Knowing where deforestation is happening is critical for efforts aimed at stopping or slowing it. Major breakthroughs toward this goal have been made over the previous few years, with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) harnessing the power of satellites to monitor and identify canopy loss in forests around the world. Now, a new study sheds more light on forest loss, determining the primary causes of deforestation around the world.

In 2014, World Resources Institute and partners launched an online platform to help governments, companies, and NGOs fight deforestation on a global scale. By taking advantage of the latest satellite and cloud computing technologies, the platform, called Global Forest Watch, monitors the world’s forests in near-real time, providing tools, data sets, and maps to track forest loss.

But not all causes—or “drivers”—of forest loss are equal in terms of impact, with some much more destructive, permanent, or preventable than others. Large-scale conversion of forest for agricultural land to grow commodity crops like oil palm and rubber tends to be more ecologically damaging than, say, occasional logging or wildfire.

“Knowing whether or not a forest is lost permanently to a new land use like agriculture or is expected to regrow over time has major implications for improving our understanding about the role forests around the world play in influencing the global carbon budget,” said Nancy Harris, research manager at Global Forest Watch. “Forests can be either net sources or net sinks for atmospheric carbon depending on how we manage them.”

However, the satellite tech behind forest monitoring platforms is unable to discern the underlying drivers of tree cover loss. Global Forest Watch, for instance, visualizes this as a rash of pink splashed across the world’s continents, growing especially dense in places like Brazil, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

But a new study attempts to upgrade this essentially monochromatic view of tree cover loss by identifying the main drivers of deforestation on a regional level. Its results were published this week in Science, and are visualized on Global Forest Watch.

A team of researchers from WRI, the Sustainability Consortium, and the University of Maryland developed this new map by looking at thousands of satellite images in Google Earth to create a predictive model. They then used this model to determine the most dominant driver of forest loss in a given 10-kilometer-square area between 2001 and 2015.

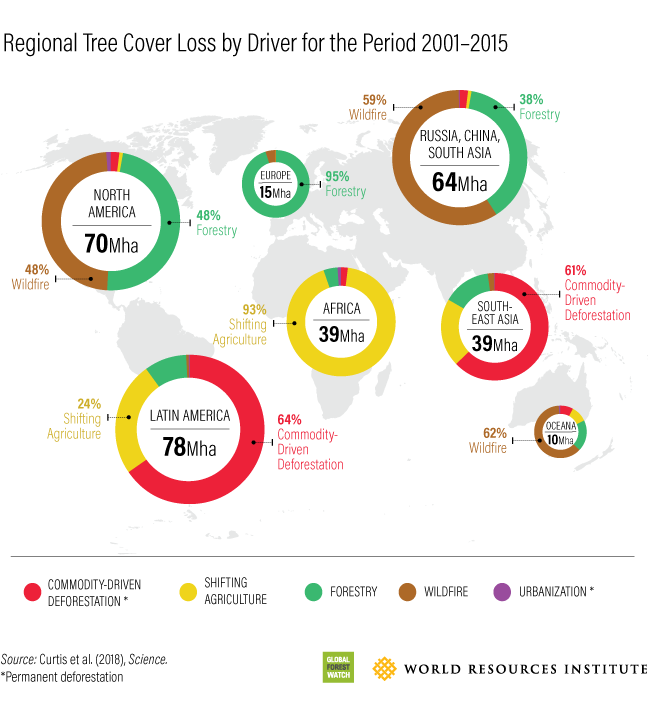

Overall, they found that 27 percent of all forest loss—50,000 square kilometers per year—is caused by permanent commodity-driven deforestation. In other words, an area of forest a quarter of the size of India was felled to grow commodity crops over 15 years.

“Hundreds of companies have publicly committed to the sustainable production and sourcing of global commodities like palm oil, soy, beef, and gold,” said Harris, who was co-author of the study. “For the first time, we can now quantify how much tree cover loss is due to commodity production and evaluate the collective progress of companies toward meeting their commitments. Our results show that much work is left to be done.”

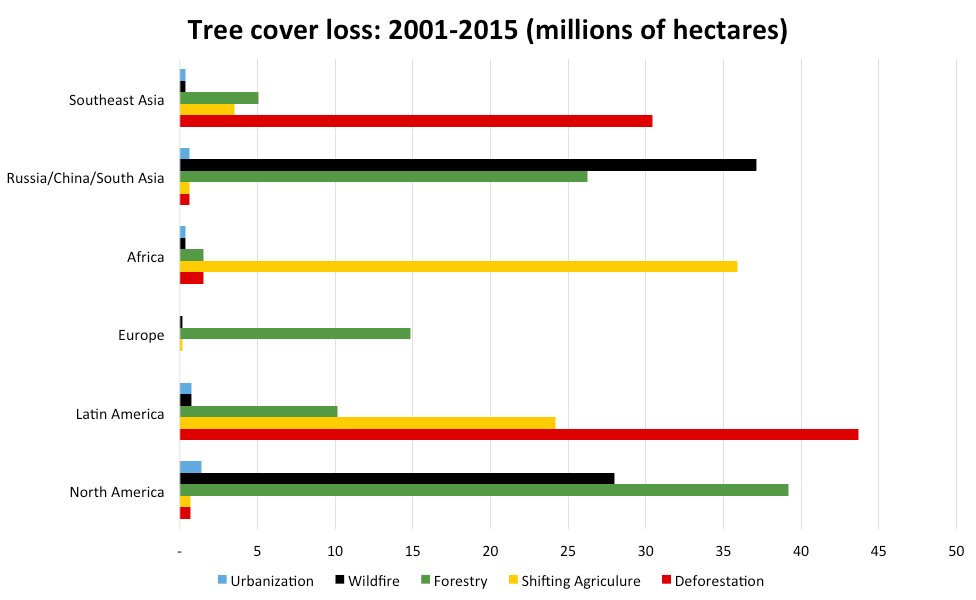

The next-biggest driver of forest loss worldwide is forestry at 26 percent; wildfire and shifting agriculture amounting to 23 percent and 24 percent, respectively. The study finds less than 1 percent of global forest loss was attributable to urbanization, with around 1 percent caused by something other than these four main drivers.

“There are public misconceptions that urbanization is a significant direct driver of overall deforestation rates because it is a change in the landscape that populations are, by definition, highly exposed to. Our results demonstrate that urbanization is a very minor driver of tree cover loss globally, which may be surprising to some people,” Harris said.

The study indicates commodity-driven deforestation is concentrated primarily in Latin America and Southeast Asia. In Latin America, row cropping and cattle grazing were found to be the primary drivers of forest loss, while oil palm cultivation is the main cause in Malaysia and Indonesia. The study’s authors write that their results indicate these places should be targeted as key locations for eliminating deforestation from supply chains and developing policies designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation.

Forests aren’t just important for wildlife; they are also critical storehouses of carbon and feature prominently in major multinational efforts to combat global warming.

“The conservation, restoration, and improved management of tropical forests, mangroves, and peatlands could provide a quarter of the cost-effective mitigation action needed by 2030 to meet the Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to two degrees,” Harris said.

The study found commodity-driven deforestation remained constant throughout their 15-year study period, which the authors say indicates corporate zero-deforestation agreements may not be working in many places.

“Despite corporate commitments, the rate of commodity-driven deforestation has not declined,” the researchers write in their study. “To end deforestation, companies must eliminate five million hectares of conversion from supply chains each year.”

The study’s authors write that, while wildfires, shifting agriculture, and forestry technically allow for regrowth, further study could provide a more nuanced understanding of the effects of these drivers. For instance, they say that shifting agriculture in Peru is typically well managed, while this type of forest loss in Sub-Saharan Africa might lead to more long-term damage. Understanding where shifting agriculture plays more of a role in forest degradation could be important for companies that source from smallholder farmers, they write.

The researchers hope their findings will help increase accountability and transparency in global supply chains. Now, they say, the nearly 450 companies that have set goals to eliminate deforestation in their supply chains have a clear map of priority areas to target for certification and traceability.

“The analysis makes visual what we already knew—that the causes of tree cover loss vary significantly around the world,” said the authors in a statement. “This new information will enable companies, governments, and concerned citizens to recognize where efforts should be focused to achieve deforestation-free supply chains and to identify and act where other drivers are causing an unwanted increase in tree cover loss.”

This story originally appeared at the website of global conservation news service Mongabay.com. Get updates on their stories delivered to your inbox, or follow @Mongabay on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.