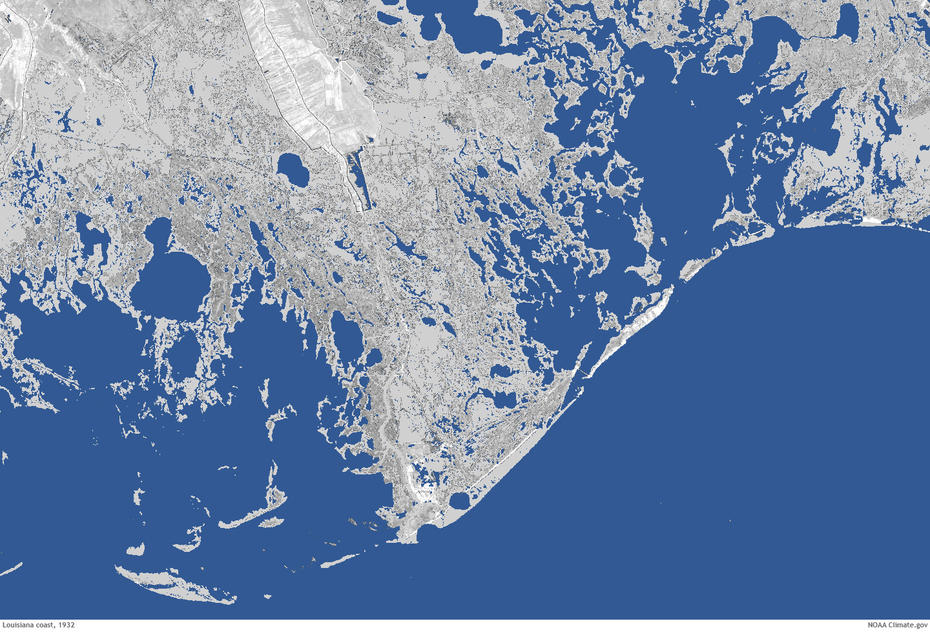

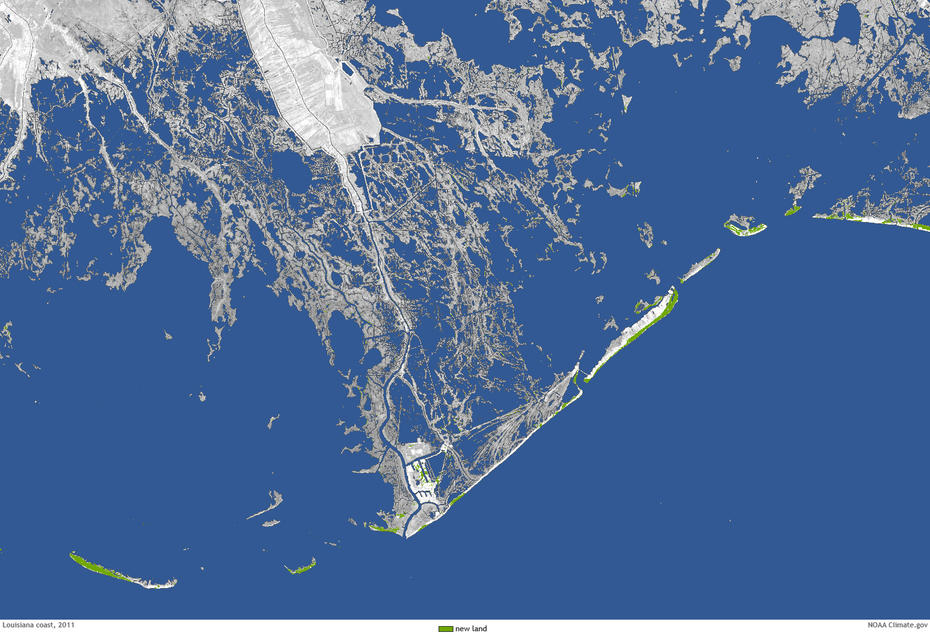

Hurricane Katrina was a terrible storm, but its effects needn’t have been so catastrophic. Wetlands along Louisiana’s Gulf Coast should have buffered the state and its residents. They could have supported the levees designed to hold back the water. They would have reduced the flooding of Louisiana’s cities—but the wetlands aren’t there anymore. The state, which loses about a football field’s worth of land per hour to the sea, is approximately 2,000 square miles smaller today than at its modern maximum of less than a century ago.

No one disputes that Louisiana is shrinking, and no one disputes that oil and gas exploration has contributed to the problem—canal-building and well-drilling expose the marshland to seawater, accelerating its subsidence. The state even has a blueprint to fix the problem, known as the Coastal Master Plan. Remarkably, almost everyone supports it.

There’s just one little disagreement: How much of the bill should be sent to the oil and gas industry?

Actually, the disagreement isn’t that little. We’re talking about a lot of money. Halting the disappearance of Louisiana’s coastal lands will cost a minimum of $50 billion, possibly closer to $100 billion. For perspective, the California high-speed rail project, now projected to cost $68 billion, is widely described as “the most expensive public-works project in United States history.” Protecting the Louisiana coast could dwarf that.

The state’s oil and gas industry, easily worth tens of billions of dollars itself, isn’t solely responsible for the damage. The insults to Louisiana’s marshes are manifold and have been taking their toll for decades. The building of upriver dams has starved the Mississippi of the sediment that would naturally settle at the mouth of the river, where freshwater meets the ocean. That sediment built and sustained the marshlands over seven millennia. Levees constructed closer to New Orleans locked the Mississippi into a single (not entirely natural) course, which further halted the dispersal of mud. The Gulf Intracoastal Waterway—built in the 1930s and ’40s to protect U.S. shipping from German U-boats—allowed salty ocean water to eat away at the marshes.

The contribution of oil and gas interests, however, is substantial. Starting in the early 1900s, the industry began drilling wells deep into coastal lands, installing thousands of miles of pipeline and digging its own canals to bring machines in and oil out. These scars on the marshlands bring more land into contact with both salt and freshwater, hastening the land’s collapse.

John M. Barry, a best-selling historian and a recognized authority on flood control, offers a useful analogy: A block of ice, once taken out of the freezer, will begin to melt, but slowly. Pockmark the block with an ice pick, and it will melt much faster. Along the melting Louisiana coast, the oil and gas industry has wielded the ice pick for more than a century.

Putting a precise figure on the industry’s contribution to the problem, however, is a challenge. Scientists working for oil and gas interests concede that 36 percent of the marshland subsidence is due to their employers’ activities. The U.S. Department of the Interior says the industry’s responsibility lies somewhere between 15 percent and 59 percent. Louisiana State University wetlands expert R. Eugene Turner has suggested that the figure is closer to 90 percent.

Who’s right? It doesn’t really matter at this point, because fossil-fuel interests aren’t willing to pay restoration damages that approach even the lowest estimates of their proportional responsibility. Barry estimates that their contributions to wetland restoration are in the tens of millions, at best.

“It’s as if your $25,000 car were hit by a truck, and the driver offered you $10 to call it even,” he explains. “As ridiculous as it sounds, that’s the approximate ratio of what they’ve paid to their actual liability.”

In his time on the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-East, a board formed by the state legislature, Barry helped launch a lawsuit against a host of oil and gas companies. The move caused a firestorm of opposition in the government, where many officeholders have received substantial donations from the corporate defendants. As of this writing, the case has seen a setback in the federal courts and a win in the state courts. (It’s alive, but I wouldn’t necessarily say it’s well,” says Barry, who has since been relieved of his place on the flood-control board.)

Author Nathaniel Rich’s account of how powerful interests in the state capital of Baton Rouge tried to kill the lawsuit, published last year in the New York Times, is eye-opening. It’s the story of an industry so powerful that it can shift its financial responsibilities to the state and federal governments, with the willing support of the taxpayers. This isn’t a question of too big to fail, since the lawsuits would not bankrupt the fossil-fuel industry. Rather, these companies have become so important to the Louisiana economy that they’re too big to be held accountable.

It’s still too early to say who will pay to save Louisiana’s coastline, but there’s no doubt that taxpayers around the country will shoulder a disproportionate share of the burden. We might not like it, but we all have something at stake. Coastal wetlands along the Eastern seaboard, for example, are being lost twice as fast as nature can build them. When the marshes are gone, we’ll all be Louisianans, more or less.

“We need a shoreline solution for the entire country, not just Louisiana, or we’re going to face a disaster,” says Val Marmillion, managing director of America’s Wetland Foundation. “The sooner everybody gets on board, the better the solution will be.”

So get on board. The door is open, but the ride ain’t free.

This post originally appeared on Earthwire as “Who Should Pay to Restore the Louisiana Coastline?” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.