A few months after the 2015 shooting at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, once the hordes of national reporters covering its aftermath had thinned, Charleston-based Post and Courier reporter Jennifer Berry Hawes decided there was more to be written on the attack. While she was reporting her first story about the shooting, Hawes and a photographer went to take a picture of two survivors in the church sanctuary on a weekday; they had often taken photos there for religion stories. This time, though, they saw an Emanuel AME administrator blocking the survivors from entering, prompting one survivor, Felicia Sanders, to burst into tears and say that she was losing her church.

“It was a moment where I realized there was a lot more going on in this story than [had] met the eye so far,” recalls Hawes, who later uncovered how Sanders had clashed with the church administration after the shooting. When a literary agent called from New York asking if she would be interested in writing a book expanding on her reporting, Hawes began documenting the lives of Sanders, fellow shooting survivor Polly Sheppard, the families of the shooting’s nine victims, then-Governor Nikki Haley, and perpetrator Dylann Roof, among others, long after the shooting’s nine victims had been buried.

The book resulting from that reporting, Grace Will Lead Us Home: The Charleston Church Massacre and the Hard, Inspiring Road to Forgiveness, bears an uplifting title but offers a painful glimpse into the ways a community does, and doesn’t, recover from a mass shooting. Hawes documents how, after the attack, Emanuel AME continued to find itself at the heart of local dramas: The church was sued by a victim’s husband over its handling of donations, many of which were earmarked for survivors and victim family members but never reached them. One survivor, deeply disappointed in the church leadership’s response to the shooting, left the congregation. Two daughters of one victim erected competing tombstones for their mother. By threading these conflicts through the book, Hawes aimed to create a richer portrait than one finds in typical media coverage of mass shootings, which too often “categorizes” survivors and grieving family members into hackneyed archetypes, she says.

Hawes spoke with Pacific Standard about how mass shootings affect small cities like Charleston and Parkland, Florida; the thornier conventions of mass-shooting press coverage that she’s sought to avoid; and why she wasn’t interested in making Dylann Roof a major character. All profits that the Post and Courier sees from the book, Hawes says, will go toward creating paid internships for aspiring journalists of color.

How did you initially win the trust of the shooting survivors at a time when they were probably being overwhelmed by contact from the media?

When I was initially trying to get to them after the shooting, I didn’t have any luck. I decided to wait and be patient because if you just give it some time and let people cope for a little while, then they’re much more likely to talk to you, and in a more thoughtful way. So that’s what I did here: A few months after [the shooting], [the survivors’] attorney, Andy Savage, wrote a post about how people remember the dead but aren’t attuned to what’s going on with the living, and so I reached out to Andy. I didn’t know him really at all, but I’ve been here in Charleston reporting for upward of 20 years, and I’ve reached out to him for a number of stories. Basically, Andy went to [the survivors] on my behalf. In this case, that helped me, versus some of the national reporters who just didn’t have that relationship with people in town.

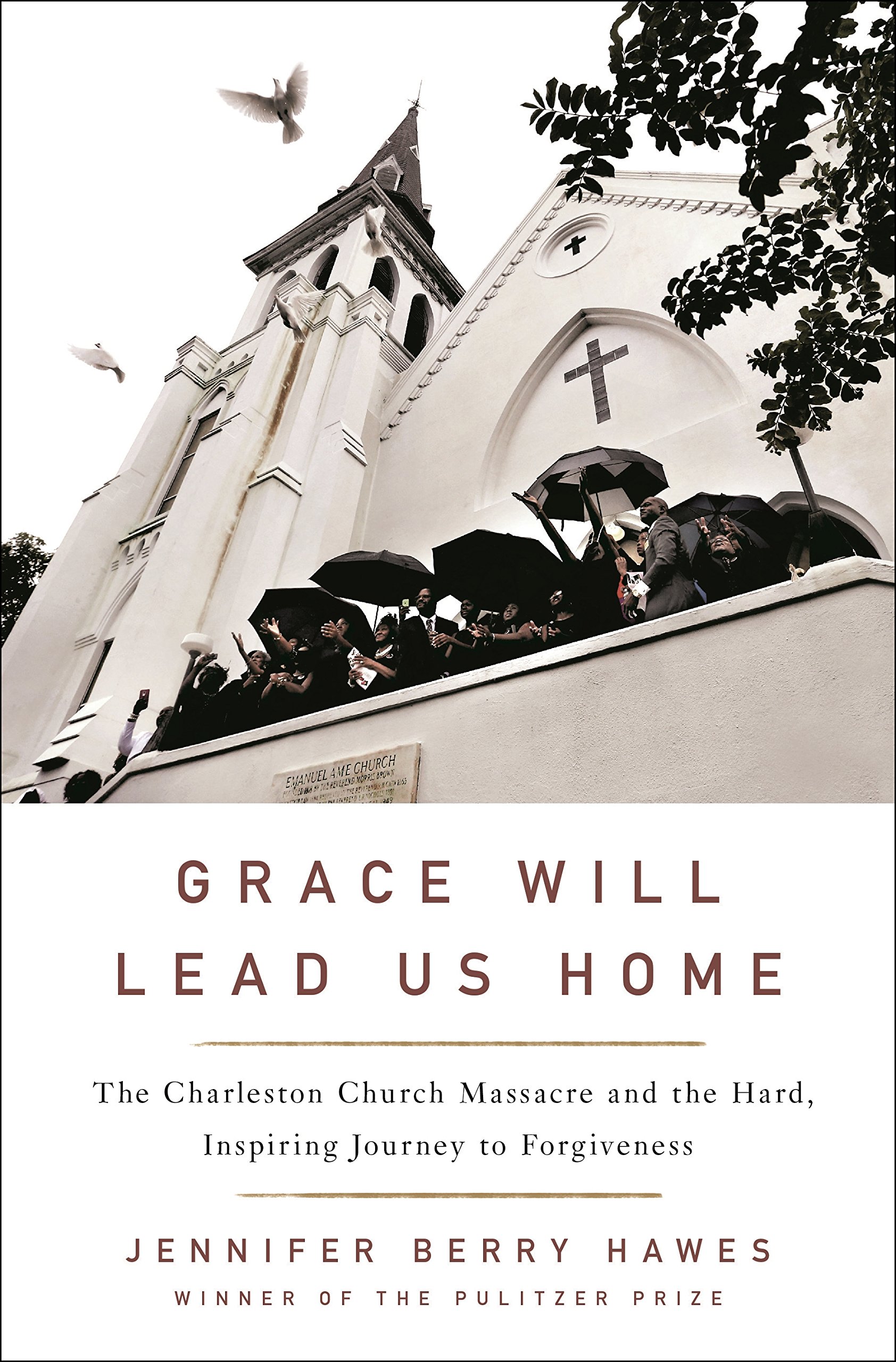

(Photo: St. Martin’s Press)

Part of the book retraces the day of the shooting. How did you approach getting survivors to walk you through the details of that day?

By that time, they were pretty ready to talk. They had decided to meet with me, they knew why I wanted to meet them, and I don’t recall asking a lot of questions. I was impressed that they were able to let it out in such detail, given really only a few months had passed. Between the court records and my conversations with them, I felt like we had a pretty good idea of what happened, and I didn’t have to keep going over it with them and ask them to keep reliving it.

You note in your introduction that you had a particular lens on this story as a white reporter. How did you seek to bridge the divide between the experience of your primarily black subjects and your own perspective in your reporting?

I tried really hard—and I think this is true of any story where you’re writing about people whose experiences are different from your own—to write and ask questions that allowed me to tell the story through their eyes. Generally I tried to stick as much as possible to telling the story strictly through their eyes and their thoughts and their feelings and what they saw—what they were telling me they experienced. Often, my editor of the book would say, “Try and analyze the situation more,” and sometimes I would resist, because I didn’t want to do that; I didn’t want to write a book from my perspective. Now, I’m sure there are parts where my experiences bleed in that I [didn’t] intend to. But I tried very hard to remain a storyteller and not an analyst.

There’s always a debate about how much attention reporters should give to perpetrators of mass shootings. You spend some time talking about Dylann Roof’s life—how did you decide how much space to give him in the book?

From the get-go, when I talked with publishers, I was adamant I did not want to write a book about Dylann Roof. The way I tried to use him was for context: You cannot understand the shooting without understanding his racist views, or without understanding white supremacy in America and how it’s enjoying a heyday on these websites. So I referenced him inasmuch as I felt it was important to provide the context of racism today, and his racist views, and how he came to hold them.

In this case, because he was driven by a specific ideology that continues to exist in America, we have to understand that ideology, and it continues to exist and flourish. You can look at the Tree of Life shooting in Pittsburgh; it’s not as if it was a one-and-done deal. This was someone driven by propaganda, essentially, that is still widely available. And to understand it, and therefore hopefully do something about it, we have to name [the shooter], and we have to understand how he came to hold those views.

Did you seek any access to Roof and his relatives?

I wrote to his immediate family members, more than once, as I recall. I reached out to their attorney [and] I did write to Roof when he was still in the jail here, but I never heard back from any of them, and they never sat down with a reporter to discuss in any length what happened. And then, because Roof represented himself during the penalty phase of the trial, which he did specifically to keep that information [from his family] out, we never heard from them. So they’re a great black hole. I didn’t pursue [Roof] really strongly because he was a very flat character. His views remained steady; he even wrote after the shooting, “I have not shed a tear for any of the innocent people I killed”—it wasn’t as if he went through a metamorphosis that would make for an interesting story.

Were there any particular tics in how newspapers and magazines write about mass shootings that you worked to avoid in this book?

This is one of the main things I wanted to get across: that if you look at news coverage of mass shootings, you see our temptation to categorize people into these lumps. You have the activist kids from Parkland, the saintly black Christians in Charleston. We pigeonhole them into these groups as if they’re homogenous people, and in fact they’re not, and Emanuel is no different. These are all very different people who had diverse thoughts and opinions—I mean, look at the forgiveness narrative, that’s a key one. Everyone points to the notion that all of the families of the survivors forgave Dylann Roof two days after the shooting, at his bond hearing, and that is just not true. There were five family members who spoke at his bond hearing; three of them referenced forgiveness. They all spoke in Christian themes of love and mercy and forgiveness and grace, but they were [just] one group.

If you talk to all of the survivors and a whole variety of family members, you’ll see some family members didn’t forgive him. And the people who died are all human beings who are different. They may share one thing in common, they may all be Christians, or in this case, they may all be black, but they are not all the same person. As journalists, we do them a disservice by painting them that way when in fact the story’s a whole lot more interesting.

(Photo: Grace Beahm Alford)

Since the Emanuel AME shooting, we’ve seen shootings in Las Vegas, Orlando, and Parkland, among others. Did writing this book change the way you process news of mass shootings in any way?

I was talking at an event for this book to launch it, and I explained that I had come to think of these shootings as a rock being thrown into a pond—you see the initial splash where the rock hits the water, and then these rings form and form and form and spread across the surface of the water. That’s how it affects a community: In a city the size of Charleston or Aurora or Parkland, that affects everybody. It affects so many people, so that now, whenever I hear about [mass shootings], I’m instantly struck that not only are people who lost loved ones just finding out, but I remember the surreal nature of our city for weeks on end, and then know that it’s going to have an enormous impact on that city for years to come. It really makes me feel very sad as a human being that we’re not doing more to prevent this from happening.

The subtitle of the book calls the journey of these survivors “inspiring.” What about this story do you hope will inspire readers?

Well, the fact that they survived with any degree of normalcy. I can’t imagine what it’s like to be in the room essentially the size of a classroom and have 77 bullets shot into the people around you. How do you even go forward day by day? And you’ve got to keep in mind, it’s not just the loss from the shooting, but all of a sudden, everybody wants something to do with [the survivors]. Everybody wants a part of them. Everybody wants to make some money off of them. Everything about their lives changed, and to see them now, four years later, really finding their feet—and for many of them, their missions—to me that’s inspiring. Because I wasn’t sure along the way how it would turn out for some of them.

Do you keep in contact with any of the survivors now that you’ve finished the book?

I still see some of them because I cover things like anniversary events [at AME], but not as much as I did, and honestly that’s a bit of a relief. Because really, for about two and a half years, I was constantly pressing, trying to get access and spend time with them. As a reporter, that was the hardest part, that constant pressing. Because you want to be gentle and sensitive, but you also want to tell their story. I knew they would be glad that they had in the end because I’ve seen that many, many times with stories about sensitive things: Once it runs and they’re happy with it, they’re glad they did it. But it doesn’t always feel like that. It is a relief just to see them and ask “Hey, how are you?” and that’s really all I want to know.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.