Twenty-six years ago this week, the Exxon Valdez, an oil tanker, ran aground on a reef in Alaska’s glacier-ringed Prince William Sound, spilling millions of gallons of oil. I had just turned seven, but I still remember seeing photos of oil-coated sea otters, birds, and seals. It would have been a disaster anywhere, but the spill’s remote, mountainous location, filled with photogenic wildlife, made it an especially memorable one.

At first I planned to devote my column this week to the lingering effects of the spill. But that was well covered by various outlets during last year’s 25th anniversary, so I decided instead to focus on another, neighboring region, just south of the Alaska panhandle—one where the oil tankers haven’t yet arrived.

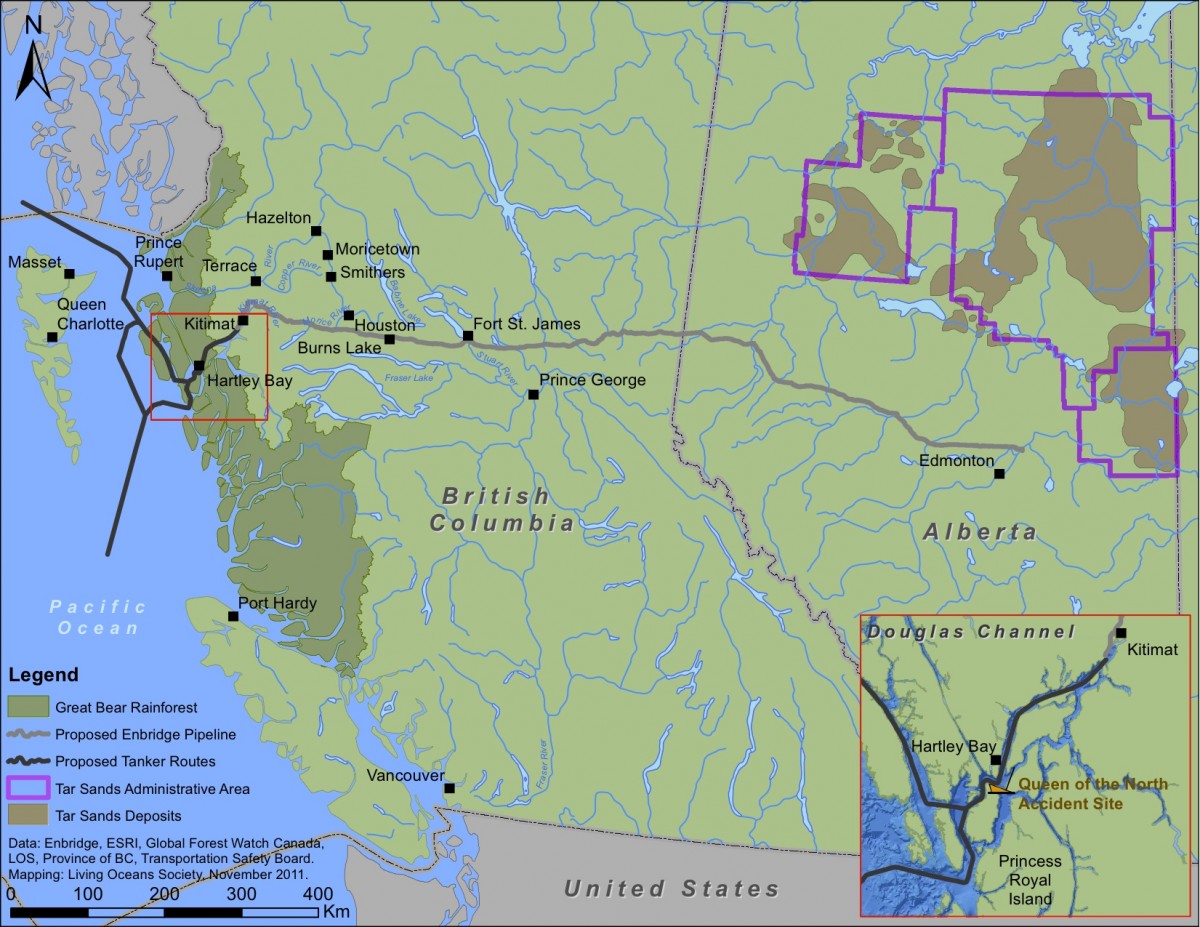

Keystone XL gets most of the press in the States, but in Canada a second proposed pipeline, Enbridge’s Northern Gateway, is at least as contentious. It would carry Alberta crude over the Rockies to the northern coast of British Columbia and the small port of Kitimat, where tankers would transport it out through the narrow, misty maze of the Inside Passage, around the Queen Charlotte Islands—more often known these days as Haida Gwaii—and across the Pacific to Asia.

Arno Kopecky, a journalist based in B.C.’s Lower Mainland, sailed the proposed Northern Gateway tanker route for his 2013 book, The Oil Man and the Sea. I called him to talk about why the tanker route makes some people so nervous.

The uproar, he says, goes beyond your basic NIMBYism—who, after all, wants an oil tanker route in their backyard? But the proposed Northern Gateway tanker route runs through an ecological region known as the Great Bear Rainforest, and it, for Kopecky, is too important to risk.

“There are some places in the world that are biological hotspots, and these places are vanishingly rare in today’s ocean environment,” he says. “It’s no secret that the oceans are taking massive hits.” Humpback whale populations have rebounded in the region, according to Kopecky. Herring populations—which still, further north, haven’t recovered from the Exxon Valdez spill—are going strong. Orcas and salmon are thriving too, and the salmon, in turn, feed land-based species like eagles and grizzlies, while their bodies fertilize the soil after each upriver journey.

“You have this really amphibious ecosystem where there’s no clear dividing line between ocean and land, and it is so bountiful that I always think of it as Canada’s Amazon of the north—it’s almost like an oceanic Serengeti,” Kopecky says. “It’s so teeming with wildlife that there’s almost nowhere like it in the world.”

So the region is a very bad place to have a spill. It’s also a risky place for shipping. In March 2006, the Queen of the North, a large car and passenger ferry in B.C.’s fleet, went down south of Prince Rupert, in the same waters that the tankers would pass through. Two passengers died, and the wreck was never recovered. Then, last October, a Russian cargo ship, the Simushir, lost power off the coast of Haida Gwaii and began drifting toward shore. It took multiple rescue ships multiple attempts to tow the ship safely away from the islands’ coastline.

“There are some places in the world that are biological hotspots, and these places are vanishingly rare in today’s ocean environment. It’s no secret that the oceans are taking massive hits.”

“When things go wrong at sea they go wrong all at once,” Kopecky says, “and really quickly.” Still, the concerns his reporting in the region has left him with aren’t all about a worst-case scenario.

“Even without a major tanker spill or without an accident, this sort of oceanic ecosystem is not compatible, in its present state, with high-volume oil tanker traffic,” Kopecky says. “There’s just no way that that number of humpback whales and orca whales and all these other species would be able to exist in their current abundance with a whole lot of oil tanker traffic.”

Happily for Kopecky and Northern Gateway’s opponents, the pipeline and tanker route are currently in limbo indefinitely. More than a half-dozen First Nations lawsuits targeting both the pipeline and the proposed tanker route are working their slow way through the courts, and as a result—although the project has received approval from Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s government—there is no firm date for the start of construction. Canada’s looming federal election could play a role too: Both major opposition leaders have said they’d kill the project if they win power later this year.

For Kopecky, his concerns aren’t about a blanket resistance to development, they’re about picking locations where there is less at stake. “It’s not a question of, are we going to have industrial development or are we not going to have industrial development? It’s a question of, where are we going to do it and how much are we going to do it? And,” he says, borrowing a phrase from author Wade Davis, “you wouldn’t drill for oil in the Sistine Chapel.”

Dispatches From a Changing Arctic is a biweekly series of reported stories from Alaska and the three Canadian northern territories.