How can we determine who’s winning the Democratic presidential nomination for 2020? Based on prior nomination cycles, there are quite a few indicators we can use. Polling is an obviously popular one, although is not always very predictive this far out. Endorsements can be useful. The preferences of party activists can be revealing. Fundraising is obviously important. Google searches might tell us something. But an under-reported indicator is staffing patterns.

Why might the staffing of presidential campaigns be important? Because campaign staff with a deep understanding of national politics and the skill set to run a presidential campaign are a scarce resource. Running a presidential campaign is complex: It requires making complicated decisions about fundraising and expenditure allocation, creating a communications program that’s attuned to local customs and concerns, knowing how to manage an ambitious candidate and his or her family, understanding at least 50 sets of rules for primary and caucus participation along with ballot filing deadlines and qualifications, and more. Not that many people know how to do it, and even fewer are good at it.

With roughly two dozen Democratic presidential candidates in the field right now, they won’t all get access to the same good campaign staff. Indeed, consultants, campaign managers, and others can act as a kind of gatekeeper to high office; with rare exceptions, candidates that don’t get to hire these people don’t get very far.

As gatekeepers, elite campaign staffers play an important role in a political party, as Jonathan Bernstein has written about for Bloomberg. They help with the party’s winnowing of candidates and determining who gets to be the nominee. When a party is able to coordinate elite endorsements, donations, and competent staff on the same candidate, it can effectively pick the nominee long before primary voters and caucus-goers ever weigh in.

Which brings us to the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination. Former Vice President Joe Biden has had a consistent, if modest, lead in polls for the past few months, and a similar lead in endorsements. (I say modest because we might expect a recent vice president for a popular administration to be doing better by these measures.) Senator Bernie Sanders has raised the most money. Activists in early primary states, like Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina, have been leaning toward Senators Kamala Harris and Cory Booker of late, according to FiveThirtyEight. There’s no overwhelmingly clear party signal here, although the same handful of candidates tends to dominate in all these measures.

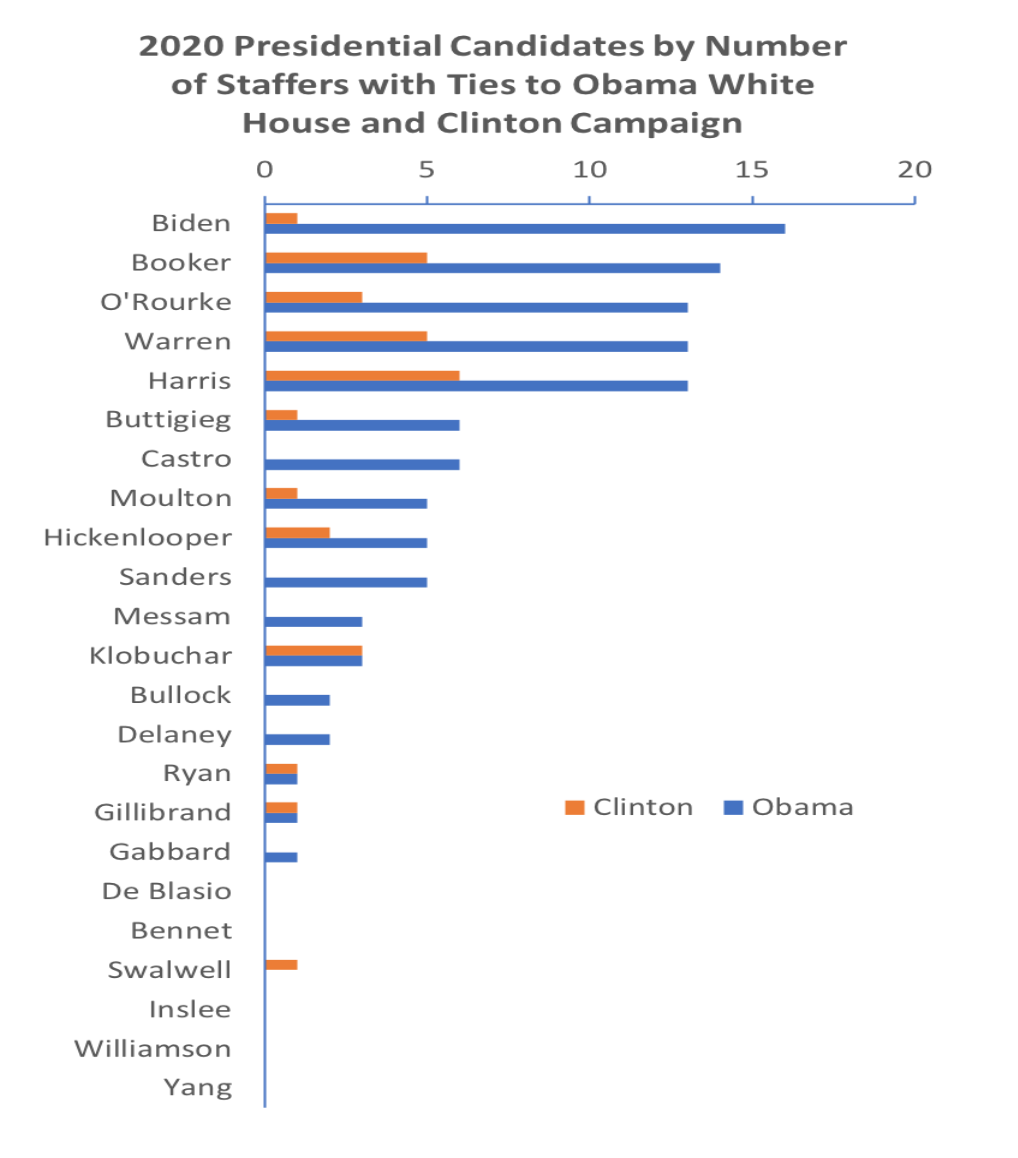

But what about campaign staff? To examine this, I drew on political scientist Eric Appleman’s Democracy in Action data collection. Appleman has put together lists of top staff for all the presidential candidates and provided brief résumés for each. Using this information, I could see how many staffers each candidate has employed who worked in the Barack Obama White House (but not necessarily on his campaigns), as well as how many worked for the Democratic Party’s most recent presidential nominee, Hillary Clinton. I don’t presume that this data set is exhaustive or up-to-date as of this very minute, but it should provide enough information to give us an idea of where this aspect of the party is leaning. (Thanks to David Bernstein and Josh Putnam for pointing me to this valuable resource.)

The chart below shows each Democratic presidential candidate ranked by the number of staffers they have who worked in the Obama White House (blue lines). I also indicate the number of staffers each candidate has who worked for the Hillary Clinton campaign (orange lines). Judging by Obama staff, Biden is in the lead, although not by very much; he essentially has the same number of Obama staffers in his employment as do Booker, Harris, Representative Beto O’Rourke, and Senator Elizabeth Warren. These candidates also have the highest numbers of former Clinton staffers, with the exception of Biden, who has only one (Deputy Communications Director for Strategic Planning Meghan Hays).

For the most part, this is, again, the same set of candidates who shows up at the top of other measures of support, although the presence of O’Rourke on this elite list is somewhat surprising. A second tier of candidates—South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg; former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Julián Castro; Representative Seth Moulton; former Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper; and Sanders—each have five or six Obama administration staffers. (Sanders unsurprisingly has none from the Clinton campaign.)

I also looked at the number of staffers from Sanders’ 2016 campaign who show up in the data set. There are 19 of them, and 15 of them are now working for Sanders 2020. (The other four are spread across the campaigns for Booker, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, self-help author Marianne Williamson, and Miramar, Florida, Mayor Wayne Messam.) There are also 11 former staffers for Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley’s 2016 presidential campaign in the data set.

There’s a twofold lesson that can be derived from these staffing patterns at this point. First, there is no clear party signal about a single nominee. Experienced campaign personnel as a whole seem pretty comfortable with Biden, Warren, Harris, Booker, O’Rourke, and a few others as the potential nominee. Second, it is clear from this data and from endorsements, activist support, and other indicators who the party is not interested in: the 15 to 20 other people running.

The nomination is not as chaotic as observers might think. The party, broadly defined, really isn’t seriously picking between two dozen candidates. It’s examining five to 10 conventionally qualified members of Congress, governors, and vice presidents, much as it always has. And within that group, it’s anyone’s game.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.