosa forests over a couple of decades. It’s a start, he says. “The challenge is doing it on a scale that’s actually going to be helpful.”

So far, preventative methods are only being carried out on a very small percentage of lands at fire risk. A single wildfire can burn hundreds of thousands of acres, but according to Williams, thinning crews are treating less than 300,000 acres.

“We’re in a race to the rail crossing,” Williams says. “Whether we come to that realization in time or not is the real question.”

This post originally appeared on Earthwire as “Fearing the Burn” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.