Smokey Bear’s well-worn catchphrase—that “only you can prevent” forest fires—is sounding all the more naive as a new reality settles into the oft-tinder dry American West.

The numbers of big fires that strike annually are on the rise throughout most of the region, from the Rocky Mountains’ pine forests to the wind-whipped deserts that border Mexico. Worsening droughts are taking searing tolls, helping to nudge vast biomes into combustion. The only region spared seems to be coastal California—and, even there, in the relative respite of a Mediterranean climate, the amount of land affected by large fires continues to grow.

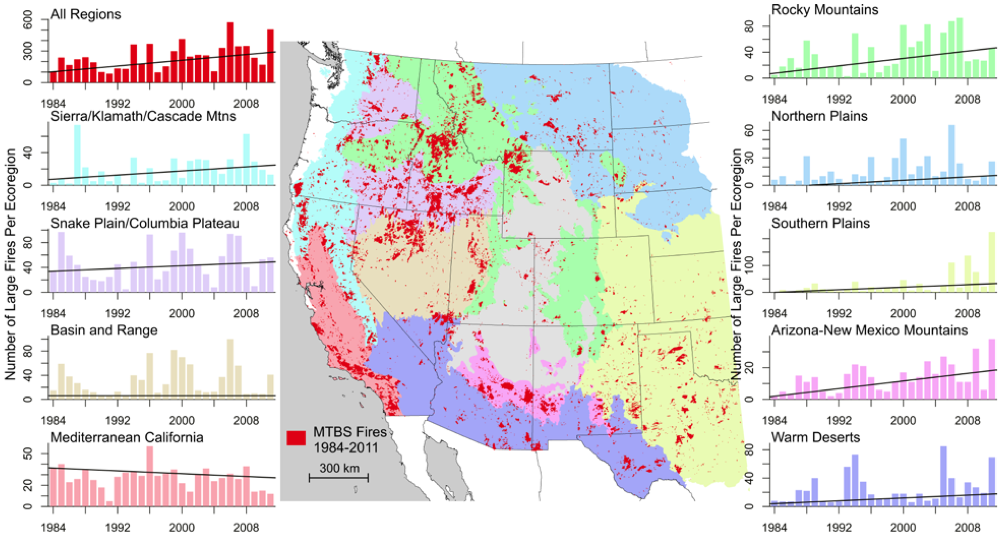

Researchers recently pored over satellite fire data and climate data before concluding that monster wildfires—the types of uncontrolled blazes that tear through at least 1,000 acres of forests, parched grasslands, and neighborhoods—increased at a rate of seven every year throughout the region from 1984 to 2011. That helped push the amount of area that burned in such blazes up by an average of nearly 90,000 acres every year.

Check out this chart from the new paper, published in Geophysical Research Letters:

(Map: Geophysical Research Letters)

We asked Philip Dennison, who collaborated on the study with a University of California-Berkeley scientist and two of his colleagues from the geography department at the University of Utah, to explain the alarming increases. Wildfire, he cautioned, is complicated.

“We see a lot of variability in fire, but this study makes it clear that the same areas that have had the largest increases in fire have also had increases in drought severity,” Dennison says. “While the time series is too short to absolutely blame climate change, it is striking that the trends in increased fire cross so many different regions of the West, and the changes are very consistent with what we know about climate change. Within some parts of the West, past fire suppression and invasive species are likely contributing, too.”

Officials have already taken note of the trend. It’s hard not to. State firefighting budgets are being stretched. The U.S. Forest Service has been borrowing more from other funds recently to meet spiraling firefighting costs.

Instead of merely dispatching a cartoon bear to tell people to be careful, governments are working closely with communities to help reduce wildfire’s rising risks—and to help them rebound after a blaze.

The National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy, published this month, covers 46 million homes and shirks a one-size-fits-all approach in favor of flexible approaches to maintaining fire-resilient landscapes, bracing communities for blazes, and helping governments decide when to desperately douse flames. Dennison’s findings could support this pliable approach.

“Fire has increased most in the southwest and mountain regions,” Dennison says. “That tells us where the biggest impacts of fire are occurring. It also tells us where the costs of fire are likely to be highest in the future.”