Valentina, a chubby 17-year-old wearing hot-pink spandex shorts, pink Converse, pigtails, and heavy eyeliner, sat on a cement bench in the back of a courtyard, hunched over a cell phone she had half-concealed between her knees. The sounds of traffic, birds trilling, and the music of street vendors carried over the wall rimmed with razor wire.

“I’m in for extortion,” she told me, licking a bright blue ice cream cone.

She was sentenced to 10 years at the Centro de Inserción Social Femenino, a Salvadoran prison for girls. “But my lawyer says if I’m good, I’ll only get four.” She was from Santa Tecla, a relatively safe and trendy town on the outskirts of San Salvador.

“You know Paseo del Carmen?” she asked excitedly, referring to the bustling strip of locally owned shops, bars, and restaurants. “That was my territory!”

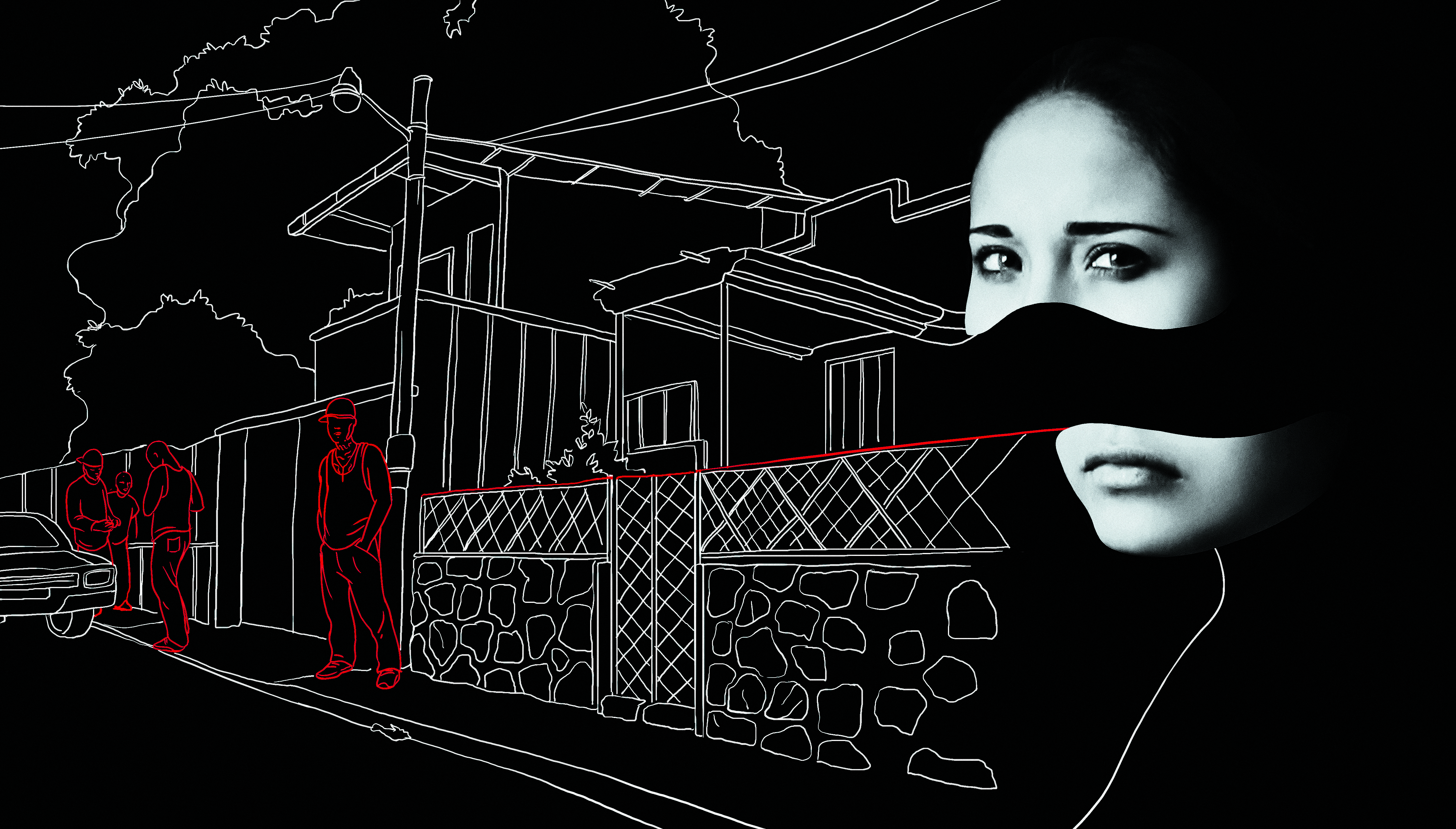

Valentina’s job for a local gang chapter had been to go door to door collecting renta, the bi-weekly “tax” imposed on businesses and sometimes individuals. “The problem is that, in Santa Tecla, they have cameras.” She shrugged.

Today was visitor’s day, and the young inmates, having been charged with such crimes as robbery, extortion, prostitution, drug trafficking, and murder, were all dolled up, hoping someone on their list would show up. They’d donned their best outfits, brushed their hair, and applied make-up, using one another as mirrors, as if going to a dance or a day out on the town. “Do you think there’ll be any boys?” one asked. They fell into giggles.

We were on the MS-13 side of the prison—all Salvadoran prisons are divided to keep rival gangs apart.

A guard offered a ball to a group of inmates, and a few girls (what else was there to do?) began playing on a mottled, patchy field of overgrown grass. The girls congregating outside were lower down in the gang pecking order. The higher-ups remained upstairs in the dark, 80-bed dormitory, keeping watch on the activity down below.

At the edge of the field, a girl named Dalia explained that she was in for drug trafficking. She’d fallen in with a crowd of low-level gangsters in her hometown. “We became really good friends, a great friendship. And they started to ask me to do things, little things,” she said. “They were my friends—I didn’t want to say no to them.” Sometimes when people said no, they’d get beaten up. But, she insisted, she wasn’t forced to do what she’d done.

Unless, that is, you consider the force of the larger circumstances: the lack of socioeconomic options for poor youth in El Salvador, the pervasive violence against women, and the near total impunity for such crimes.

In 2015, the government of El Salvador registered 575 femicides—the gender-motivated killing of women. It was the country’s second-highest femicide rate in 15 years (2011 was the highest). Approximately 45 percent of the murdered women were under the age of 30, and of those, 34 percent were under the age of 18. According to a report from the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies at the University of California–Hastings Law School, not only are Central America’s femicides “widespread, but they are carried out with horrific brutality…. Bodies generally appear burned, with hands and feet bound. Some have been beheaded, and autopsies reveal that the majority of the victims suffer torture and sexual abuse before dying.”

More than three-quarters of femicides in El Salvador are never prosecuted. As femicide rates have risen over the past decade, so has the number of young women and girls entering gang life. That fact can be attributed, in part, to the extraordinary growth of the gangs themselves, but it also reflects a survival instinct: Girls are increasingly joining gangs in order to protect themselves and their loved ones. Valentina and Dalia are among the tens of thousands of girls who have become involved in El Salvador’s strengthening organized-crime rings, either as full-fledged members, as girlfriends (sometimes by choice, often by force), or as loosely affiliated helpers (mothers and sisters, for example, who cook for the gangs). Since 2003, the government of El Salvador has attempted to crack down on gangs using La Mano Dura (Iron Fist) campaigns, but with minimal success. In early 2016, the government further militarized the country’s police force and expanded its power to arrest anyone on mere suspicion, turning the war on gangs into a seemingly perpetual arms race for control of Salvadoran society. Because adolescent boys fit the standard gangster profile, they are routinely targeted by authorities. Young women and girls can more easily slip by as they mule drugs or pick up bi-weekly extortion payments. Girls are assets to the gangs—inconspicuous foot soldiers, and excellent cannon fodder.

Trim and girlish, Dalia had a dark, mottled bruise on her bicep that appeared relatively fresh—the result of a game, she explained, that she and her inmate friends liked to play at night: They’d punch each other until one of them cried uncle. Did she win?

It looked like someone could topple Dalia with the slightest shove, but she stiffened at the question.

“Of course,” she said, stone-faced. She always won the punching game. Then she stood up and joined the players out on the raggedy field.

Valentina stowed her contraband cell phone and looked up at the field, where a group of visiting missionaries had begun playing soccer with the girls. Another 17-year-old inmate ran over to the bench and handed her baby to Valentina’s friend, then sprinted to the pitch, adjusting her floral bra, which peeked from beneath her shirt. At 18 months old, the boy had been living in this prison his whole life.

“Here, Papi!” Valentina said as she fed him a dollop of blue ice cream from her fingertip. Before long, visiting hours would be over, the field empty, and the girls back upstairs in the dark confines of the dormitory.

To become a full-fledged gang member in El Salvador, a young man often has to endure a severe beating, and is sometimes required to kill someone as an initiation rite. Women, however, are often initiated through either a similar beating, or through rape. Some have a choice, but most don’t.

“If you were cute, probably you’d be raped,” said 30-year-old Elena Guzman. “Or if the head of the gang said, ‘No, this is only for me,’ she’d become his girlfriend,” and that would be that.

Elena had managed to avoid any kind of initiation, having fallen into the gang life almost by accident. At the age of 15, she’d begun buying marijuana from the gang hub a few blocks away from her house, and within a few years she was selling drugs for the local MS-13 clica and staying up late to cut coke and bag weed.

She loved the way getting high made her feel—strong, confident, the edges worn down. For her, it was “a coping mechanism,” she explained, to deal with the challenges at home. Her family life was slowly unraveling: Her father had gone far into debt in the family business and had grown deeply depressed; her mother had left for the United States—El Norte, as it’s called in El Salvador, the North—to send money back in an effort to save the family; her older siblings were practically raising her, while simultaneously managing their own adolescent challenges.

Elena ran with a cool, alternative crowd of party kids, a relative social minority in El Salvador. She and her friends were always struggling to find weed on the street. Buying in bulk, she realized, would be cheaper, would make the stash last longer, and would also make her more popular among her friends. So one day she asked the tweaked-out neighborhood guy she usually bought from if he would take her to the headquarters so she could buy a larger quantity—a risky move, she knew, but one that played to her streak of recklessness and aspirational bravado.

He took her to the “destroyer house,” a small two-room structure where gang members congregated, nestled between the slums and her reasonably well-off San Salvador suburb. As Elena described it, “If you don’t have a place to go to sleep, that’s where you’re going to go—if you don’t have a place to take your girl, or to rape, that’s where you go. That’s where they keep the drugs and that’s where they keep the guns.”

She was scared, but cloaked herself in a mantle of outer toughness, projecting power with a sparkle of risk. She bought an ounce of weed and went back to her friends. When she showed them her score, their eyes bulged. She went back the next week for more.

After several months of feigning toughness as she exchanged money with the gang underlings, the tattooed MS-13 gang boss, who they called Smiley, noticed her. She could tell he was the boss from the way he was dressed—nice, well-pressed clothing, a collared shirt and baggy jeans, a baseball cap pulled down tight over his eyes so you could hardly see them—and by the way the others cowered a bit in his presence.

“Who are you selling to?” he demanded.

That he spoke to her at all was nerve-wracking, but that he was insinuating that she might be re-selling his stuff on his own turf was terrifying.

“No one,” she replied toughly. “I’m just buying this for my friends.”

He paused for a second.

“How many friends do you have?”

In Elena—this strange, alternative girl—Smiley saw a business opportunity.

For a couple years it went on like this, with Elena buying medium-sized quantities to sell to her friends, mixed in with the occasional load of coke for big party nights. She started scoring for her larger network of friends and acquaintances too. Soon, she was selling to the upper-middle-class alt-kid social scene at a mark-up and bringing Smiley back the profit. She was glad to do it; it curried favor with him, and she got to keep a cut. These favors, as she saw it then, kept her in the partying business, but of course also twined her more deeply to the crew at the destroyer house, where she was spending an increasing amount of time.

For years, Elena had also been going back and forth to the States on a tourist visa to visit her mom. Her English had become near-perfect (she spent time attending schools in Virginia, even though her visa prohibited it). This was post-9/11 U.S., and she’d heard that, even though she didn’t have permanent papers, if she enlisted in the army she would be allowed to stay in the U.S. to study once her military commitment was over (which, it turns out, is not true). But it sounded like a good deal to her—so, in 2004, she went back to El Salvador for what she thought would be the last time for many years.

“I came back to El Salvador and I started partying a lot,” she recalled. “Because, you know, I thought: ‘OK, fuck it, I’m not coming back. I’m not going to look at these people anymore, I don’t have anything to be scared of.'”

She was out practically every night, using harder and harder stuff. And she spent more time with Smiley and his crew. She decided to start selling in earnest to accrue more cash for her new life. She took on the street name of Lucia, and would sell to the rich kids at the underground techno parties that were being thrown all over San Salvador. It was fun—she was making money, running around town, swept up in the swagger and the rapturous late-night current of the city, and she had a purpose. Soon, she figured, she’d disappear from the scene altogether. It was a boon for Smiley as well: She was expanding his market, reaching people that his typical, lower-class drug-mule gangsters would never be able to reach, selling packets of pot and coke and ecstasy at double, triple, quadruple what they’d get on the neighborhood street corner.

“Sometimes I’d charge like five times as much just because I could,” she said. “And these fucking people were so grateful, they loved me, they’d be like, ‘Oh, Lucia, thank you, thank you!'”

By this time, she’d gotten pretty close with some of the guys at the destroyer house. She was an out lesbian, something of a rarity in El Salvador, particularly at that time, and certainly among the poorer classes where gangs proliferate. Though this fact about her had originally thrown the guys off when she’d first started coming around, they grew to see it as a curiosity, and Elena as a source of wisdom when it came to chicks. They could bitch about girls with her, and she’d commiserate and corroborate—”Yeah, bitches are crazy,” she’d agree—and they could also ask her for advice. She talked dirty with the guys, laughed big at their jokes, and told her own, getting stoned with them and partying late into the night. Smiley even began confiding in her, which placed her in somewhat of a position of honor.

He had a girlfriend for a while, and he would boast about her to Elena, and complain about her too. One day, the girlfriend had just stopped showing up. Where had she gone?

“She left,” Smiley had said with a shrug. “She went to El Norte.”

There were often women hanging around, but the women gang members were fewer in number, and they tended to work as mules or preparing the drugs for the boys (and Elena) to sell on the streets. Jessica, a girlfriend of one of the bosses, took Elena under her wing and taught her how to cut and weigh the coke. Jessica loved to drink Coca-Cola, and Elena would take her huge bottles of it that she’d glub down boisterously while showing Elena, who preferred beer, her tricks. Jessica had gotten out of prison, having taken the fall, as Elena understood it, for her ex-boyfriend’s crimes, and then, upon release, had gone right back to selling.

Elena hadn’t said goodbye to anyone in Smiley’s crew when she boarded the plane to go back to the States in 2007. But at the Miami airport, she was stopped by immigration. Something about her papers and her travel history looked suspicious, and the authorities discovered through a quick Internet search that she’d been violating the terms of her tourist visa by attending high school in the U.S. They sent her back to El Salvador, her plan of joining the army and an indefinite stay in El Norte dashed.

She quickly got a job at a call center making good money—she could speak English, after all. Each night after work, she went to the destroyer house.

The Salvadoran gang epidemic—which also afflicts neighboring Honduras and Guatemala—is, ironically, a product of El Norte, having sprung up in the wake of El Salvador’s brutal civil war in the 1980s. Leftist guerilla revolutionaries had been fighting the conservative government, which was effectively an oligarchy run by a handful of high-powered, wealthy families and geared toward their financial interests. The U.S., to prevent the spread of communism, funded and trained the government forces, which in turn perpetrated horrific crimes and massacres to try to tamp down the revolutionaries. Hundreds of thousands of people fled the violence in El Salvador—a country of around five million at the time. Most came to the U.S. as undocumented immigrants. In Los Angeles, gang activity was already prevalent, so young Salvadorans formed gangs of their own. When some of those undocumented gang members were arrested and deported, they brought the gangs home to El Salvador.

Today, the two most powerful gangs are Barrio 18, which has split into two rival factions, and MS-13, the gang into which Elena had fallen. (Both gangs continue to operate in the U.S., and both have expanded throughout the world, where, though largely decentralized, they appear to be growing in ranks and power.)

In the 13 years since Elena began selling for MS-13, gang violence in El Salvador has spiraled out of control. In 2015, 103 out of every 100,000 people in El Salvador were murdered—almost 20 times the 2014 global average, which was 5.3 murders per 100,000 people, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. In 2016 the homicide rate in El Salvador decreased, as the government ramped up its security (including implementing a few extrajudicial massacres of alleged gangsters) and gangs tried to broker a renewed deal with the government, but, at 80 homicides out of 100,000, it is still one of the highest in the world. The vast majority of killings are related to the gang wars. In July of 2015, the Salvadoran government estimated that somewhere between 500,000 and 600,000 Salvadorans were gang members—roughly 10 percent of the overall population—a figure that does not include the gangsters’ family members, partners, or children.

The economy in El Salvador relies heavily on remittances from abroad, and there are limited education opportunities and scant job options for youth. This has led troves of young people to join the gangs, and the high number of recruits has strengthened the organized crime rings, making them bigger, stronger, and more brutal. Most regions in El Salvador are now run by one of the gangs, and invisible but well-known lines are drawn through communities to delineate which gangs control what neighborhoods. To cross from one gang zone into another can often mean death.

“This is one of the most dangerous places in the world,” explained Silvia Juarez, advocate and researcher at ORMUSA, the Organization de Mujeres Salvadorena por la Paz (Salvadoran Women’s Organization for Peace), “but no one recognizes that we are in a war, because, of course, we’re not in a typical war.”

In a patriarchal society increasingly controlled by violent, male-dominated organized crime groups, rape, domestic violence, and the murder of women have become commonplace. (While the number of murders in El Salvador decreased in 2016, the number of reported rapes increased.) In 2011, according to the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies of the UC–Hastings School in San Francisco, California, El Salvador had the highest rate of femicide in the world. In the first three months of 2016, the Salvadoran National Police registered 197 femicides—more than double the number for the same period during the previous year. Meanwhile, gang members in El Salvador reserve the right to claim any girl in the neighborhood as their girlfriend, threatening her or her family with physical harm if she refuses to comply. Then there are the mothers, sisters, aunts, grandmothers, and spouses of gang members, who wash their clothes, cook their food, keep their houses, and who are, in effect, linked to the gangs often without meaning to be or asking to be, Juarez explains. Whether officially or unofficially linked to the gangs, women often receive a fraction, if any, of the payout. “Women take the same risks for crimes as the men do,” Juarez explains, “but they don’t receive the same revenue or benefit of the crime.”

It’s not as though men in gangs are getting rich either; most are looking to simply survive. As in most wars, it’s young men who are dying in the highest numbers. But also, as in most wars, women are experiencing horrific and under-recognized ripple effects of the violence: becoming victims of extortion, of rape, of forced “marriage,” and of murder.

Other statistics paint a stark picture for female Salvadorans. Girls and young women often get pregnant too young and out of wedlock. Nearly one-quarter of girls aged 15 to 19 have become pregnant at least once. A quarter of girls are married before they are 18, and abortion is illegal (women in El Salvador have even been jailed for having a miscarriage). Salvadoran girls attend school at approximately the same rates as boys, yet schooling in El Salvador is subpar for all, and more than 300,000 youth in El Salvador are currently out of school and without a job.

Joining a gang is one option for survival; another is to leave the country. Though historically it has been men who traveled to the U.S. to work and send money back to their families, today two of the largest demographics of migrants crossing into the U.S. are Central American women with young families and unaccompanied minors, an increasing number of whom are adolescent girls. In fiscal year 2016, 77,674 “family units”—groupings of parents and young children—were apprehended along the U.S. border with Mexico, a 500 percent increase from 2013. Before 2012, approximately 20 percent of unaccompanied minors taken into federal custody at the border each year were girls; that number grew to 27 percent in 2013, and to 33 percent in 2016. Girls face even greater risk than boys on their dangerous journeys to the U.S. “Girls know that they are likely to be raped on their way north,” Violeta Discua, a paralegal working with unaccompanied minors in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, told me. “So they take the pill or get a birth-control shot so that, if they are raped, they won’t get pregnant.” As Ana Solórzano, the director of the Migrant Return Center in San Salvador, put it, “The girls think that rape is just part of the cost of going north.” Worth the risk, in the minds of some, to escape the circumstances back home and make it to the star-spangled promised land.

After Elena’s own unsuccessful attempt to go north, she became even more deeply embroiled with the MS-13 crew. One night, at one of the pop-up techno parties she frequented as a partier and dealer, someone she’d never seen before in her life sidled up to her enthusiastically.

“Lucia!” he said, throwing his arms around her. Her reputation, she realized, now preceded her. She was infamous, but also newly vulnerable—to the authorities, and to other gang members and rival dealers. The moment rattled her.

She was selling a lot and making a lot of money. Even her bosses at the call center were buying from her now. The gang guys loved her for it. “I’d go, I’d buy, I’d sell, I’d hang around with them, I’d do stuff for them.” And she was still managing to live the party life and make an honest living at the call center.

There was a low-level current of fear, of course—sometimes people came around her house looking for drugs, something she’d have to explain to her dad and brush off as nothing, a mistake.

And the higher-ups had started asking increasing favors of her—favors that weren’t exactly favors, in the sense that she knew she had no choice to say no. A girl boss who lived nearby—a really fierce-looking chick, Elena said—once asked her to go pick up a load in her car downtown, a big load, and bring it back to their smaller town. She couldn’t say no.

Meanwhile, Smiley got busted and went to prison. It was a sobering moment that punctured what little veneer of invincibility surrounded the operation. Nevertheless, he maintained contact by cell phone (phones were prohibited in prison, but easy enough to get hold of), and continued calling the local shots.

He’d check in on Elena once a week or so.

“How you doing? How’s work? How’s everything?” he would ask.

She was being watched, and reported on back to Smiley, as was common practice (the job of young gang underlings, or perritos—puppies—is to record the comings and goings and report back to the boss). One night she was out partying too late, and missed work at the call center. The next day, she decided again not to go. The day after that, he called.

“Why did you miss work?” he said. She fumbled for an excuse. Her job, they both knew, was her cover.

“Don’t be stupid,” he said. “If you want to get yourself into the women’s prison, fine, I’ll make sure someone beats the shit out of you when you get there.”

She went back to the call center the next day.

The thing is, she explains now, is that a gang is like a family—it filled some void for her. Of course it was even more attractive to those lacking a family or a caretaker entirely—particularly poor young men and boys. In a gang, you have somewhere to stay, someone to cook for you, to take care of you, to cover for you, to root for you. You have a place where you belong.

During this time, someone shot and killed Elena’s beloved family dog. She thought she knew who it was: a neighbor who had always hated the dog and yelled at him to shut up whenever he was barking. She was devastated, and word got back to Smiley in prison.

“I heard about your dog,” Smiley said the next time he called. “You know who did it?”

“I don’t know,” she said, choosing not to share her suspicions.

“You want me to take care of it?” he asked.

“No, that’s OK, don’t worry about it,” she said.

“Perro por perro,” he replied. “Dog for a dog.”

The Instituto de Medicina Legal is a complex of single-story buildings that meander through a large, guarded courtyard teeming with plants and flowers. On first glance, you might mistake it for some tropical bed-and-breakfast, but this lush compound in San Salvador is essentially the morgue. I watch through a glass-paneled door as a doctor inside the examination room cuts into a fresh corpse, whose flesh wiggles like a fatty breast of chicken. When the door swings open, the press officer shoos me out of the building—last time, she says, the ammonia fumes were so strong she’d gotten an eye infection. Back in the fresh air, she explains that, after the doctor determines the cause of death, they’ll slide the body back into the freezer and wait for someone to come identify the remains. If no one comes, which sometimes happens—it’s too overwhelming, or too far, or the family doesn’t have the money, or the deceased doesn’t have a family, or the circumstances of the murder are such that it’s best for the next of kin to lay low—the body is incinerated.

But any corpse in San Salvador that has gone undiscovered long enough, in a corn field, say, or cast into the dump, doesn’t have enough tissue left for an autopsy, so is taken instead to the Department of Forensic Anthropology.

In contrast to the blossoming courtyard, the forensic anthropology room is clean and antiseptic, all right angles and order. Meticulously assembled bones lie on gleaming metal examination tables. Diagrams of the human skeletal structure hang on the walls, and boxes are stacked against the counters and tables, all full of bones yet to be put back together.

Men and women are murdered every day in El Salvador. The vast majority of them are poor young men living in rural areas or urban slums. Yet the number of women who are murdered each year with impunity is among the highest in the world.

“This one here came from a mass grave in San Salvador,” Munisha Kailley, a forensic archaeologist at the lab, explained. The team had uncovered the cementerio clandestino a few months back, in a pit behind a San Salvador slum. She’d been a young woman—they estimated about 17 years old—who was killed within the last 12 months. Based on the subtle markings on the inside of her pelvis, she’d once given birth vaginally. In the front of her skull, just above where the young woman might have tweezed her brows or dusted on a shimmer of shadow, was a splintered hole. “A heavy object,” the anthropologist said.

They’d cut a neat rectangle out of the young mother’s femur, for DNA. Last year, Kailley estimated, they’d found a match for over half of the bodies—something she was proud of. But even if they figure out who this young skeleton once was, it’s almost certain that they’ll never find out for sure who killed her, or why.

ORMUSA conducted an investigation of women reported murdered by the national press in 2015. According to their count, the Salvadoran press—which consisted of at least 10 papers, print and digital—reported on 304 femicides, about 53 percent of the country’s total. Of those thought to be the result of gang violence, the majority of the victims were young women under the age of 25, and either authorities or the press linked the victims to gang activity. “This thesis tends to reinforce that the women themselves are responsible for their own victimization, or minimizes the cruel act of these crimes,” the ORMUSA report reads.

“Politicians say it’s only gangsters being killed,” Dr. José Miguel Fortín Magaña told me. “Which is patently not true.”

A distinguished-looking gentleman in his early 50s, Magaña was director of the Instituto de Medicina Legal. His office looked like an eccentric movie set, featuring tile floors, classical music theatrically keening through the speakers, and an immaculate, dust-free desk stacked neatly with papers, a snakeskin letter opener, and a magnifying glass. “Look at this,” he ordered, pointing at his computer screen and fiddling with the mouse. A photograph appeared of two young women dressed in blue medical scrubs, smiling against a backdrop of lush green.

“These two girls were about to graduate from nursing school. This was taken the day before they were killed.” He then showed me another picture—a rotting hand, skin pallid and wet and malformed, as if curdled, swollen against a thin silver ring. He switched back to the original picture. “See that? Same ring, same hand.” He then showed an image of bits of muddy, bundled blue cloth—the medical scrubs—found beside her naked body. Both bodies had been successfully identified a few days after they’d been killed.

“Do these look like gangsters? No! These were young women, innocent young people who would have been absolutely valuable to this society. And they killed them.”

Earlier that day, as I’d waited for my meeting with Magaña, there had been a woman crying quietly at the front gate of the morgue, shoulders quaking as she pressed a tissue beneath her eye. She leaned into a young man, her son perhaps, who wore a stiff expression and aviator sunglasses that reflected the day’s searing rays. The armed guards noticed the commotion, then looked away.

A different woman entered the gate. “I’m here to register a disappeared?” she said quietly, like a question. The guard pointed where to go with one hand, holding his gun with the other.

If your local police haven’t found the person you’re looking for, you go to the morgue to register the disappeared. The Instituto de Medicina Legal fixes the photographs to a bulletin board inside a plastic case so clean it reflects a glazed shadow of the onlooker, a flickering superimposition against the black-and-white photos of men and women, adults and children, arranged by date last seen. It was late July, and April’s disappeared had just been taken down.

“Thank you for your attention,” read the sign.

“Those guys were either going to kill me or get me sent to jail,” Elena now understands. Whatever semblance of friendship there was, she knew, was secondary to the business of MS-13. Looking back, the final straw for her was when Smiley asked her to take a trip to Guatemala.

“You have your license, right?” he asked. He knew she did. And she knew it wasn’t really a question—he needed her to drive somewhere.

“Don’t worry,” he said. All she’d have to do is take a car that would be provided for her, drive it to the border of Guatemala, and then turn around and drive it back. Easy. One of the perritos would be assigned to go with her. She wouldn’t ever have to get out of the driver’s seat: She’d just pull over at the designated spot, wait for the perrito to get out and load the trunk, and then drive on home.

Elena was so drug-addled at this point that she alternated between extreme paranoia and the friendly oblivion of denial. But this trip shook her up bad. When the car showed up, it had diplomatic plates. She drove, trembling, all the way to the border and back. Then she started dreaming up ways to vanish.

A few weeks later, still shaken and not quite sure how to extract herself, she headed to the destroyer house to pick up some more merchandise.

A friend drove her to the smattering of houses. She’d planned to walk in, grab what she needed, and walk back out. But when they got there, the narrow pathway to the destroyer was plugged with police and crisscrossed with caution tape. They had arrested a few of the perritos she knew, and seven corpses were laid out on the ground. “They’d been pulled from a grave behind the destroyer house,” she recalled. A grave she had never known was there. She glanced toward the police and the bodies, and then looked away.

Within a week, she had fled to a neighboring country.

Elena is sober now and has settled into a career, but every time she goes back to El Salvador—for work, or to visit family—she worries that she’ll be found out.

She remains haunted by the memory of those bodies laid out in front of the destroyer house. She’ll never know for sure, but as she looked out at the scene, she felt certain that one of the bodies excavated from the cementerio clandestino was that girlfriend of Smiley’s, the one who had supposedly gone to the North, her half-rotted body now splayed on the ground and surrounded by caution tape.

Elena had never been a typical gang recruit, or a typical gang member—her social class, her relationship to the boss, and even her sexuality reserved for her a rare position as an insider-outsider. But she could have just as easily become a typical victim.

When she saw those dead bodies in the dirt that day, Elena had kept her cool. As soon as the car rolled past the police and the caution tape, she told her friend to drive, just drive, to keep on driving. Then, one of the lucky ones, she engineered a way to disappear herself from El Salvador altogether.

*Some of the names and dates in this story have been changed.

A version of this story, which was reported with the help of an Immigration Journalism Fellowship from the French-American Foundation, originally appeared in the October 2017 issue of Pacific Standard.