Editor’s Note: Read—and share—this story in Spanish.

The puddles in the potholes were frozen solid the first time Sofia saw Fairmont City, Illinois. Ugly, she thought, as her father pulled off the main road just east of St. Louis into the wedge of bungalows and trucking yards that was supposed to be their new hometown. She and her parents had driven through the night from Arkansas to get here. Later they would sleep, and the next morning Sofia (whose name has been changed to protect her privacy) and her mother would wake up at 4 a.m. to stand on a packing line in a produce distribution warehouse pushing vegetables into cartons. The job was a godsend. It paid cash and didn’t require English or a work visa—neither of which she or her parents had. But, all the same, as Sofia drove into town that March morning, she felt a wave of sadness wash over her.

It was her second big move in four years. The first, when she was 16, had taken her family north from adobe village in central Mexico, by bus across hundreds of parched miles, and finally by boat over the Rio Grande under the eye of the coyote they’d hired to help them evade border police. The decision to leave had felt obvious: In the village, the family had scratched out a living growing corn and beans and washing clothes. There weren’t many other options. Every time someone in the village did manage to open a business, armed strongmen showed up demanding a cut. Half for us, half for you, they would say. So when two of Sofia’s aunts, who lived in Arkansas, suggested the family join them, they went.. Four years later, they were uprooting themselves again, for another unknown place.

As the years rolled on, Fairmont City became home. Sofia had two sons and got a better job at a restaurant. She bought a car. The little town of 2,600 grew on her. There was a Catholic church, a library with Spanish books, and a brick town hall that looked like a miniature castle. It felt safe. And just as her cousin had promised, it didn’t matter that neither she nor her parents spoke English or had legal immigration status. Whenever she needed information about navigating daily life—like how to sign her kids up for health insurance, or whether to open a bank account—she was able to ask a friend or find it herself in Spanish.

But six years into life in Fairmont City, there was still plenty she didn’t know about her new home.

She didn’t know that for 50 years a huge zinc plant had dominated the economy, and that, when it closed in 1967, it left behind a poisonous residue of lead, arsenic, cadmium, zinc, and manganese. She didn’t know that, behind a barbed-wire-topped fence three blocks from her home, 90 of the 132 acres of the former American Zinc smelter were littered with open piles of metal-laden slag, some of it ground to the consistency of talc powder. She didn’t know that many of the town’s alleyways and yards were filled with the same slag, or that more than two decades ago the government had deemed the contamination a health threat to residents.

On a December afternoon, as Sofia’s three-year-old son races around their living room shooting a toy bazooka, she says she’s never even heard about the pollution. Like her son, she has round cheeks and a bright smile. She speaks calmly. “It’s like people wanted to hide that. … I don’t think any of the immigrants living here know about it.”

We met Sofia while investigating two dozen places across the United States where lead, dioxin, mercury, and other extremely toxic substances pose a direct health threat to the people living nearby. Each of these sites is on the National Priorities List of the federal Superfund program, a billion-dollar initiative designed in 1980 to clean up the country’s most contaminated places. Each also sits in a neighborhood where an unusually large number of residents don’t speak English.

We identified these sites by analyzing data from the U.S. Census and the Environmental Protection Agency, which runs the Superfund program. In the most extreme case, 33 percent of people within a mile of the site live in homes where no adults speak English very well. At other locations, the figure is lower, but all have more of these so-called linguistically isolated households than three-quarters of American neighborhoods. The families in these households are at a unique disadvantage in obtaining information about environmental risks and fighting back against them. As immigrants, they are also much less likely than other Americans to have health insurance, and therefore to receive care for pollution-related problems.

Ensuring environmental justice for these communities is an official duty of the federal government. More than two decades ago, President Bill Clinton signed an executive order dictating that all federal agencies—including the EPA—protect poor and minority communities that face disproportionately higher rates of pollution. Immigrants are likely to fit both these categories: Half of all immigrants who arrived between 1965 and 2015 came from Latin America, and a quarter came from Asia. In 2010, nearly one in four of those from Latin America lived below the poverty line. According to another Clinton executive order, signed in 2000, the EPA and other agencies must also ensure people with limited English skills can access their services, and, under Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, they may not discriminate based on country of birth.

But the EPA certainly isn’t reaching residents like Sofia in Fairmont City. Across the county, the agency’s record of outreach is inconsistent at best. While it often provides information about Superfund sites in Spanish and other languages, it typically translates only the most basic documents, such as fact sheets and overviews. Residents of polluted neighborhoods describe years of delay, inaction, lack of transparency, and withheld information on the part of the feds. The current system rewards communities with strong activists but does little for residents who are fearful of communicating with a federal agency because of immigration status, are unaware of the extent of contamination, or don’t know that they should be organizing to begin with.

Government culture is part of the problem. A bigger part is a funding structure that—since the early 2000s—has relied on negotiations with recalcitrant polluters and budget infusions from Congress to keep the clean-ups going. Simply put, the EPA doesn’t have enough money to do the job right—and that was true even before the election of President Donald Trump and appointment of Scott Pruitt to head the agency. The situation only promises to worsen as the Trump administration increases scrutiny of immigrants, loosens environmental regulations, and threatens to cut the Superfund budget.

Eduardo Siqueira, a medical doctor and associate professor at the University of Massachusetts–Boston who works with the metro area’s Brazilian community, is among the many experts and advocates we spoke with who echoed those critiques. He says the EPA wasn’t even achieving environmental justice with communities that speak English. “Imagine when they have to deal with either lower-income Asian populations or lower-income Latino populations,” he says. “They are not equipped at all.”

The picture isn’t black and white, of course. In the past, the agency has forged strong relationships with immigrant communities in cities like New York, Boston, and Chicago, and some individual staff members take environmental equity seriously. In some places, like Newark, New Jersey’s Little Portugal, immigrants have led hard, public battles for those gains. Agency officials defend their record too. In an emailed statement in the final months of the Obama administration, they called their environmental justice work “robust and successful,” pointing to many new initiatives. (The current EPA administration did not respond to a request for comment.)

Yet independent reviews have often found otherwise—even before the political shift toward a less civil-rights-friendly administration. A 2015 Center for Public Integrity investigation revealed that the EPA’s Office of Civil Rights rejected or dismissed over 90 percent of Title VI complaints alleging environmental discrimination and hasn’t ever formally found a violation of the Civil Rights Act. In 2016, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights released a report that found the EPA had never found a violation of Clinton’s 1994 executive order and was not meeting its civil rights obligations. It also found that communities suffering from industrial pollution experienced extreme delays and inaction on the part of the agency. When faced with environmental justice concerns, the EPA “does not take action” until it is “forced to do so,” according to the report. When it does act, its staff members “make easy choices and outsource any environmental justice responsibilities onto others.”

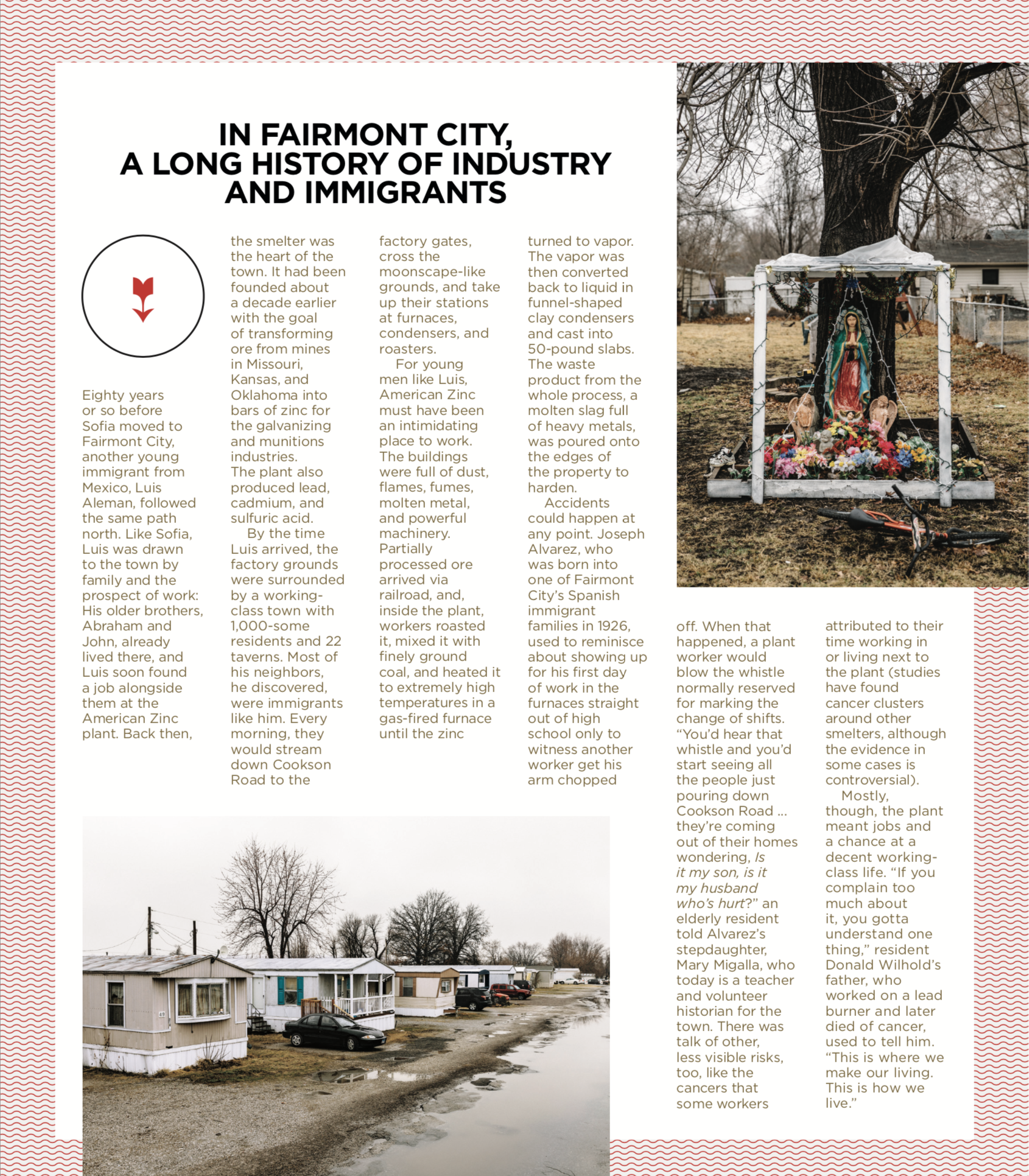

The wave of immigration that brought Sofia to Fairmont City started in the early 1990s, when Mexicans and Central Americans working in the scrapyards outside St. Louis began moving into the cheap, small homes left behind in the aftermath of the zinc smelter’s collapse. Right around the same time, the town began its epic tangle with the EPA over what to do about the pollution from the old plant.

Public concern started to rise in 1976, when a transportation company called XTRA Intermodal began leasing the defunct American Zinc property and turned it into a trucking terminal. At the time, an area the size of 11 football fields was covered in slag containing lead, which attacks the nervous system; arsenic, which causes cancer; and cadmium, which damages the kidneys and weakens bones. XTRA began grinding that material up and redistributing it to level other parts of the smelter grounds, which allowed wind and the constant truck traffic to whip it up into the air and carry it off the property.

“It was like living in a dust funnel,” says Kathy Wilhold, who lived directly outside the factory gates with her family in the 1980s. “I couldn’t breathe. I couldn’t go outside.”

(Photo: William Widmer)

(Photo: William Widmer)

(Photo: William Widmer)

Although residents didn’t give it much thought at the time, the nearby streets were already chock-full of the same slag. Decades earlier, the smelter had doled it out to the city and allegedly to anyone who wanted to fill in their yard, pave an alleyway, or sprinkle it on the streets to increase traction. Later, the EPA would determine that this—not the dust from the XTRA era—was how most of the contamination got from the plant to the neighborhoods surrounding it. (XTRA and Blue Tee, the successor to American Zinc, fought in court over the precise degree of responsibility each has for cleaning up the mess. In 2016 Gold Fields Mining, which had indemnified Blue Tee’s liability costs, filed for bankruptcy, and in 2017 Peabody Energy, which took on Gold Fields’ debt, reached a settlement with the EPA to contribute funding to the Fairmont clean-up. As of press time, XTRA had not responded to multiple requests for comment.)

It was outrage over XTRA’s dust clouds, though, that first pulled the EPA into Fairmont City. Wilhold and others spent years calling up local officials to complain about the choking particles that sometimes darkened the sky. Finally, in the early 1990s, the state EPA started an investigation.

Between 1994 and 1996, testing ordered by the state EPA had turned up heavy metal contamination in soil both on and off the old factory grounds at levels high enough to threaten the health of workers and children living nearby. Eight years later, Blue Tee dug up 152 properties contaminated with lead, including many residential yards. Instead of requiring Blue Tee to cart the soil out of town, however, the EPA allowed the company to dump it back on the factory grounds in a large open hill, surrounded by a soil berm and silt fencing. The risk assessment did not change, however, and 57 properties with lead levels high enough to require removal were not remediated (49—including a park across the street from Sofia’s home—were vacant lots, and eight were private properties whose owners denied permission for remediation). Town officials say that’s when their relations with the EPA soured.

“We couldn’t get an understanding of why, if this ground was so contaminated, they could just move it right back to the site, uncapped,” says Alex Bregan, who has been mayor of Fairmont City since 1996. Bregan was inundated with calls from angry, bewildered residents. Around six months later, he says, the EPA contacted him asking to sample the alleyways that run behind many of the houses, only a few of which had been tested. He refused.

“I wouldn’t let their people in the alleyways until they guaranteed that if they found anything they would take it out of the city,” he says. “They refused to do that, so I didn’t back down. I’m sure most of the alleyways are gonna glow. That stuff came right from the plant.”

In many communities, this is the sort of logjam that jolts residents into fighting back. Time tends to wrap sites like American Zinc in invisibility. When nothing is happening, people living around them worry about other things: putting food on the table, sending kids to school, paying for health care. Participation takes tremendous effort. As University of Kansas public policy researcher Dorothy Daley points out, people usually need a “focusing event” to draw their attention back to the site and spur them to activism—to hire lawyers, send petitions, and unearth old health reports. These are the actions that force the EPA to actually prioritize a National Priorities List site.

This is not what ultimately happened in Fairmont City. But it is exactly what happened 300 miles to the northeast last August in East Chicago, Indiana, another Superfund community with many immigrant residents.

In East Chicago, the focusing event came in the form of a letter written by Mayor Anthony Copeland to the 1,100 residents of the West Calumet Housing Complex. It announced that high levels of lead—higher even than those in Fairmont City—had been found in their yards and parks, and that hundreds of local children had been exposed to heavy metals for years. Government testing dating back to the mid-1980s confirms a long history of lead exposure in Calumet. But it wasn’t until Copeland sent his letter and ordered the demolition of the complex and the emergency relocation of everyone living in West Calumet that the extent of the contamination became clear to most residents. The mayor told them that, if they stayed in West Calumet, he couldn’t “tell you the irreparable damage that can happen to your child.”

Copeland’s letter bucked an official plan that the EPA outlined in 2012 (which he had publicly supported) and positioned the city in direct conflict with the agency. The EPA still believed that a clean-up was possible without forcing residents to leave, but, at the time of his announcement, an agency spokesperson said it respected that “[the mayor] wants to go a different way.” Copeland’s decision would impact thousands of lives.

The letter also attracted the attention of attorneys from the Shriver Center, a poverty-law group, who contacted the Environmental Advocacy Center at Northwestern School of Law. At the same time, with the extent of contamination now exposed, residents formed several groups, including Calumet Lives Matter and We the People for East Chicago, and then a few months later an advisory group to serve as a liaison to the EPA.

Driven in large part by pressure from this new coalition, resources and support began to flow into East Chicago. On the housing side, attorneys at the Shriver Center were able to pry loose millions of dollars from federal, state, and local housing agencies to cover moving expenses—although some residents say it’s not enough—and obtained a settlement in a civil rights complaint filed with the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The agreement provided extra time for residents to find housing. It also ensured that West Calumet residents who had been paying rent despite the pollution were excused from doing so until March 31, 2017. The EPA continued with its plan to sample and clean lead residue from 270 homes in West Calumet. With each test, the known extent of the contamination increased.

Copeland’s letter arrived seven years after the site had been added to the priority list—and a quarter century after it was initially proposed. Debbie Chizewer, an attorney representing East Chicago residents on multiple Superfund issues, says that, while the length of the clean-up in East Chicago “is not right,” it is typical, “although unfortunate for Superfund sites.”

The Superfund law works by forcing the company responsible for polluting a site to pay for its clean-up, to undertake the clean-up itself, or to retroactively pay for one the EPA conducted. In many cases, however, a responsible company either can’t be found or can’t pay because it went out of business, and the site becomes an “orphan.” To make up for this, lawmakers originally empowered the EPA to use money from a “polluter pays” tax on the petroleum and chemical industries to clean up the orphan sites. (The agency could still sue the individual companies later to recoup some of the costs.)

But in 1994 conservatives, led by Newt Gingrich and guided by his tax-slashing Republican Contract With America, swept into power. For the first time in 40 years, Republicans controlled both the House of Representatives and the Senate. The new leaders were more conservative than their predecessors. Some wanted complete Superfund repeal. Bob Dole, then Senate majority leader, called it—rather flatly—”a bad law.” Republicans allowed the “polluter pays” tax to expire after 1995, with $3.8 billion in the account.

The Superfund reserve dwindled, and any attempt to revive the tax was resisted by business and industry groups, including the American Petroleum Institute, the American Insurance Association, and the Business Roundtable. President George W. Bush refused to request its renewal in his 2003 budget and, by year’s end, the Superfund essentially ran out of cash.

(Photo: William Widmer)

(Photo: William Widmer)

Several lawmakers have tried and failed to revive the tax. Most notably, in 2009 Representative Earl Blumenauer, a Democrat from Oregon, proposed a bill to raise $18.9 billion over a decade by taxing the oil and chemical industries. President Barack Obama and EPA officials supported it. But fierce industry opposition and the potential for a Republican filibuster killed it. Charles Drevna, then president of the National Petrochemical and Refiners Association, told the Washington Post that policymakers had to stop using industry “as an ATM machine.”

Absent an industry tax, the EPA is left reliant mostly on taxpayer dollars and occasional agreements with polluting corporations. In 2013, the Superfund program had about half the money it did in 1999, and had finished fully remediating one-sixth the number of sites. Al Huang, who leads the Natural Resources Defense Council’s environmental justice team, says he’s seen deep-pocketed corporate giants like GE, Honeywell, and Occidental make calculated decisions to fight the clean-up law rather than comply. “They might spend millions of dollars doing studies and studies and studies and studies. That’s still cheaper than doing the clean-up itself,” he says.

Cheaper for companies, absolutely. But the costs to local communities can include depressed property values, stymied development, and uninsured families with expensive health problems. Many economic studies have found that homes near toxic waste sites tend to have lower value. Some have also found that, the longer a clean-up is delayed, the less likely it is that property values will rebound once the clean-up does happen. That’s because, according to one study author, stigma grows with time and media exposure, sometimes lingering even after the problem has been fixed.

Lagging clean-ups bring health problems, too, but very little data exists on their price tag for society. One study estimated that the health-care costs and value of lost work time from people getting sick from drinking water contaminated by volatile organic compounds at 258 Superfund sites added up to $330 million per year (in 1998 dollars; that’s around $500 million today). More recently, researchers found that clean-ups at Superfund sites in five large states between 1989 and 2003 lowered the frequency of birth defects among babies born nearby by 20 to 25 percent, although they didn’t translate that change into monetary savings.

In spite of this, it’s still hard to argue that the Superfund program is economically efficient. Cleaning up pollution is slow and expensive, and the return on investment can be murky. One widely cited study, for instance, put the median cost of averting a single case of cancer by cleaning up toxic waste at $388 million in 1999 dollars (around $570 million today). Yet these calculations are morally specious. Remediation may be pricey, but for the residents of these communities, decades-long delays bring nothing but downsides. As long as polluters can shirk their responsibility for cleaning up their own mess, the Superfund program—or something like it—is necessary to protect the natural rights of any person living in the U.S., even if it operates in the red.

Back in Fairmont City, residents never formed a citizen’s group. They never lobbied the government. They never had powerful attorneys from leading poverty and environmental clinics represent them. Instead, the community was left with Mayor Alex Bregan as its sole conduit to the EPA.

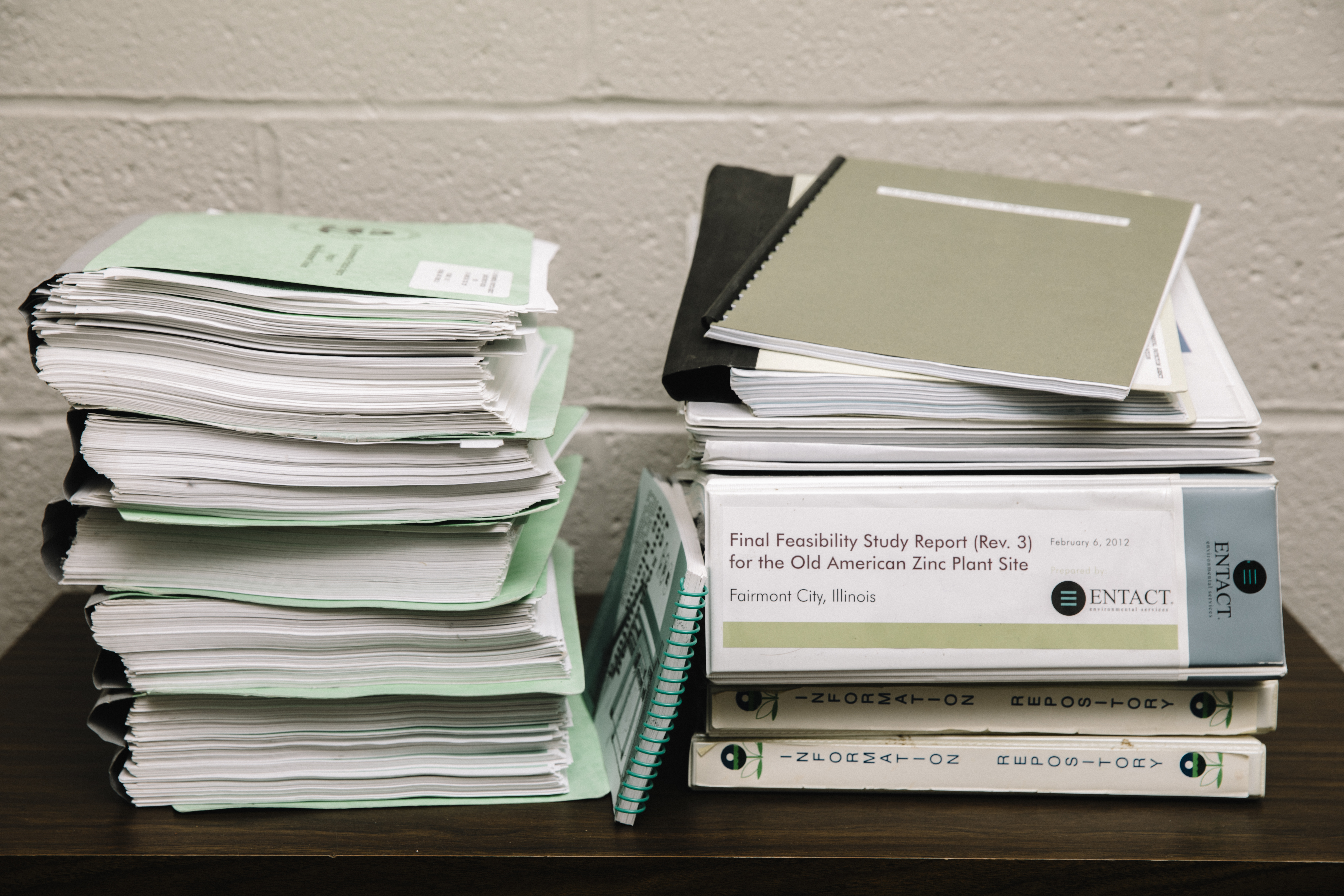

Initially, Bregan tried to push the EPA to remove the toxic slag from the town altogether, even bringing the city attorney in to negotiate. But he says the agency steamrolled him by bringing an overwhelming number of officials to the negotiations. By 2012, when the EPA was ready to present its final clean-up plan to the community, he says he’d given up on fighting back. “I certainly don’t have the means or really the will to take to court the EPA,” he told us by phone in 2016. “They’ll eat me alive.”

At the 2012 meeting, the EPA’s project manager, Sheila Desai, presented five main options for the clean-up. Both Desai, on behalf of the EPA, and Bregan argued in favor of the cheapest action option, which for a price tag of $11.4 million would consolidate the waste in a 35-acre hill in a corner of the old factory grounds and cover it with compacted soil (an approach some critics dub “pave and wave”). Desai said it would be a safe, realistic, and efficient solution, though many scientists question the feasibility of keeping caps intact over the long lifespan of the toxic materials contained beneath them, especially given that climate change will likely bring ever more severe flooding and storms. Some of the 25 or so residents in attendance wanted the waste removed altogether, which would have cost over 10 times as much. As one explained: “We went through this 10 years ago. And that was the biggest concern 10 years ago, that you didn’t remove it. You just moved it from one spot to the other … and that’s what’s bothering everyone in this place. … We’ve got a hazardous spot.”

Bregan, who had initially refused to even work with the agency unless it removed the slag, now urged his citizens to fold and accept the cheaper plan. When several people brought up health concerns, he shut them down, responding: “There is not a high level of cancer in this area and there are not kids walking around with six arms or anything.” On the phone, he suggested to us that these residents may have less than innocent motives: “Some people are gonna try to make a point of it to try to make money in suing ’em [the EPA].”

In fact, it’s impossible to know whether the contamination has caused health problems, because government agencies have only calculated risks based on contaminant levels—they haven’t studied residents’ health beyond one nearly 20-year-old study of children under the age of six. That is typical, in part because definitively linking health problems with specific sources of contamination is extremely difficult. But officials conducted targeted blood tests in East Chicago, and Philip Landrigan, an epidemiologist and pediatrician at Mt. Sinai, says targeted blood tests for exposure to lead in Fairmont City could help clarify whether it is causing problems there too.

“Lead can do serious damage to children, especially to their brains, at levels that are low enough that they produce no symptoms,” says Landrigan, whose groundbreaking research in the 1970s led the government to regulate lead in gasoline and paint. Children are particularly vulnerable because they play in and sometimes eat soil; their developing organs are highly susceptible to damage from chemicals; and, pound for pound, they take in more food, water, and air than adults do.

Landrigan says new research shows that even exposure to soil contaminated at 200 parts per million—half the EPA’s current level for taking action—is dangerous (the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, meanwhile, states that “no safe blood level in children has been identified”). Numerous residential properties in Fairmont City exceed that level, and surface slag on the site itself soars as high as 133,000 parts per million.

Today, an oddly muffled feeling pervades Fairmont. When we visit on a windy November day in 2016, numerous people tell us they never even think about the huge weed-and-slag-covered lot in the center of town. A priest shuts the door in our face when we ask him about it. Women working at a truck dispatch center outside the fence say they have no idea what’s happening with the clean-up on the other side.

Finances in Fairmont are tight. XTRA left in 2003 and the landfill that the town long depended on as a cash cow is now full. “This mayor’s interest is, OK, get this shit cleaned up the cheapest way you can so we can rent this property and get a tax base out of it,” says Donald Wilhold, Kathy’s husband. Bregan confirms this, more or less. “I want it cleaned and we can develop it,” he says when asked about his vision for the site. “It would become the most valuable piece of property in Fairmont City if it were clean.”

It’s hard to ignore the demographic changes that have transformed the town since the EPA first began investigating American Zinc’s legacy. In 1990, around a quarter of Fairmont City’s residents were Hispanic, and 7 percent were foreign born; today, over three-quarters are Hispanic, and 35 percent are foreign born.

One interpreter for the state of Illinois who makes home therapy visits to immigrant children in Fairmont City estimates that the majority of their parents are undocumented (she’s not allowed to ask, but the information usually seeps out over the course of relationships). She says she’s never encountered a family of two making more than $18,000, or one that knows about the Superfund clean-up. “They are just trying to make sure they can eat and have medical care,” she says. “Some of the people I work with are also illiterate. Political activity is a luxury.” The latter is certainly true for Sofia. She says she didn’t know about the EPA’s 2012 meeting, and that, even if she did, she would have stayed home out of fear of exposing her immigration status. “I’ve never gone [to a town meeting],” she says. “I feel like if you go to those you need to be an actual American person.”

While the EPA maintains that it has made every effort to reach out to the Spanish speakers in town, records show that outreach has been slow in coming. As early as the year 2000, EPA staff recognized that the demographic make-up of Fairmont City indicated “an [environmental justice] priority for the community around the site,” according to a memo. While interviewing residents 10 years later, officials were told that the “Hispanic population (the majority of the town) should be better targeted,” and materials and meetings should be translated into Spanish. The EPA says it sent out a postcard with a site status update in 2006, and in 2009 a Spanish-language letter warned parents to keep kids out of the dirt and cover exposed soil—information those families should have had more than a decade earlier.

If rhetoric is any indication, things are only likely to grow worse now that the federal government is controlled by President Donald Trump, who has ordered the construction of a border wall between Mexico and the U.S., and whose proposed 2018 budget cut the EPA’s allowance by 31 percent, including a 30 percent funding cut to the Superfund program and a 21 percent reduction in its staff. Initial proposals also called for eliminating the environmental justice office entirely, prompting its longtime director Mustafa Ali to resign in protest.

(Photo: William Widmer)

(Photo: William Widmer)

(Photo: William Widmer)

Contrary to all this, the new administrator has taken a marked interest in the Superfund program. Soon after assuming office, Pruitt visited the Calumet site in East Chicago to “show confidence to the people here in this community,” and in another speech he defended the Superfund program as “absolutely essential.” He also established a task force to “streamline” the program and reduce the length of clean-ups. Yet environmental advocates like University of Maryland law professor Rena Steinzor, who has worked on the Superfund law, remain suspicious. “He is engaged in a hostile takeover of that agency, and he does not believe in what it does. So why would he focus on the Superfund while accepting that the staff and budget are being cut?” she asks. “The answer, I think, is he wants to give corporations free passes on liability and clean-up standards and clear the National Priorities List.”

Ironically, only Congress—the body that has been so instrumental in undermining the Superfund program’s effectiveness—can restore its political independence by reinstating the “polluter pays” tax. A congressional subcommittee meeting in July of 2016 made it clear that representatives recognize that the program is failing: Fewer sites are being added and fewer still are being cleaned up. At the meeting, Democratic Congressman Frank Pallone said the expiration of the tax was the “main problem facing” the program, and EPA officials argued that reinstating it would break the logjam. A new bill was introduced in March of 2017, but there’s no sign that Congress intends to enact it.

So it seems the EPA will have to do its best with what it has—for now. And there is much the agency could do to improve its outreach to residents who don’t speak English, even with a limited budget. In Fairmont City, it could work with local organizations to reach marginalized residents, as its own plans recommend. Nationwide, it could make the best practices from places like Seattle and Newark—such as multilingual meetings, strong links to trusted community groups, and a steady presence in affected neighborhoods—standard procedure in any community with large numbers of non-English speakers.

Yet even the best outreach campaign runs the risk of missing marginalized residents like Sofia, who are deeply cautious of contact with government officials and their proxies. Once they do know about the pollution surrounding them, these residents may be unable or unwilling to fight for a fast, full clean-up.

Ultimately, the most fail-safe way to protect people is simply to clean up the places where they live—all of them, not just those where people are clamoring for action.

Last June in Fairmont City, the difficulty of achieving that goal was starkly apparent. A dozen or so state and federal officials sat behind folding tables in a blue community center one evening. The EPA was in town to answer questions from residents concerned about pollution and get approval to carry out a round of soil testing—testing that, somehow, over the past 25 years, had never been done. Bilingual mailers had been sent to over 800 households, and project managers were ramping up to go door-to-door collecting permission forms for testing on private property.

It was an informal open house, and over the course of two hours about 20 residents trickled in, milling around bird’s-eye photographs of the site and peppering the officials with concerns about cancer, clean-up costs, and contaminated dirt. About six were Spanish speakers who asked their questions through a Spanish-speaking EPA contractor. Many gave their permission for the tests.

(Photo: William Widmer)

At a table scattered with pamphlets on environmental health, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry employee Motria Caudill urged a middle-aged man in a black T-shirt and bandana to sign his permission form. He reeled off a list of health concerns, wondering if any were linked to the contamination.

“Health risks are much greater for children,” she told him. “As an adult, you don’t have to worry much. Plus, they’re going to clean it up.”

“But the damage has been done, right?” he replied. “We’ve been exposed for 27 years.”

Caudill was silent.

A version of this story originally appeared in the May 2018 issue of Pacific Standard. Subscribe now and get eight issues/year or purchase a single copy of the magazine. It was first published online on April 25th, 2018, exclusively for PS Premium members.