(Photo: Courtesy of Perry Dino)

The painter Perry Dino always dresses the same way for a protest: a black half-sleeved T-shirt, blue jeans or slacks, and sneakers. He jokes that it’s his uniform, “like Batman”—an outfit that won’t get stained by dirt, sweat, or pepper spray and that offers protection from all sorts of weather. For a recent protest in his native Hong Kong against a proposed law that would allow citizens to be extradited to mainland China for trial, he added a hat to protect himself from the sun. He also brought along the rolling suitcase he’s learned to pack just-so to fit his easel, brushes, and palette.

For particularly large protests, he works at the starting point, and the organizers of the April 28th march had called for a huge street presence. So Dino made for the city’s Causeway Bay neighborhood, arriving there an hour before the event started. Then he set up his easel and began to paint.

He spent four hours working at the scene and taking photos to use for reference later in his studio. During a break, he met up briefly with his friend, Kacey Wong, another protest artist. Wong had created a special participatory artwork for the occasion, a mobile jail where protesters could strike poses of humor or defiance. Dino, too, had his photo taken in fake prison before returning to his painting.

It was a good day, all in all, he thought. Some people, recognizing him as the famous Hong Kong protest painter—the artist they had seen at so many marches, rallies, and vigils—clapped him on the back between brushstrokes or yelled encouragement as he worked. No one asked to buy his painting, so he didn’t have to explain that he almost never sells his work, fearing it could end up on the mainland and be destroyed. He didn’t need to wear a gas mask, and the police didn’t taunt or threaten him.

“Protest painting, it’s always a little bit dangerous,” Dino says, acknowledging that the possibility of arrest is ever present. But to him the risk is worth it for what he’s able to create: a record, traced in oil paint, that shows the people of Hong Kong using their voices freely. Even after a 2016 bout of pancreatitis caused in part by exhaustion from doggedly recording protest after protest, Dino is determined not to abandon his work recording the city’s tumultuous present. As the rights of Hong Kong’s public slowly erode, he continues to don his “uniform” and wield his paints and canvas as witness to a city’s struggle for self-determination against overwhelming odds.

“He’s quite a sight,” Kacey Wong says of his friend’s protest rituals. “Everybody is angry and shouting; protests are like organized chaos. And then there’s this guy in this traditional painter look with the easel and apron. What he’s missing is the French beret.” He laughs. “But it would be too hot for Hong Kong.”

Wong describes Dino as hardworking, loyal, and tougher than he looks. Getting too political in the Hong Kong art scene is a “major no-no,” Wong says. “You can’t sell your work. If you’re in school, your professor will definitely recommend against [pursuing political art].” The path can be lonely, and it requires a threat tolerance that many artists don’t possess, especially artists who, like Dino, have two children. His wife, a civil servant, feels obligated to remain professionally neutral but is deeply proud of her husband’s work.

Dino acknowledges the inherent risks of that work even with the signatures on his paintings. Perry is his real first name, but his last name is a nom de plume—or nom de guerre. He proudly explains that Dino means “crazy guy” in Cantonese, but he wasn’t always so bold.

(Photo: Benson Tsang)

Hundreds, or by some accounts thousands, of protesters were killed during the Tiananmen Square protests on June 4th, 1989. Dino was an art student in Hong Kong at the time, and thinking about it makes his eyes fill even now. He spent the day watching television, growing progressively more horrified by the news out of Tiananmen and torn over what to do. Art school at the time was exceptionally competitive. He felt a deep push toward joining the city’s huge solidarity protests. But he was also acutely aware that getting too behind on assignments could lead him to flunk out. He chose his homework, but the choice haunted him.

After graduation, he worked in advertising before moving into art teaching. He also often enjoyed open-air painting, but the idea of painting a protest—or painting as protest—did not occur to him until 2012. When the haute couture house Dolce & Gabbana opened a new store in Hong Kong, it issued a controversial rule against photos, ostensibly to prevent the creation of knock-offs. But it seemed to many locals that the rule was being enforced unevenly by police in favor of mainland Chinese visitors, who were allowed to take pictures where and when they liked. Several friends invited Dino to take rebellious photos in front of the store to make a statement, but he did them one better, bringing paints and canvas. The policy, he pointed out, did not forbid painting.

The next day, Dino’s image was all over the news. The media loved his impish take on the issue, but he found the attention overwhelming. He resolved to hide out and not let his art get too political.

He remained successfully neutral and under the radar until several months later, when he found himself in an assembly commemorating Tiananmen at the school where he taught. (Hong Kong is the only Chinese city permitted to observe the Tiananmen anniversary. The city’s annual memorial vigil often draws tens of thousands of people.) The school’s headmaster showed one of the famous images of tanks in Tiananmen Square as they advanced on peacefully protesting students, and Dino found himself overwhelmed by years of guilt.

“Here I am, a teacher, with all my students standing in front of me,” he says. “And I’m in the back crying. On that day I decided to go [paint] again.”

In 2014, what became known as the Umbrella Movement shut down some of Hong Kong’s most significant roadways for 79 days. Hundreds of thousands of Hong Kongers took part in peaceful protests calling for the free elections they’d been promised when the United Kingdom returned the city to China in 1997. Dino was there painting feverishly, sometimes for 11 hours at a stretch, rinsing his brushes at a shopping mall near his studio when he finished for the night.

(Photo: Perry Dino)

The pieces he completed during that time provide insight into a fleeting world of political possibility. Some days, Dino painted the tidy realm of the “Occupy Central” area near Admiralty, where students held teach-ins among colorful tents, and the spotlessness of the volunteer-maintained bank of toilets was legendary. Other times, he recorded the clashes between police and protesters in Mong Kok, where twice he painted from atop a metro station entrance to keep out of the melee.

Then, as now, he spent hours on the background of his paintings, then chose passersby with meaningful signs or interesting clothing to reflect the larger feel or atmosphere of the day. The approach allows him to access the core of a place or scene, he says, instead of just capturing a random, snapshot moment as a camera might. The wildly changing nature of his subjects and locations means that, in the course of this process, he sometimes has to switch perspective mid-stream and fight against ever-changing light. But the time required to complete each painting is meant to be part of its message: “The audience knows you went to that place, you bore the risk,” he says, for as long as it took. He sees that risk as a form of honor.

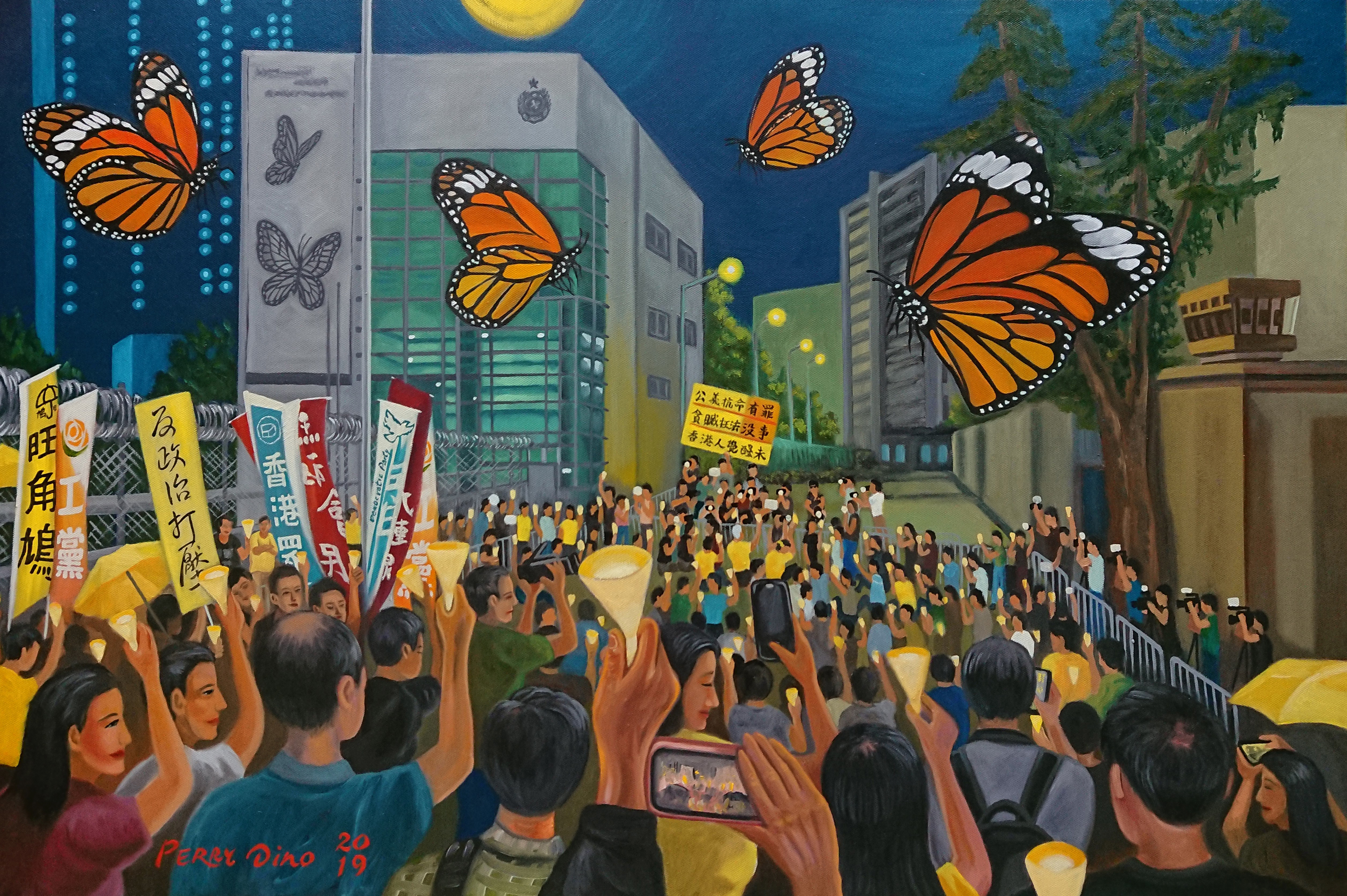

Recently, Dino has begun incorporating more fanciful elements into his painting. A piece from the trial of the so-called “Umbrella Nine”—protesters from the Umbrella Movement charged in April with public nuisance crimes that critics call archaic and vague—includes both bewigged barristers at argument and a sparrow in flight. A painting depicting a candlelight vigil protesting the subsequent imprisonment of four of those nine shows four butterflies fluttering free. This step toward abstraction is not just an artistic choice but a pragmatic one as well—a response to the increasingly threatening political clouds over Hong Kong.

(Photo: Perry Dino)

“There is a keen sense among people here in Hong Kong that their freedoms are deteriorating rapidly due to the encroachment of the Chinese government, and they are disappointed and worried about the future,” says Maya Wang, a senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch. She sees the imprisonment of the Umbrella Nine as just one example within a larger trend of the mainland “actively undermining” freedoms in Hong Kong, a city that has traditionally served as a haven for progressive ideas. In 2015, the detention of five employees of a bookstore specializing in political literature sent ripples of fear through the activist community. The mainland-backed city government has also ejected elected legislators who promoted Hong Kong autonomy and banished a foreign journalist who hosted a talk on the city’s independence movement.

Since the Umbrella Movement, Hong Kongers have been restive. But with a bill on the docket that would criminalize disrespect of the Chinese national anthem, and the proposed extradition law, tensions are again boiling over. Tens of thousands marched against the extradition bill at the April protest Dino attended.

Nominally, the extradition bill is meant to fill a loophole that prevents Hong Kong from extraditing criminals to certain countries, as well as the mainland. But that loophole was a human rights safeguard put in place during the negotiations for Hong Kong’s return to China, Wang says. Fear is spreading in the city that such a policy could be broadly applied, including in cases involving trumped up charges, making virtually anyone vulnerable. Although the new law could eventually result in widespread extraditions, Wang predicts that the immediate consequence will be intimidation, tamping down activism and free speech.The matter has become a political flashpoint in recent weeks. When it came up for debate at the legislative council, fistfights broke out among lawmakers.

(Photo: Perry Dino)

When he thinks of the future, Dino envisions a world where he could be arrested because one of his paintings offended authorities, then sent to prison on the mainland for life. What would happen to his family? Would the public ever see the retrospective exhibition he dreams of? Wang says he’s right to be afraid. Artists on the mainland regularly experience threats to their families. The political cartoonist Badiucao canceled an exhibition in Hong Kong following unspecified threats; another cartoonist living in Thailand was extradited to China by Thai authorities and sentenced to six years in prison.

The anthem bill is expected to be enacted later this year, and Wang predicts the extradition policy will be “rammed through” by July. But despite everything, Dino recently completed his largest art piece yet, to coincide with the 30th anniversary of Tiananmen.

The painting takes inspiration from Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, which famously depicts the Nazi destruction of a Basque town during the Spanish Civil War at the behest of Fascist leader Francisco Franco. Dino sees parallels between the Guernica massacre and what happened in Tiananmen—and with what’s happening now in Hong Kong. He recently obtained, at some risk, a USB stick containing more than 200 graphic photos from the Tiananmen protests. “Their bodies look like pizza,” he says of the dead protesters, his voice quavering. “The first time I saw the images, I cried.”

Dino and his artist friend, Wong, say they’ve mostly moved past the fear of whatever dangers their work might bring upon them. Some things are worth fighting for, no matter the cost. In this context, where simply to witness is to risk one’s life, Dino’s persistent act of creation has become one of deep defiance, creative inspiration, and cultural preservation.

“A painterly artist standing there not with a camera, [but] with an easel, what does that mean?” Wong says. “That means it’s historic, man. It’s the thing you see in the museums.”

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.