Celebrity fossils are nothing new. From Lucy to Sue the T-Rex, there is a long tradition of taking an important fossil discovery and anthropomorphizing it, thereby imbuing the fossil with personality and cultural cachet. But could a famous fossil be more than just a celebrity? Could it serve as a tool of global diplomacy?

At the turn of the 20th century, the American industrialist Andrew Carnegie certainly thought so. And he had just the dinosaur, the capital, and the ego to put that theory to the test.

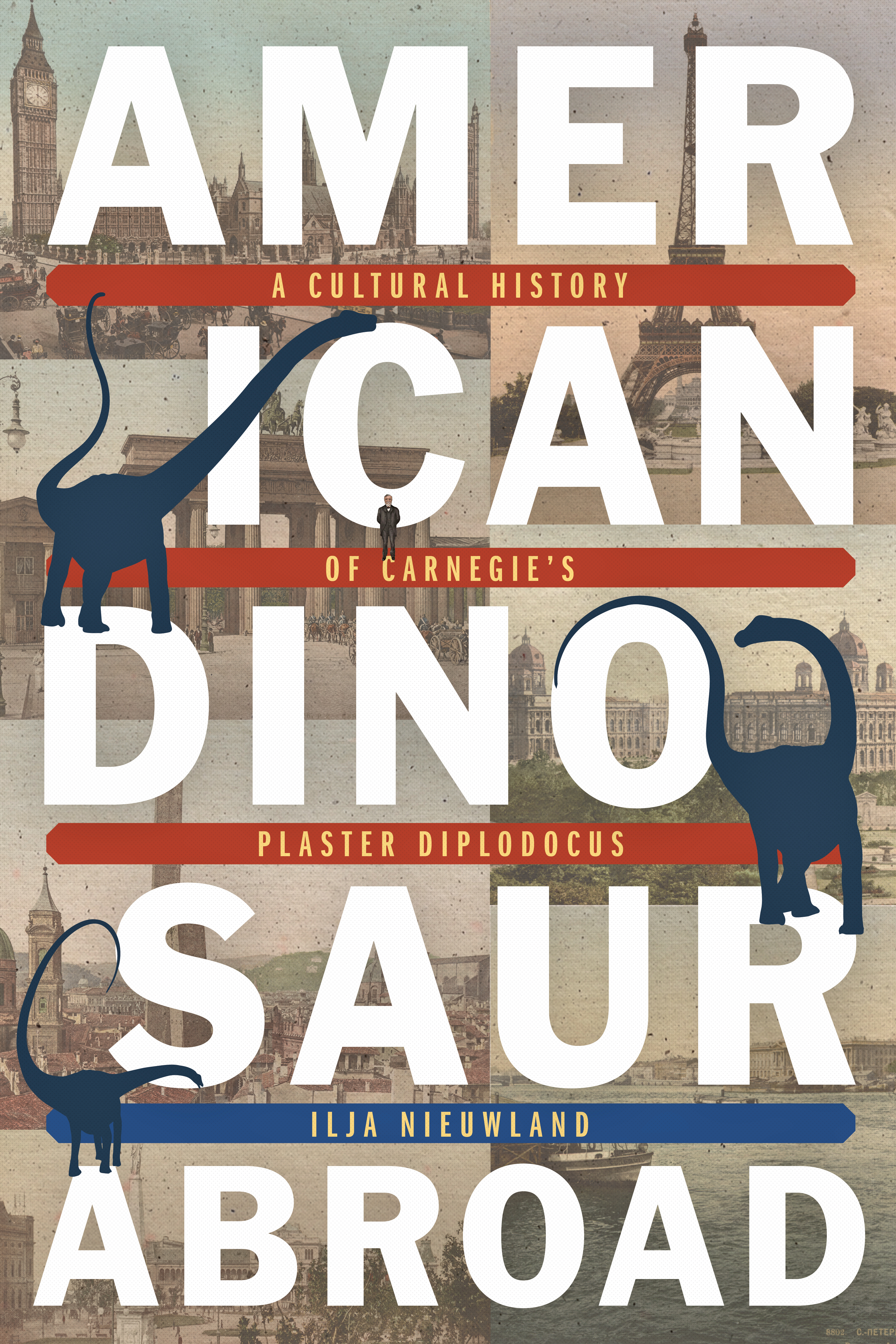

With the discovery of Diplodocus carnegii from Wyoming—a new Diplodocus species named for Carnegie, who had financed the expedition that unearthed it—the industrialist commissioned casts of his new fossil species and magnanimously distributed them throughout natural history museums in Europe. In American Dinosaur Abroad: A Cultural History of Carnegie’s Plaster Diplodocus, Ilja Nieuwland offers a biography of these casts, tracing the rise of their celebrity in scientific and cultural circles and showing that the “fossils,” vis-à-vis their casts, still matter today. The book is a story of science and history, but it’s also a close reading of how fossils and their replicas become tools of capitalism, power, and privilege. And it’s a story that Nieuwland tells particularly well.

Often compared to a 90-foot suspension bridge, Diplodocus was a gargantuan Upper Jurassic plant-eater with an extremely long neck and a whip-like tail. It’s an easily recognizable sauropod, even to contemporary non-experts. In 1899, however, Diplodocus was not a particularly interesting dinosaur, as several different Diplodocus species had already been discovered. But when the director of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History William J. Holland led a Carnegie-financed expedition to Sheep’s Creek, Wyoming, and unearthed a new Diplodocus species, the nearly complete skeleton piqued the curiosity of scientists while catching the public imagination.

This new Diplodocus was of deeper interest to the scientific community than previously discovered Diplodocus species, as paleontologists could now study new aspects of Diplodocus behavior, thanks to the well-preserved fossil skeleton. Even before the sauropod was completely excavated, tourists flocked to “Camp Carnegie” in Wyoming for a peek at the latest, greatest dinosaur discovery, thus making that Diplodocus an instant celebrity. The bones were shipped back to Pittsburg in 130 crates.

(Photo: University of Pittsburgh Press)

Although it was famous in the United States from the moment it was discovered, Diplodocus carnegii rose to international prominence only when Carnegie had plaster casts of it made, shipped, and assembled across Europe. Creating and disseminating casts of this size was a massive engineering undertaking in itself, and museums in Europe wouldn’t have been able to afford the specimens without Carnegie’s help. And the industrialist was willing to pay: Not only would these installations showcase American paleontology and stand as a grandiose gesture of philanthropy, Carnegie argued; they could also, he said, perform what Nieuwland calls”dinosaur diplomacy” during a period of increasingly hostile European tensions.

It is important, Nieuwland points out, to remember that dinosaur expeditions were a huge investment of time and capital—just the sort of thing, in other words, that appealed to Carnegie’s investments in American science and culture at the turn of the 20th century. Making plaster casts of the fossils required immense amounts of material and workspace, as well as serious investment of effort and money to ship the casts around the world. Ultimately, Carnegie had 10 copies of the Diplodocus carnegeii made and sent to museums in London, Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Moscow, and Buenos Aires. The replicas begat an international sensation: “Diplodocus became, without question, the most-watched dinosaur in the world and a household name, at least for a while, in many European countries,” Nieuwand writes. “It exerted an influence on European culture that went far beyond that of other dinosaurs.”

Take Dippy, for example. Dippy is one of the original Diplodocus casts that Carnegie commissioned and shipped to London. It was 70 feet long and arrived in 36 crates in 1904. When Dippy was put on prominent display in London’s Natural History Museum in the early 1900s, it wasn’t just a dinosaur that museum-goers were looking at; they were also seeing an American gift to the museum. Further, they were getting a glimpse of Carnegie’s control over who got to create and disseminate science in this way. (When the Natural History Museum in London removed Dippy in 2017 to make room for a blue whale skeleton, the move prompted ceremony, fanfare, and even a documentary narrated by Sir David Attenborough.)

Once Carnegie had promised a Diplodocus cast to London, news of the gift spread throughout Europe’s network of museums. Carnegie’s next idea was to offer the casts to European heads of state for their national museums as a way to foster collaboration in an ever-globalizing scientific community, as well as to promote peaceful political dialogue between countries.

(Photo: Courtesy of Ilja Nieuwland)

But was dispensing copies of Diplodocus carnegii truly diplomatic? And what did it ultimately accomplish? Nieuwland certainly presents a convincing case that Andrew Carnegie thought what he was doing was diplomacy. Thanks to his social and business connections, Carnegie saw himself as uniquely positioned to defuse political tensions in Europe by giving European leaders dinosaur casts that evoked a deep, shared earthly history. More than anything, in American Dinosaur Abroad, Carnegie comes across as egotistical, narcissistic, and naïve to imagine that a Diplodocus—as charming and immense as the sauropod might be—could solve the problems that led to World War I.

More than just a story of failed diplomacy, however, American Dinosaur Abroad reads as the successful tale of how an American industrialist came to control a piece of American natural history. The scale of the early 20th-century dinosaur digs required heavy financial support from a source like Carnegie. But with that investment also came control of the fossils: The Carnegie Museum got to decide who would enjoy access to the actual dinosaur bones for study. And since the museum made the casts, the museum could choose who to bequeath them to, while also sending some at Carnegie’s personal direction. (There were museums that wanted a Diplodocus whose requests Holland declined.) Nieuwland leaves us with the idea that Carnegie thus “produced” Diplodocus in the same way that Carnegie produced steel, and it is impossible to separate the dinosaur from the capital that made its reproduction possible.

Nieuwland’s book bespeaks his careful examination of newspapers and the historical ephemera that recount the making and shipping of these Diplodocus casts. Although it takes a bit of time for the stories to pick up (the first chapter of the book is heavy on method and theory), the anecdotes and characters are well worth the wait. There are, for example, a plethora of museum curators endlessly arguing with each other about how to appropriately articulate the dinosaur’s bones: What pose should the Diplodocus strike? What if the museum doesn’t have the physical space to stretch out a 90-foot dinosaur?!? It’d be inaccurate to coil the tail, but what else can we do in such a small space? As Nieuwland tells these stories, it begins to sound like figuring out how to stage the Dilodocus casts in various museums was often like trying to figure out how to arrange the world’s most awkward furniture.

American Dinosaur Abroad offers a well-researched example of how paleontological patronage ensured the scientific, social, and commercial success of a dinosaur. It’s also a fascinating window into the idiosyncratic hubris of one of America’s most consequential barons.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.