Early Years

Stevenson grew up in rural Delaware, where playgrounds and pools remained segregated into the 1960s, even after the schools were forcibly integrated. By age 10, Stevenson—a precocious piano player—was playing and touring with his church choir. His brother believes this gave Bryan confidence when performing before an audience, which he’s frequently had to do in front of judges and juries throughout his career as a lawyer.

Pivotal Moment

During his joint study at Harvard Law School and the Kennedy School of Government, Stevenson grew disillusioned with the coursework, which he saw as disconnected from the social issues that drove him toward law in the first place. This changed one December when he flew to Atlanta for an internship with the Southern Prisoners Defense Committee. The organization’s director, Stephen Bright, happened to be seated near Stevenson on the flight, and their conversation that day reinvigorated Stevenson’s excitement about lawyering in pursuit of justice.

Equal Justice

Alabama is the only death-penalty state in the country that doesn’t provide state-funded legal assistance to death-row prisoners. To address this inequity, Stevenson founded the Equal Justice Initiative in 1989, and remains its executive director. The Montgomery-based non-profit now has over 50 employees who work to fight poverty, provide policy recommendations to lawmakers, and represent death-row prisoners and juvenile offenders. When Congress cut aid to death-penalty defense organizations in the mid-1990s (a substantial portion of EJI’s funding at the time), Stevenson was able to keep the doors open by donating the entire $300,000 award from a MacArthur “genius” grant he won to EJI.

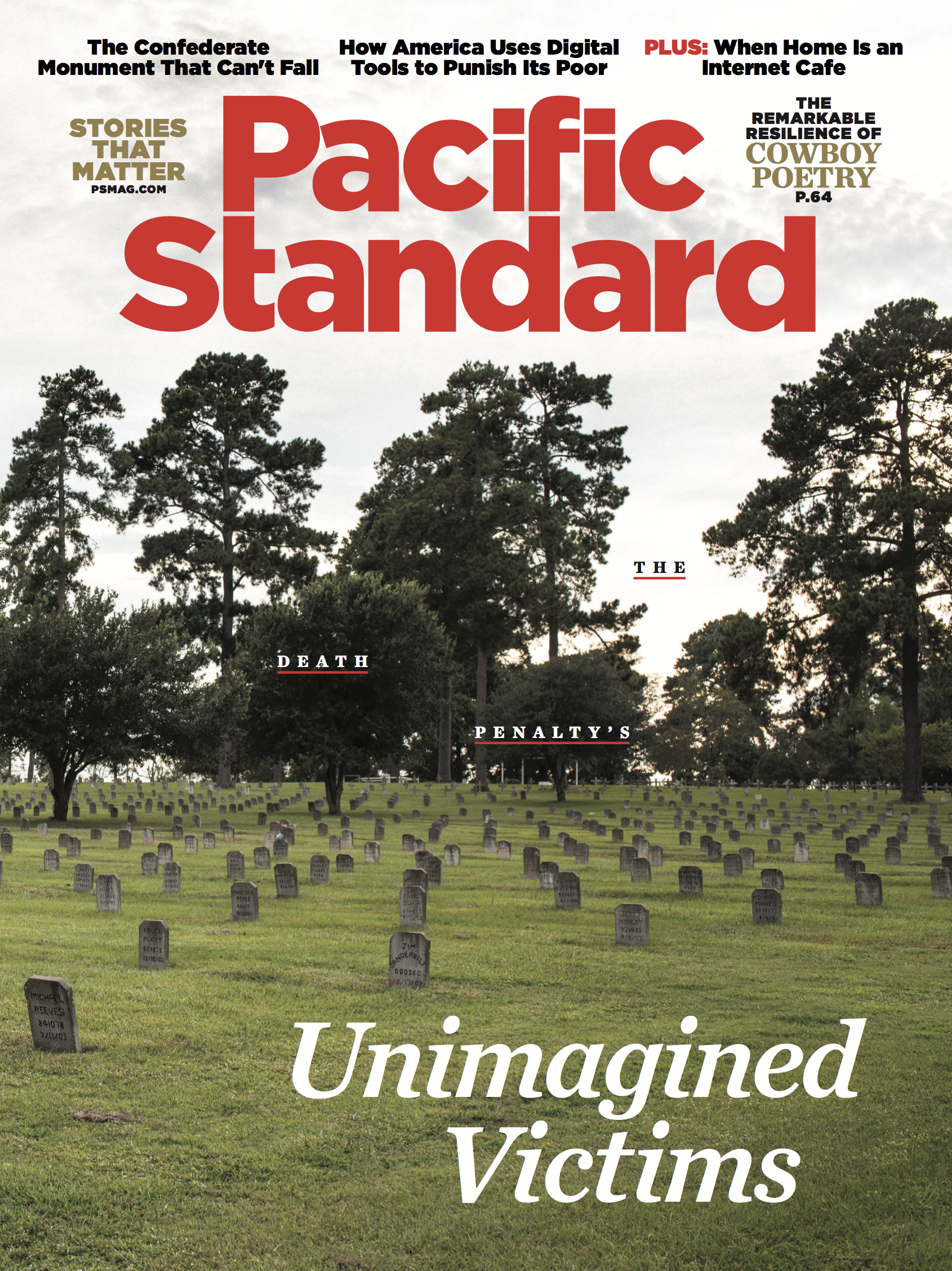

(Photo: Jerome Sessini/Magnum Photos)

Courtroom Triumphs

Stevenson has saved hundreds of prisoners from execution, including Anthony Ray Hinton, a death-row prisoner whose appeal went all the way to the Supreme Court, which ordered him a new trial. Hinton was then found not guilty and released, after nearly three decades of incarceration. Stevenson has argued before the Supreme Court five times, resulting in a string of decisions banning life-without-parole sentences for convicted minors. These rulings made possible resentencing hearings for as many as 2,300 previously sentenced people. Another of Stevenson’s hard-won cases resulted in a ruling that affirmed the right of death-row inmates to challenge the proposed method of their eventual execution.

Just Mercy

In 2014, Stevenson published Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption—part memoir, part treatise on some of the most egregious inequalities of our criminal justice system. The book weaves together the stories of several prominent legal cases, most of them involving the death penalty, solitary confinement, and harsh punishments given to minors. It received the 2015 Carnegie Medal for non-fiction, and as of press time had spent over 80 weeks on the New York Times Bestseller list.

Memorializing Terrorism

Between 1877 and 1950, over 4,000 black Americans were extrajudicially executed, acts that Stevenson unflinchingly calls “racial terrorism.” Yet no national monument existed to memorialize these victims. Later this year, EJI will open its National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery—800 hanging columns of oxidizing steel, one for every county across the United States where lynching took place during the Jim Crow era. EJI will also open The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration in a former slave warehouse nearby. One of the exhibits will feature hundreds of gallon-sized jugs, each filled with soil gathered from sites across the country where lynchings took place.

A version of this story originally appeared in the February 2018 issue of Pacific Standard as a sidebar to “Bryan Stevenson on What Well-Meaning White People Need to Know About Race.” Subscribe now and get eight issues/year or purchase a single copy of the magazine.