The following is an excerpt from “The Human Mind,” an essay by Steven Pinker that appears in The Harvard Sampler: Liberal Education for the Twenty-First Century.

People often think of psychology as the study of the weird, the abnormal, the striking — of prodigies and psychotics, saints and serial killers. But the heart of psychology is the study of pedestrian processes like vision, motor control, memory, language, emotions, concepts, and knowledge of the social world. And the starting point I recommend for appreciating these processes is not the study of extraordinary people; it is not the study of people at all. It is robots. If you had to build a robot that does the kinds of things we do as we make it through the day, what would have to go into it? How would you get it to see, move, remember, reason, deal with other people, deal with its own needs? Here is just a sample of the feats a human accomplishes without reflection but which represent formidable engineering challenges in the design of a humanlike robot: …

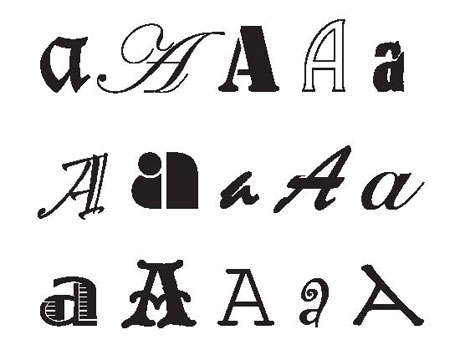

To negotiate your world, not only do you have to perceive the shapes in it, but you have to assign each one to a category, like a particular tool or a face or an animal. One only has to look at the different shapes that we categorize as an example of the letter A or imagine different chairs (dining room, office, wheelchair, recliner, director’s, beanbag) to appreciate the feats of abstraction that go into shape recognition.

Once again, you have to think like an engineer to appreciate the complexity in the natural. The oddly shaped numbers at the bottom of your checks were designed many decades ago so that their contours would overlap as little as possible and they would be readable by electronic circuitry, because even the best computers would have been flummoxed by the ordinary printed numbers that any child can read.

The Jan-Feb 2012

Miller-McCune

This article appears in our Jan-Feb 2012 issue under the title “The Feeble Robot Mind.” To see a schedule of when more articles from this issue will appear on Miller-McCune.com, please visit the

Jan-Feb 2012 magazine page.

Of course today, shape recognition by computer is far more sophisticated, but it is still no match for a human. That is why, when you open a Yahoo! account (or visit other protected websites), you have to read and type in the letters in a distorted “captcha” display to prove you are not a spambot. A human can read the distorted text; at least for the time being, no computer algorithm can. …

Today, you cannot buy a household robot that will put away the dishes or run simple errands. That is because the feats that go into understanding a sentence or grasping a glass, though they are literally child’s play, are beyond the limits of current technology. The challenge of designing a robot with simple human skills is one way to emerge from the “anesthetic of familiarity,” as the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins has called it, and to become sensitive to the complexity of the human mind.

Sign up for the free Miller-McCune.com e-newsletter.

“Like” Miller-McCune on Facebook.

Follow Miller-McCune on Twitter.

Add Miller-McCune.com news to your site.