Perhaps it’s natural that unreliable narrators on film, television, and radio have been conspicuous since the 2016 election. Between The Woman in the Window, S-Town, and the third seasons of Mr. Robot and True Detective, millions of cultural consumers have voluntarily spent time since the election of President Donald Trump following characters who offer dubious accounts of themselves. The skill these titles require of readers, listeners, and viewers—simply put, to read critically—have been honed and strengthened by the daily act of scanning social media platforms and news outlets; distrusting the narrator, at this point, ought to be second nature for most of us.

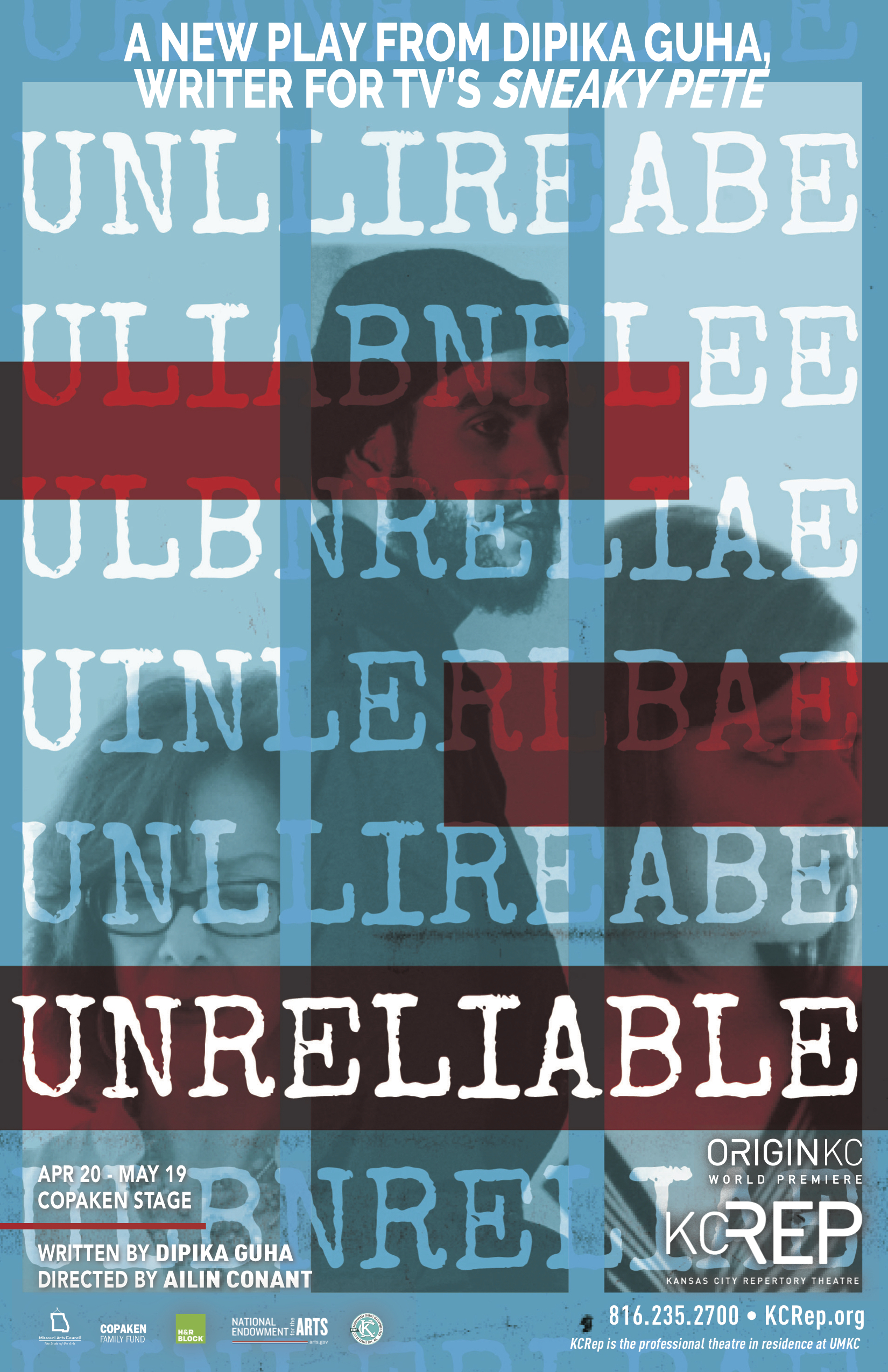

TV writer and playwright Dipika Guha finished her latest work, Unreliable, before the 2016 election. Yet the play, opening April 20th at the Kansas City Repertory Theater in Kansas City, Missouri, is well-suited to an era in which many pundits on TV and Twitter live by the factitious rules of their own realities. Unreliable features not one but three unreliable narrators: Yusuf, a man being held without trial on terrorism charges; his lawyer, Gretchen; and her adoptive mother, Hattie. All three meet at a remote prison that resembles Guantanamo Bay, each bullishly maintaining his or her own version of reality, no matter how deeply it conflicts with others’. Yusuf claims he has been framed, while others aren’t sure; Gretchen thinks she is a lawyer, but Hattie believes she is a secretary. Viewers are left to determine which aspects of the characters’ accounts are accurate, and to parse out “what our individual roles are on the fates of people who are far away, how our beliefs are tied to their fates, and how the everyday decisions that we make in America reverberate globally,” as Guha puts it.

Social and political criticism isn’t new for Guha, who often adds an element of comic absurdity to the big questions she poses in her works. In her 2018 play In Branau, a progressive American couple opens a “bed-and-dinner” in Adolf Hitler’s first Austrian home to expunge the space’s dark past. 2012’s Passing imagined an art exhibit that tells the story of an unhappy British married couple who move to an “exotic” fictional island in the 20th century and unofficially adopt an indigenous orphan after she has been brutally attacked.

But Unreliable is the “most explicitly political” of her plays, the Indian-born author says, in that it invites comparisons to the shameful conditions at Guantanamo. Still, while it was inspired by the prison’s “gross human-rights violations,” the play ultimately tells the story of a mother and daughter: “I’m looking for ways in which what’s happening on a macro scale is also happening in a small way in our everyday lives,” Guha says.

Before the premiere of Unreliable, the playwright and TV writer—who has also written for Amazon’s Sneaky Pete, and has another show currently in development for ABC—spoke with Pacific Standard to discuss how citizens and consumers in the Trump era need to develop better media literacy; how Showtime’s Homeland helped spread Islamophobia; and how writing for television has changed Guha’s writing for the stage.*

You’ve said previously that Unreliable is “perhaps the most explicitly political of my plays.” Besides Guantanamo, were there other political events running through your mind as you were writing it?

It’s really interesting: The play pre-dated fake news and the political implications that came from that in the last election. All of that was yet to come when I began writing the play. I was interested in the real-life consequences of the beliefs that we hold—what they are on people we can’t see. And then it all kind of blew up, and now the play feels timely in a strange way.

(Photo: Courtesy of Dipika Guha)

Has writing this play changed the way that you address politics in your work?

It definitely was me trying a different approach to questions that I’ve always been interested in. I think my plays have been small-P political, always, and I’m much more interested in the ways that history and politics play out in our everyday lives as normal people: what it feels like to feel political pressure in historical moments, what that feels like for people who aren’t big players in history.

This play felt very directly political for me because it deals with America and its role in international politics. That that was something I hadn’t really tackled before that. But it felt a lot more political a few years ago than it does now; now it just feels like, “Oh well, this is just clearly what’s happening.” Plays often take a really long time to get staged. Sometimes the play misses the moment by the time it gets staged, and sometimes it’s like the world catches up to the play. It’s a really strange thing.

Were you inspired by any particular works when you wrote this play, in content or approach?

I was thinking about, in particular, the TV show Homeland that was so brilliantly written but had a really Islamophobic plotline, kind of horrifyingly so, and it was leading up to the 2016 election and made me incredibly nervous in a way that sometimes things in popular culture can do. It felt like a premonition to me, that it was molding the way that we were thinking about Muslims, and then the election happened.

I was responding to not just what that show was saying about Muslims, but to how it was saying it, and how we were being asked to think about “the Other” in that context. And then there was a whole plethora of [other shows]; any time there was a Muslim on television, you were sure to be a terrorist, so I was responding to that.

Your new play includes characters with conflicting stories and no single, clear, “true” story. In this era of “fake news,” have audiences gotten more interested in unreliable narrators?

I think we are much more aware of it, and of course with fake news, we’re aware of it daily now. I don’t know how much more conscious that has made us in terms of our own fallibility or our own blind spots. Of course, they’re blind for a reason. I don’t know whether we’ve become better at knowing when we’re holding onto stories for our own benefit; that seems like it’s a very human trait that we all have. The stories that we tell ourselves about each other, and the stories that we tell ourselves about ourselves—there’s a gap in between these stories. Certainly, it’s as difficult as ever for us to talk to people with opposite views. It feels like it’s never been harder, in some ways. I don’t know, it feels like it’s gotten very thorny, all of it.

(Photo: Kansas City Repertory Theatre)

You’re currently working on an ABC series. Are you allowed to say what the series is?

I am. It’s a show that’s in development at ABC called Rainy Day People, and the showrunners are Christopher Cantwell and Chris Rogers, who wrote Halt and Catch Fire. This show is about a wellness center and a family-run business that welcomes people who want to heal themselves from various traumas, of varying degrees of seriousness. It’s kind of looking at addiction; in particular, the ways in which we’re addicted to all kinds of things, technology included, but it’s also tackling larger spiritual questions of what makes us happy—and why, when we have everything, we’re not happy—through the lens of this family.

Has writing for television changed your approach to writing for the stage?

It has. A literary manager once said to me, “I always know when playwrights have started writing for television; it’s different for each of you.” I don’t know what it does for other playwrights, but, for me, my attention to structure is much greater than it was before. I’ve always been interested and driven by form and I haven’t repeated a form in any of my plays, but television has a very particular way of setting things up and paying them off, structurally, and I had never done that with my plays before. So it’s been particularly useful for my writing, when you’re trying to strengthen what you already have. The generative process of my plays has stayed the same: The process of being in a writers’ room is mostly talking through ideas and testing them [together] over and over and over again and then mapping out a structure together, so there’s no writing that happens for a very long time.

With playwriting it’s the opposite. I feel like it’s always that the writing shows up first, and you find the play through writing it. With television, it feels like everything rests on sound structure, so my interest in it has grown, and I’m becoming much more attentive to the way the form in my plays holds up.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.

*Update—April 10th, 2019: This post has been updated to reflect that Rainy Day People is in development at ABC, not AMC.