About halfway up the winding Generals Highway in Sequoia National Park, at an elevation of just over 4,000 feet there’s a nondescript pullout marked only by a sign that reads Big Fern Springs. Drive too fast and you’ll miss it entirely. On a warm January day last year, I pulled in, then set out from there with Noah Greenwald, a lanky environmentalist and wildlife advocate, in search of memories, footprints, and ghosts.

Below, a gray-brown haze hung over the flat expanse of the Central Valley like a lid. But up here the sky was a vibrant blue. The air smelled of soil and pine resin. A thousand feet above us, deep snows deposited during a record-breaking winter coated the famed groves of ancient sequoias and the high peaks beyond. But in the park’s lower reaches, the conditions were reminiscent of spring. Temperatures were in the mid-50s, and a small stream rushed down its steep bed through a mixed grove of oaks, sycamores, and sequoias.

(Photo: The Voorhes)

As Greenwald picked his way along a faint trail, he reached to the ground and retrieved a small broken limb. “White pine,” he said in a deliberate, slightly nasal tone as he raised the branch to eye-level. “Five needles per node.” From above came a raspy call. Greenwald’s head snapped skyward as he extended a finger toward the canopy: “Acorn woodpecker.” Below, he spotted a western gray squirrel. “Those aren’t your typical urban squirrels that you see people feeding in the park,” he said. “They’re hearty, and like to be left alone.”

This lovely if unremarkable glen happens to be a significant spot in California’s history. It was here, in 1924, where members of a road crew made the last reported sighting of a grizzly bear in California. (Two years earlier, the last wild grizzly killed by a human in California was shot not far from here, in a place called Horse Corral Meadow.) “You can see why a grizzly would have liked this spot,” said Greenwald, enthusiastically raking at the knobbly bark of an oak, to mimic the clawing action of a big bear. “There’s access to year-round water and game and plenty of acorns and chestnuts for food.”

But this was no lament for a vanished ecological past. Greenwald had brought me here to talk about the future of the grizzly in California.

An estimated 10,000 grizzly bears once inhabited the Golden State, from the high peaks of the Sierra to the shores of the Pacific Ocean. Today most of the roughly 1,500 grizzlies remaining in the Lower 48 are confined to parts of Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana, in an area comprising a mere 2 percent of their former range. They are remnants of the estimated 50,000 grizzlies that roamed the interior of the continental United States in the 1800s.

The California wilderness in the time of the grizzly must have been an imposing place. By all accounts, the California grizzly was significantly larger than its modern counterparts. Though historical estimates vary, anecdotal evidence suggests that a male California grizzly on its hind legs stood somewhere between seven and 10 feet tall and could tip the scales at well over 1,000 pounds. By comparison, the average weight of a male grizzly found in Yellowstone today is just over 400 pounds.

The size of California’s grizzlies was likely highly variable, however, and closely tied to habitat. For example, grizzlies that dwelled in the High Sierra (like extant bears in the Rocky and Cascade Mountains) had to contend with harsh, cold winters, and were likely much smaller than the state’s coast-dwelling bears, which did not hibernate and had year-round access to plentiful food sources. Those coastal bears not only could grow to huge physical proportions, but also achieve large population sizes. So plentiful were the animals in California’s Coast Ranges that they are said to have roamed in herds, fattening up on acorns, spawning salmon, and even dead marine mammals that washed up along the shore. One settler in the 1850s recounted seeing 40 bears in a single group along the Mattole River in Northern California.

The grizzly’s former ubiquity in California is reflected in its role in indigenous belief systems across the state. “The grizzly bear was looked upon by the valley Indians with superstitious awe, also by the coast Indians,” wrote noted California politician, pioneer, and author John Bidwell in the 1890s. In these legends, according to Bidwell, the bear is often a shape-shifter or a malign wanderer of the night. “They were said to be people,” he wrote, “but very bad people, and I have known Indians to claim that some of the old men could go in the night and talk with the bears.”

A number of tribes had religious practitioners called grizzly-shamans or bear-men. Among the Yokuts of central California, these bear-men performed evocative ceremonial dances. “They came to the public dances naked and painted black except for headbands of eagle down and necklaces of claws,” wrote Tracy Storer and Lloyd Tevis in their exhaustive 1955 classic California Grizzly. “[J]umping in short, stiff leaps to the rhythm of their growling song, they curved their fingers to look like the claws of grizzlies and finally leaped forward as if to seize a foe.“ The bear-men, the authors said, were believed to confer the power of reincarnation: “One who was killed and buried emerged from the ground in the form of a bear and walked away.” To the Nisenan tribe of Northern California, the grizzly was a werewolf-like figure that could be brought out by rubbing ceremonial herbs on the skin.

If the indigenous peoples of California viewed the grizzly with a kind of fearful reverence, Europeans saw them through an entirely different lens: one of hatred. Spanish soldiers at Mission Santa Cruz used the animals for target practice. Hundreds more were captured and then killed in bear-and-bull fights, which were held in Spanish settlements throughout California, including Monterey and San Francisco. This blood sport, said to have originated in Spain’s Pyrenees mountains, was a barbaric affair. Men on horseback equipped with lassos kept the bears from climbing the walls of the pit and attacking attendees. Once the grizzlies and bulls lost interest in attempting to maim their human captors, the animals would set upon one another with great ferocity. More often than not, the bear prevailed over the bull.

But there would be no prevailing over the rising human tide. By the end of the Mexican-American War and the cession of California to the U.S. in 1848, the persecution had intensified. Although grizzly attacks on humans were extremely rare, the animals became proficient killers of cattle, which became the dominant herbivore across much of California soon after the first Spanish missions were established in the 18th century. “Grizzlies usually were unable to capture the fleet-footed antelope, elk and deer which originally inhabited the range,” Storer and Tevis wrote in California Grizzly. Cattle were a different story altogether. “Domestic stock—even the half-wild breeds imported from Mexico—were so much less alert and swift than the native ungulates that they could probably be taken with relative ease.”

By merely being bears and exploiting an easily obtainable new food source, California’s grizzlies had run afoul of the livestock industry and dwellers of the state’s hinterlands. Spurred by gold fever and incentivized by $10 bounties, miners and ranchers wiped out staggering numbers of bears. According to Tevis and Storer, a San Luis Obispo hunter named Colin Preston reportedly killed 200 grizzlies in a single season in the 1840s. One hotel in the town of Mariposa, near Yosemite, served fried grizzly steaks for 75 cents. A famed trapper from Humboldt County named Seth Kinman became famous for cobbling surrealistic chairs from various grizzly bear parts—legs, claws, pelts, even snarling heads. Kinman presented one of his signature pieces of furniture as a gift to President Andrew Johnson in 1865. The slaughter was unrelenting and, in the end, absolute. Less than a century after California gained statehood in 1850, the California grizzly was no more than a memory.

And yet there is no doubt that the grizzly remains the apex species of the California imagination. The bear lopes across the state flag, and is the mascot of several state universities, the best known of which is University of California–Los Angeles’ smiling, lovable cartoon bruin, Joe. And though the grizzly bear no longer walks the land, it is ever-present on our maps. According to the U.S. Board on Geographic Names, more than 100 landforms across the state—mountains, creeks, and bays, among others—bear the name “grizzly.”

Nowadays, iconic predators seem to be having a sort of renaissance—both in the public imagination as well as in the wild—and California has been on the front lines of that rebirth. Wolves have found their way down from the Cascade Mountains in southern Oregon to the Siskiyou National Forest on California’s northern border. In 2016, a wolverine was seen near Lake Tahoe, only the second such sighting since the 1920s. And in recent years, a mountain lion called P-22 became a national celebrity after it was caught repeatedly by motion-activated trail cameras on a touristic circuit around Los Angeles, sauntering through Griffith Park and in front of the Hollywood sign.

Thus, it seemed as good a time as any to not just contemplate the tragic history of the California grizzly but also to discuss its future. And Noah Greenwald, perhaps more than anyone else, has been responsible for bringing reintroduction of the California grizzly into the current conversation.

This is not just theoretical posturing. Greenwald, who serves as endangered species director for the Center for Biological Diversity, is passionately interested in the following questions: Can the grizzly be restored to California? And if so, should it? To the first question, Greenwald believes the answer is a resounding yes. In 2014, the CBD filed a petition with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service asking the agency to revise its national recovery plan for grizzly bears to include California’s Sierra Nevada as an area for release. The CBD’s recommendations are based largely on the work of Carlos Carroll, a Northern California-based conservation biologist. According to an analysis by Carroll from 2001, a 2,355-square-mile section of prime habitat along the crest of the High Sierra could support a population of between 48 and 108 bears. “These are large areas with few roads and low [human] population density,” Greenwald said. “The southeastern reaches of the Sierra Nevada, in particular the Kern Plateau, is really good habitat.”

In addition to making management recommendations to wildlife agencies, Greenwald has mounted an aggressive public relations offensive on behalf of the bears. His work was highlighted in several major newspapers, and in 2014 he published an opinion piece in the Los Angeles Times. “There is no question,” Greenwald wrote, “that some will argue that California has too many people to support grizzly bears or that the bruins are simply too dangerous to bring back. But over the last several decades, we have learned much about how to live with these impressive animals. California has the space for bears and people.”

As of March, the CBD’s public petition to restore the bears had garnered nearly 20,000 signatures. “California is a state of big dreams, and it has really caught on,” Greenwald said.

The climate in Washington, D.C., however, is less receptive to big dreams, particularly when they relate to environmental issues. The Trump administration has expressed open hostility toward land conservation, and its proposed 2019 budget cuts all grant funding to states for endangered-species protection. Meanwhile, last summer, grizzly bears were delisted in Yellowstone after 42 years on the Endangered Species List. While the number of grizzlies in the greater Yellowstone region has increased more than four-fold, from 136 bears in 1975 to over 700 today, many wildlife biologists question whether that number represents a self-sustaining population. In the wake of the delisting by the Department of the Interior, state wildlife managers in Wyoming are now moving to reinstate a grizzly hunt.

For its part, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife has been firm in its opposition to reintroduction. Deputy Director of Communication Jordan Traverso has called spending time and money to study the issue a “non-starter.”

“We already have daily human-wildlife conflicts or interactions—black bears, mountain lions, coyotes,” she wrote in an email, explaining that reintroducing grizzlies “could exacerbate these problems, and potentially lead us into a place in which we’d have to dispatch them to protect human life or property.”

(Photo: The Voorhes)

Traverso, like other critics of grizzly reintroduction, points to a single figure: 39.5 million. That, of course, is the number of people presently residing in California, the country’s most populous state. The calculus is that the sheer number of people scattered across the landscape makes harmful, even fatal, interactions (for both bears and humans) inevitable. Critics also note that many of California’s coastal areas—once prime habitat for California’s grizzlies—are now built up with cities and towns. These urbanized areas present significant, even impenetrable, obstacles to large migrating mammals such as grizzly bears, which can roam across territories that span hundreds of square miles.

Other critics have resorted to more emotional appeals. In 2014, the Sacramento Bee published a series of letters received in response to a column by Mariel Garza about the pros and cons of reintroduction. Many comments landed on the con side of the issue (as did the column itself). Collectively they added up to a sort of grotesque composite. One letter referred to the bears as “super-predators.” Another asserted that the bruins are “unchallenged in the food chain, which includes humans.” One particularly strident response did not target grizzlies but the scientists proposing their restoration: “I’ve been hunted by a grizzly. Unlike their black bear cousins, these bears are territorial and a normal, healthy grizzly will kill you. … It’s moronic to even think a grizzly should reside in California anywhere outside of a zoo. Some of these biologists belong there as well.”

Greenwald confronts the anti-bear talking points head on, calmly, just as one is told to do upon encountering a grizzly in the backcountry. “Let’s start with population,” he said. “There are a lot of people, but the state’s population is concentrated in urban areas.” He notes that 26 million people—roughly two-thirds of California’s population—live in the coastal metropolises of San Diego, Los Angeles, and the San Francisco Bay Area.

Greenwald points out that millions of people visit Yellowstone National Park every year, and that human-bear incidents are tremendously low. In fact, over the park’s 146-year history, only eight people have been killed by bears (as of this writing). The Park Service has determined that, if visitors stick to the park’s “developed areas” along established trails and roads, the odds of getting attacked by a grizzly are about one in 25 million—about the same chance of a visitor getting hit by lightning. Humans, on the other hand, are undisputedly the greatest threat to bears. According to a joint study conducted by Canadian and American wildlife agencies, around 80 percent of the deaths of radio-collared bears in North America between 1975 and 1997 were caused by people.

This March, unexpected attention for grizzly bear recovery came from Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke, who visited North Cascades National Park headquarters to voice support for grizzly reintroduction there. In his speech, he referenced many of the same arguments as Greenwald does for bringing back what Zinke called the “great bear.” Environmentalists were shocked and a bit suspicious of the announcement.

But the science is compelling. Greenwald refers to a growing body of data showing that large predators such as grizzlies exert a powerful and beneficial top-down influence (known in science jargon as the “trophic cascade”) on ecosystems. For example, a grizzly reintroduction may actually reduce human-bear conflicts. This is not a contradiction, because black bears—not grizzlies—are the North American ursine species that tends to get into the most trouble with people, according to Greenwald. “Without grizzly bears, black bears have likely spread into niches they wouldn’t have otherwise occupied,” he said. He points out that the reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone unexpectedly bolstered fox populations, which had been severely suppressed by an overpopulation of coyotes. “There are unexpected interactions and trophic cascades from these reintroductions,” he said. “But you don’t really know what they are until you actually try it out.”

To imagine what a future California would be like with grizzly bears, one must look to the past—which is how I ended up in the archives of the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. Maureen “Moe” Flannery, the museum’s birds and mammals collection manager, and Jack Dumbacher, curator and chair of the California Academy’s Ornithology and Mammalogy department, led me through the museum’s labyrinthine interior, between dozens of rows of stark white cabinets punctuated by the occasional stuffed carcass of an animal peering out from a man-made perch.

We passed several rows then turned down one of them and stopped abruptly. Flannery motioned to a cabinet, which contained what looked like a greatest hits of American extinction. Inside lay the preserved bodies of two ivory-billed woodpeckers, thought to have gone extinct in its last known habitat in Louisiana in the 1940s (though several reported sightings in Florida and Arkansas suggest that a small population may still exist).

Flannery picked one up and held it delicately in her gloved hands. The preserved body was angular, almost spear-like. Beside the woodpeckers were a dozen or so vibrant green birds, their heads fringed in yellow and orange. These were the preserved remains of Carolina parakeets, a species of neo-tropical parrot that once inhabited old growth forests from New York to the Gulf of Mexico and all the way to eastern Colorado. The birds, declared extinct in 1939, were arrayed on their backs in a neat row, as one might organize ties in a drawer.

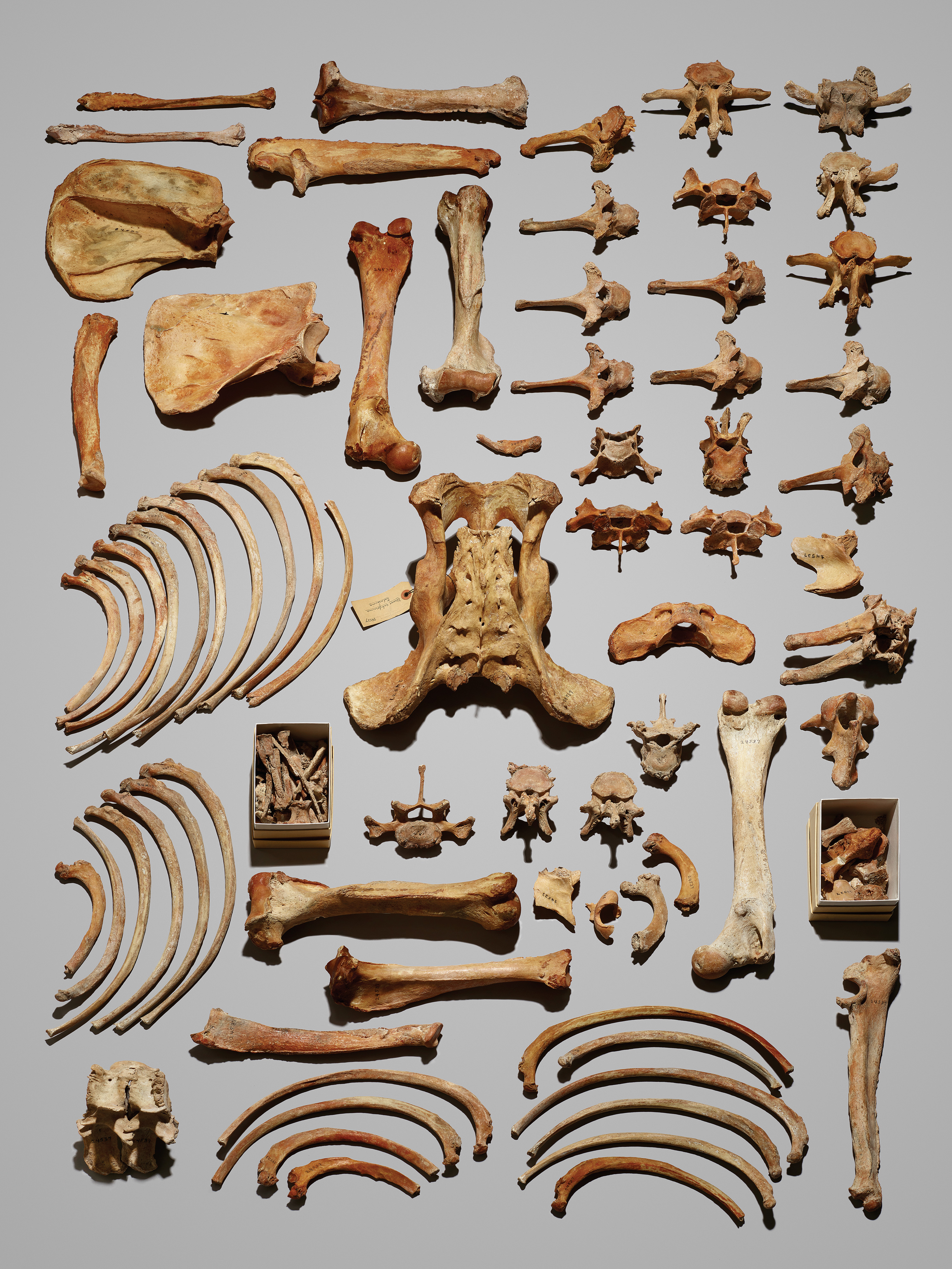

Next, Flannery picked up an oblong skull, tobacco-brown with age and flanged with massive canines. The teeth were set at an angle, with the lower canines positioned in front of the top ones. A tag affixed to the skull read, in a neat, antique script: No. 5567 Ursus Californicus Marina P.O. Monterey Co., California. The number indicates the order in which specimens were catalogued by the museum. This grizzly skull was acquired in 1926, I was told, two decades after the museum was destroyed by fire during the 1906 earthquake.

(Photo: The Voorhes)

Flannery carefully tucked the skull away and proceeded down another series of hallways into a refrigerated room known as the pelt room, where the air is kept at around 50 degrees Fahrenheit to protect the specimens stored within. On a set of shelves, a stuffed coyote, seal, and armadillo held vigil. Dumbacher noted that the mounted moose head on the wall just outside the room once graced San Francisco City Hall.

We then approached a wooden crate draped with opaque plastic. Inside was a large, indistinct brown mass. Flannery pulled back the plastic, noting the large, block-shaped head protruding from a set of broad, brown shoulders. The face was benign, slightly goofy even. Much of the fur around the snout had been rubbed away, the result of hundreds of curious hands stroking its muzzle during the years the stuffed animal was on public display in the nearby de Young Museum.

This is Monarch, surely the best-known California grizzly in the state, quite possibly the world. He is also the only known California grizzly mounted for public exhibit. Even though he is currently stowed out of view, Monarch’s likeness is seen by thousands every day—stalking over a mound of bright green grass, beneath a red star suspended in a pale white sky—on the California state flag.

It’s hard to imagine this animal, crated and stored unceremoniously like furniture, ranging across the wilds of southern California. It’s even harder when you consider the story, retold by Tevis and Storer, that Monarch was captured in what was little more than a journalistic stunt masterminded by newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. Hearst suspected that grizzlies were nearly extinct in California. So, in 1889, he enlisted a San Francisco Examiner reporter named Allen Kelly to try and find one. The intrepid if ill-prepared journalist staked out the mountains of Ventura County, near the town of Ojai, as well as the nearby Tehachapi Mountains. After five months in the backcountry, Kelly was running low on funds and still had not rustled up a wild bear. So, in order to appease his publisher, Kelly did the next best thing: He bought a male grizzly bear caught by trappers in the San Gabriel Mountains. That bear was Monarch. For almost 22 years, until his death in 1911, the male grizzly remained in captivity in the San Francisco Zoo. To the very end, Monarch remained stubborn, obstinate—wild. In his book Bears I Have Met—and Others, Kelly wrote, “He will fight anything from a crowbar to a powder magazine, and permit no man to handle him while he can move a muscle.”

Monarch’s remains changed hands several times before being acquired by the California Academy of Sciences in 1953, where his stuffed pelt has been permanently housed ever since (many of the bear’s bones are across town at the University of California–Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology).

Though Monarch is a symbol of a vanished ecological era, the grizzly’s remains could play a critical role in the bear’s future in the state. Monarch, it turns out, is one of the only California grizzly specimens from which DNA can be extracted.

Enter Beth Shapiro, a University of California–Santa Cruz biology professor, who is well known in rewilding circles, notably for her 2015 book How to Clone a Mammoth, which explores the science and thorny ethics of de-extinction: bringing extinct species back through various techniques such as cloning, genetic engineering, and selective breeding. Shapiro’s bear research has primarily focused on the effects of climate change on the genetic make-up of polar bears and grizzly bears in the Arctic. The two bears, it turns out, are very closely related and even capable of interbreeding and producing fertile cubs. Her work has revealed that, over the last 12,000 years, polar bears trapped on Alaskan islands have been “converted” into brown bears as they have come into contact with grizzlies dispersing from the Alaskan mainland.

Shapiro’s work mapping bear genes has drawn her into the vanished world of the California grizzly. In 2016, she and her research team took bone and tissue samples from Monarch. “We are trying to determine the unique genetic component of the California grizzly compared to other grizzly bears living in the Lower 48 states,” she said. “And also what that unique component meant in terms of the way this bear looked and acted.” Shapiro expects to find the telltale genetic signature of the polar bear in Monarch’s DNA. “It’s found in brown bears in the Lower 48 today,” she said. “And we anticipate that this will also be true for the California grizzly.”

But getting high-quality DNA from Monarch has proven a challenge. “We can get some really great data from 50,000-year-old mammoth bones frozen in permafrost,” she said. “But when an animal dies in a hot, wet place like California, the decay happens much more quickly.” In spite of Monarch’s degraded DNA, she said her team is using the genome of living bears as a sort of scaffold onto which the small fragments of genetic material can be grafted.

Shapiro is not only confident that Monarch’s genome will be mapped with precision, but that it will reveal a clear connection to extant populations of bears living today in Wyoming and Montana. “The genetics are going to show that this bear is very closely related to bears that currently live in other states,” she said, noting that grizzlies in the wild display tremendous variation in size, fur color, and overall visual appearance.

Because of these variations, it was once believed that the California grizzly was a distinct subspecies, Ursus arctos californicus. The notion was based largely on the work of an obsessive 19-century, Berkeley-based biologist named C. Hart Merriam. By examining the shapes and sizes of bear skulls collected from around the country, he posited that there were more than 80 variations of brown bears, many of which he believed to be unique species, in North America. (A well-known map published by Merriam proposed that California alone had six distinct subspecies of grizzly bears.) Today, however, scientists generally believe that the differences in skull shape and size observed by Merriam were the result not solely of genetic but also of environmental factors, namely climate and diet. Rather than dozens of subspecies, many zoologists now believe that only one species of brown bear roams—and for that matter has ever roamed—North America. And that bear is known simply as Ursus arctos.

Some have used the theory of the California grizzly being a separate subspecies to argue against reintroduction, suggesting that bears from the Intermountain West would not be able to adapt to the ecosystems of California. But that argument has been widely discredited.

(Photo: The Voorhes)

“There’s little doubt that the California grizzlies were specialized to do some things that were unique to habitats along the California coast,” Shapiro said. “But bears are very flexible behaviorally. And if you were to put bears back here I’m sure they would revert to doing some of the same things, and providing the same sort of ecosystem services, that California grizzly bears did.”

Jack Dumbacher is curious about the potential ecological effects of restoring grizzly bears to the Golden State. Back at the California Academy of Sciences, he gestured at the motionless Monarch. “A big grizzly like this could really change the structure of the natural communities that are out there,” he said. He recounts a conversation he’d had with members of the Hupa Tribe, in Northern California. “Grizzly bears will sometimes ring trees to sharpen their claws, and that can result in trees dying,” Dumbacher said. “Forest managers hate this because it’s viewed as an economic loss. But the tribe knows that those dead trees are important because that is where the pileated woodpecker nests.”

“A lot of our woodpeckers are in decline here in California,” Dumbacher said. “We think we’re mismanaging the forest, but maybe all we really need is the grizzly bear to set things straight again.”

I could almost see the bumper sticker: Want to Save a Woodpecker? Bring Back the Grizzly.

There has been an assumption, based largely on where grizzlies are found today—in isolated places like Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks and the remote Bob Marshall Wilderness—that if the bears belong anywhere in California it is in the remote high country in the Sierra Nevada or southern Cascades. But University of California–Santa Barbara researcher Peter Alagona has other ideas about what constitutes viable grizzly habitat. Alagona says that the grizzly was also known as the “chaparral bear” because it was found in greatest numbers not in California’s high country but in its Coast Ranges. In his 2013 book After the Grizzly, Alagona paints a vivid picture of these coastal bears: “Grizzlies scavenged the carcasses of beached marine mammals, grazed on perennial grasses and seeds, gathered berries, and foraged for fruits and nuts. They rooted around like pigs in search of roots and bulbs, and after the introduction of European hogs, the bears ate them too. At times and places of abundant food—such as along rivers during steelhead spawning seasons or in oak woodlands during acorn mast years—grizzlies congregated in large numbers. Such a varied and plentiful diet produced some enormous animals.”

In late March of 2017, Alagona and an interdisciplinary team of more than a dozen professors, lecturers, and graduate students made their first foray into the Sedgwick Reserve, a roughly 6,000-acre parcel of open space an hour north of Santa Barbara that is owned and managed by the University of California. The rolling hills were green, and bloomed with a colorful assortment of flowers. To the south, over a series of undulating hillsides, lay the Pacific Ocean. Beyond the property’s northwest boundary lay the former Neverland Ranch, the infamous estate of the late Michael Jackson.

Known as the California Grizzly Study Group, the team’s fieldwork is focused on gaining a better understanding of how the California grizzly lived in these coastal regions before human interference. As it turns out, reconstructing the way of life of an absent omnivorous animal largely means reconstructing its diet. One common misunderstanding, says Alagona (the group’s head and founding member), is that grizzlies are bloodthirsty predators just waiting for a hiker to snack on. “The California grizzly was an omnivorous opportunist—it ate almost anything and everything that was available,” wrote Tevis and Storer in California Grizzly. “In this respect the big bear was something like the house rat, the domestic pig, and even modern man.”

The purpose of the Sedgwick outing was to collect samples of various plants, mushrooms, bulbs, and roots, which may have comprised much of the California grizzly’s diet. Armed with shovels, we plodded into a green meadow and dug up a dozen or so species of flowers such as soap lilies and blue dicks, many of which had large, nutrient-packed bulbs. In one copse, the team was hunched over and rooting in the leaf litter for morels, chanterelles, and other edible mushrooms. Further on, we came upon a towering oak with hundreds of holes drilled into its bark. Inside each was a neatly seated acorn—the unmistakable handiwork of an acorn woodpecker. (Acorns are high in fat and protein, and California’s coastal grizzlies may have relied on them for a significant proportion of their calories.) Alagona and two graduate students quickly set to extracting the nuts with a knife. Alagona grunted as he tried to pry the oblong seeds free from their woody enclosures with his fingertips. He asked if anyone had a pair of pliers, which another team member snapped out from a Leatherman tool. Alagona twisted each seed free and dropped them into a paper bag. “The birds might be a little upset with us, but it’s all in the name of science,” he said.

Once uprooted, unearthed, or pried loose, each botanical sample was dropped into a paper bag, which was then marked with its scientific name, date, and place of origin. The samples would be taken to a lab, where researchers would look for molecular isotopes in bear bone and hair samples that match those found in the plant material. (Bones accumulate telltale compounds found in the foods animals eat throughout their lifetimes; hair and fur samples, on the other hand, give a far shorter-term snapshot, typically on the scale of a year or so.)

Counterintuitive as it seems, Alagona said, grizzlies probably exerted just as much influence on California’s plants as on its plant eaters. Their powerful fore-claws are just as useful for ripping at bark or tearing at the ground for grubs, mushrooms, and insects as they are for killing prey. In other words, the California grizzly acted as a kind of living plow, ripping and turning the soil and distributing seeds as it went. The loss of those ecosystem services may help explain why the composition of plants found in the coastal California landscape today is far different from what it was a century ago.

(Photo: The Voorhes)

We continued upward, to a ridgeline covered in a vibrant green rock called serpentinite. Below us unfolded a pastoral landscape of orchards and vine-stitched hillsides with small towns and farmhouses tucked between. The scenery was of a distinctly Mediterranean cast, which may explain our conversation’s turn toward Europe. There, Alagona noted, European brown bears (European cousins of the American grizzly) have recovered in areas very close to cities, including in Abruzzo National Park, only two hours by car from downtown Rome—closer than we were to downtown Los Angeles.

Demographic shifts and social changes have also played a key role in the brown bear’s resurgence overseas. “One of the reasons you have predators coming back to Europe—wolves, bears, lynx, and wolverines—is partly because Europe has become more urbanized, and parts of the countryside are emptying out,” Alagona said. “You also have a change in thinking and attitudes. People are imagining different futures, which is also vitally important.”

Alagona gestured to the high peaks of the Dick Smith and Sespe wilderness areas, rising to over 7,000 feet. He noted that, even in these wilderness areas—which are small by U.S. standards—one can find more continuous, roadless “wild” land than nearly anywhere in Europe. “When the Europeans look at our situation here, they think we have an ungodly amount of space. They are working in a completely different model,” he said, ticking off the essential differences on his fingers: Lots of people. Smaller land area. No wilderness. More bears.

In the U.S., we tend to operate in an either-or paradigm when it comes to conservation. And this historically has been a key stumbling block for the restoration of many large American mammals, including grizzly bears. Alagona points to the Central Valley, which has been transformed almost entirely into an unbroken industrial-scale agricultural landscape. And then there are the wilderness areas of the Sierra, which are off limits to all development. It is this bifurcation, he says, that has greatly influenced our thinking about what belongs where, what is “wild” and “not wild.” “We tend to think that animals belong in wilderness,” he said.

Europeans, on the other hand, have a less doctrinaire way of categorizing landscapes and, consequently, a more fluid way of looking at what constitutes habitat. “The Europeans are working to create more nature reserves, but they are limited in what they can do,” Alagona said. “And so, by definition, conservation has to occur in these human-dominated landscapes.”

Alagona believes that the rising number of large mammals in Europe is quickly dispelling a powerful myth: that bears and people cannot co-exist in close proximity. “It’s easy to imagine the risks, but it’s harder for people to imagine the benefits,” he said. “If grizzlies were to come back to California, then it would really be about educating people about what these animals are—and dispelling them of the notion that they are either teddy bears or monsters.”

Perhaps I had taken Alagona a bit too literally, but a couple weeks later, in keeping with the theme of imagination, I decided to venture into the backcountry of the Sespe Wilderness near Ojai, not far from where Allen Kelly hunted for grizzly bears, and where Monarch may have roamed in his lifetime. And because the future was our vantage, I thought it appropriate to bring my eight-year-old son, Owen, along. Through his eyes, I hoped to get a glimpse of this different future of which Alagona spoke.

Our plan was to walk a little-used path called the Chorro Grande Trail to a ridgeline just under the summit of 7,514-foot Reyes Peak. The trail, which gains about 3,000 vertical feet over seven miles, would take us through a cross-section of chaparral, oak woodland, and mixed oak-conifer forest—all of it once prime California grizzly habitat.

We parked along the shoulder of Highway 33, loaded our packs, and set off through a zone of cream-colored sandstone and wildfire-scorched chaparral. The trail continued gently upward. Eventually we came out of the burned trees and entered a narrow valley filled with large, mature oaks and Coulter pines. We decided it was a good place to stop and camp. A steep hillside covered in pale white shale cascaded down to our campsite, tucked under the sprawling limbs of a massive oak. With its mix of towering oaks and conifers, the place had a similar feel to Big Fern Springs.

As Owen climbed up and slid down the shale slide and built bridges in the little creek, I set up our tent and cook camp. An influential study I’d read by famed grizzly researchers Lance Craighead and Ernie Vyse suddenly came to mind, which posited that isolated populations of grizzlies (that is, bears disconnected via natural corridors to other populations) needed about 1,000 animals in order to ensure long-term survival.

A thousand bears, I thought, as I looked around the inviting glen, as quintessential a Coast Range landscape as they come. Perhaps there had been that many grizzlies here before.

As a thought experiment, I wondered how the campsite would “feel” knowing that a 1,000-pound animal could be foraging nearby. What would I be doing differently? Having camped and backpacked numerous times in Wyoming grizzly country, I knew this largely meant keeping a clean camp. Which is to say, I would not be cooking dinner where I was now, within a stone’s throw of our tent. Camping with grizzlies, above all, means greater respect for one’s surroundings, and greater attention to one’s own actions.

A few hours later, as the sun descended, the wind picked up and the moon cast eerie shadows through the tangled limbs of the live oaks and onto our tent. Ensconced in his mummy bag, my son pressed me with questions about California’s bears.

“Would we camp here if there were grizzlies, dad?” he asked.

“Yes,” I replied. “You just have to be smart about it. Keep a clean camp. Hang your food high in a tree. Never store food in your tent.”

“We never do that anyway,” he replied dismissively. “Who keeps food in their tent?”

Then he noted something that had slipped my attention. “But the creek, dad,” he said.

“What about it?”

“Bears get thirsty, right?” he asked, as if the implications were obvious.

“Yes,” I replied.

“Well, that’s the only water I’ve seen,” he said. “Don’t you think they might come here looking for a drink?”

(Photo: The Voorhes)

He had a point. Collectively, the Dick Smith, Sespe, Chumash, and San Rafael wildernesses, along with several other roadless stretches of the Los Padres National Forest, comprise around 630,000 acres, an area about half the size of Delaware. And yet, the area is conspicuously devoid of surface water. I wondered if a self-sustaining population of bears could inhabit this area of intermittent streams and soaring summer temperatures, particularly in an era of climate change and mounting ecological instability. Are these dry mountains poised to become even drier—and would that, in turn, mean fewer resources and more human-bear conflicts?

As Alagona said, it was easier to imagine the risks than the rewards. Any discussion of grizzly reintroduction is moot, he said, until we recognize that a reintroduction of this sort is not really about animal management but people management. “It’s not really clear whether having more bears in the world is actually good for bears, or whether it results in an increase in, say, ‘bear happiness,'” he said. “So if you can’t make that calculation, then you have to start looking at people—notably, what people want and what they are willing to risk or give up to have something else that is of value to them.”

That public reappraisal of the value of wildlife can happen—and sometimes very quickly. “When mountain lions started showing back up in Southern California in the 1980s and ’90s, people also freaked out,” Alagona said. “Now the mountain lion has become the mascot of Los Angeles.” He believes that the same might be true for the California grizzly. “If there was a way to fit these animals in,” he said, “then maybe a lot of other things that seemed impossible are possible.”

The next morning Owen and I rose at sun-up and plodded uptrail, toward the summit of Reyes Peak, which loomed 2,500 feet above. As we climbed the switchbacks, the full dimensions of the landscape became apparent below. Arid hillsides covered in chaparral and veined with arroyos ran in orderly rows toward the misty horizon. Plenty of space for a large omnivorous mammal to roam, it seemed.

In Spanish, Chorro Grande means “big flow.” But when we arrived at the trail’s namesake spring, it was dry. We plodded up one last steep section, through a stand of tall Ponderosa pines, before reaching the ridgeline. From the dry summit ridge, we could see the expanse of the Coast Range extending below us and, just beyond, the humped masses of the Channel Islands looming offshore. To the south, in the next valley, flowed Sespe Creek, one of the range’s permanent water sources and one of the last undammed waterways in Southern California. Just out of view, beyond the endless furrows of rolling ridgelines, lay the concrete wilderness of Los Angeles.

As I jotted notes, Owen sat on a large rock surveying the terrain through binoculars. “Dad, I can see bears up here,” he said matter-of-factly. I took him literally, and asked with slight concern if he’d spotted a black bear somewhere below us.

“No,” he said, smiling in the full California sun. “I mean someday. I think a grizzly would like it here.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the June/July 2018 issue of Pacific Standard. Subscribe now and get eight issues/year or purchase a single copy of the magazine. It was first published online on May 30th, 2018, exclusively for PS Premium members.