Several activist groups have called out art museums for culturally insensitive exhibits or controversial board members in recent years, but few have gained as much prolonged attention as Decolonize This Place, the collective that has organized the protests at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City from last December through this May.

On May 17th, the group—its 10 core members work with organizations all over the city to plan various actions—finished a nine-week series of protests at the Whitney. The protests had threatened to overshadow the institution’s annual Biennial, which runs from May 17th to September 22nd and has itself been an occasional forum for controversial political statements in painting, sculpture, and mixed media. Decolonize This Place planned its actions at the Whitney to denounce Whitney board member Warren Kanders, whose company, Safariland, is reported to have supplied tear gas to the United States–Mexico border.

For the members of Decolonize This Place, which counts artists, art historians, and academics among its members, Kanders represents an untenable hypocrisy for an art institution that purports to present radical works. Further, they wish to draw attention to the Whitney’s profits-first mentality in its selection of board members, a problem they argue is plaguing art institutions at large.

“We can no longer accept the art-world logic of career over cause, with artists and critics making politically engaged work against the backdrop of an institutional framework grounded in the art-washing of profits for figures like Kanders,” the group wrote in a statement in February.

So far, the protest has been successful in grabbing attention in the art world, if not in persuading the Whitney to drop Kanders from its board, where he is still vice chairman. Museum Director Adam Weinberg wrote in a statement to staff and trustees in April that the museum “cannot right all the ills of an unjust world, nor is that its role.” In February, Chicago artist Michael Rakowitz pulled his commissioned work for the Biennial from the exhibition in protest of what he called the institution’s “toxic philanthropy,” exemplified by Kanders’ role on the board. By April, 120 scholars and critics were calling for Kanders to step down in an open letter to the museum; come May, over 100 artists, including some participating in the 2019 biennial, had also signed the letter.

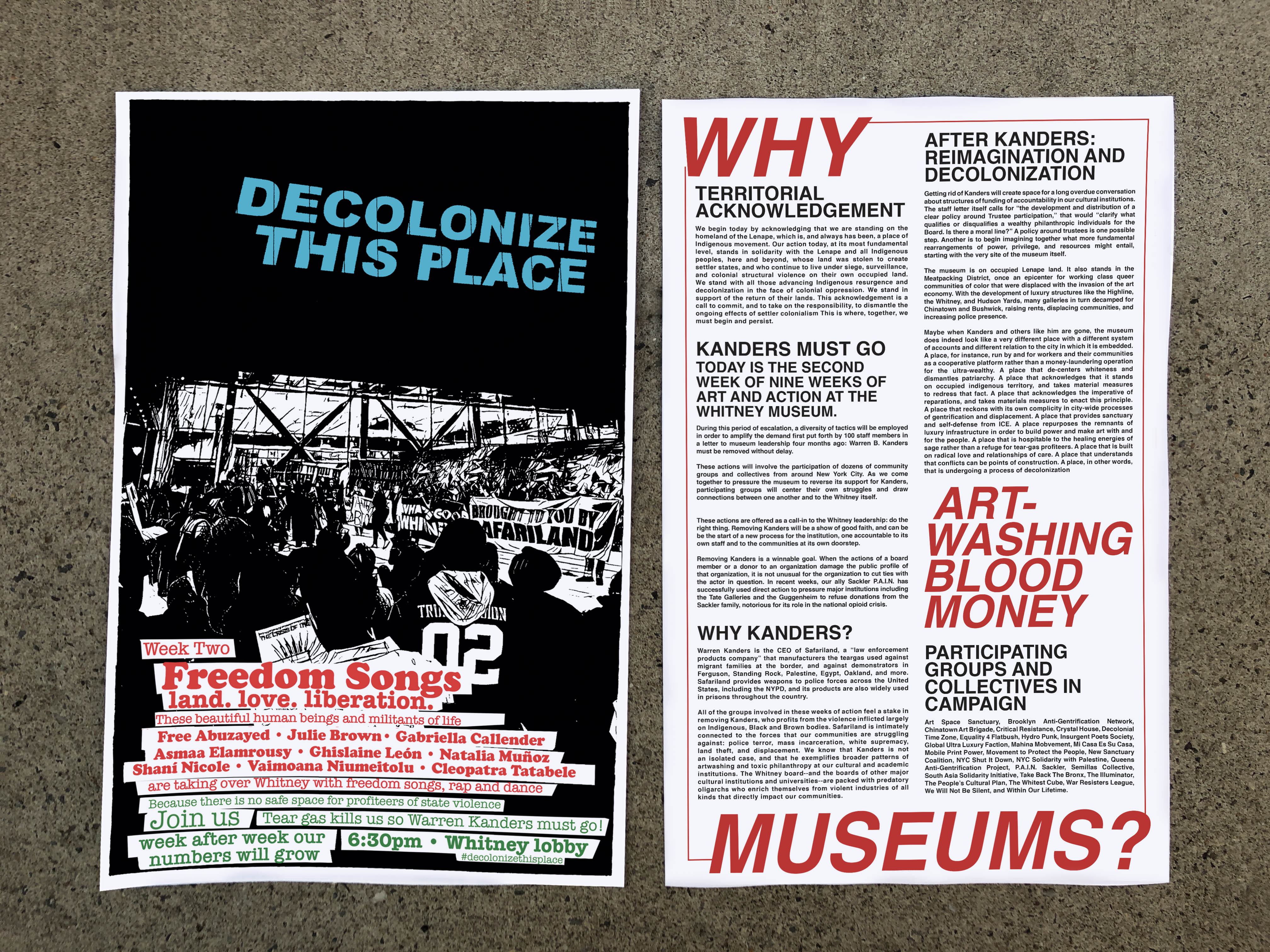

As image-heavy stories about the protests in the New York Times and various art publications have shown, Decolonize This Place’s demonstrations have been artful in their own way. One week, a partner organization for the collective, Comité Boricua, staged a dance party in the Whitney’s lobby; in the protest’s final week, protesters hung banners from the museum’s roof and marched to Kanders’ home with a sculpture of a tear-gas canister. Several posters for the demonstrations refer to places where Safariland’s tear gas has been reportedly used: Standing Rock, Tijuana, Baltimore, Bahrain. Protesters burned sage at several demonstrations, in peaceful mimicry of tear gas.

During the last week of the collective’s protest (for now; if Kanders does not leave the board, the collective says it will return to the museum in the fall), two organizers, artists Nitasha Singh and Kyle Goen, spoke with Pacific Standard about why their group targets museums, how $25 admission fees isolate art institutions as a luxury for the rich, and why the protests involved salsa dancing in addition to chanting and speeches.

You’ve said you have artists, art historians, and academics in your group. How much of your work is concentrated on art itself?

Singh: The way we think of art, we blur the lines between knowledge, action, practice, academia, and activism. I think you can say we’re about art, but we’re also [about] changing perceptions. Who defines art? Who are the institutions dominating the narrative of art?

Goen: [Art] is a part of it; it’s not the totality of what we do, but it is a large focus. A lot of what we focus on is museums: We make connections from gentrification and displacement in our community to these museums.

How did you initially come to protest Warren B. Kanders’ role on the board at the Whitney Museum?

Singh: Hyperallergic released an article about the Safariland technology being used near the border, and [about] Warren Kanders being the chair of the board of the museum. That was the starting point. The second thing—I don’t know if you know this, but War Resisters League has had a longstanding campaign around Safariland and have highlighted [Kanders’ tear gas] before it was used at the border.

On December 6th, we showed up at the museum, and people came and shared why Warren Kanders needs to go—and how, if Warren Kanders is on the board of the museum, the Whitney Museum is part of the militarization of communities. These are our communities. Then we had a town hall where artists, people who are associated and work with the Whitney, and movement groups came together to start thinking about how can we hold the institution accountable and push them to actually make the right decision. The nine weeks of action is part of that.

(Photo: Decolonize This Place)

How did the idea of doing nine weeks of protest come about?

Singh: It’s a concept that shows everybody’s commitment to holding the institution accountable. The nine weeks is about creating a space for our communities to be there—to do actions and gatherings that are also for us.

If you would come to any of these actions, you would see a variety of things, from pop-up parties to salsa dancing, things that cultural institutions should be doing. So these actions are also visionary in that way: They’re not just about negating and protesting, they’re also creating a space that doesn’t exist.

Tell me a little bit about how you conceived the aesthetic of the protest.

Goen: I do all the design work in collaboration with Nitasha and another member of the collective. When we first went to the museum back in December, the aesthetic of the posters took on the shows and art that was in the museum. So we took the Warhol aesthetic and we just ran with it.

Warhol’s aesthetic lends itself really perfectly to the work we’re doing in terms of producing a lot of stuff because there’s an instantaneous need for the work [for these protests]. We’re not making the work in a silo, spending a lot of time making and remaking and thinking about this in terms of art. We’re really just trying to get our message across and have very little time to do it. So a lot of the aesthetics are the immediacy of what we’re trying to respond to.

When you’re thinking about how to correct injustice, how does art fit into that equation?

Singh: A lot of us began as artists or academics or curators, we’re also people in art or the art world, we’re all interested in culture, but also a part of [our interest in art is that], specifically with the institutions, it’s very clear that these institutions are controlled by a lot of people who are directly impacting communities. So Warren Kanders is one person, but then also Hyperallergic recently had a closer look at the other board members at the Whitney museum, [one of whom] provides services to detention centers on the border. Also, [a member of] MoMA’s board is involved in prisons at the borders.

Art is not separate from society, art is very much a part of our society and the way it functions, but art is also a special thing where these conversations can be had much more visibly. That’s the importance of art. For me, I’m more interested in conversations that lead to action that can actually help create responsible institutions for people. People are hiding behind art institutions, and so when Kyle said that a lot of our work is part of art institutions, but a lot of work is outside of it, it’s mainly because people have thought that art institutions are separate from society anyway. These things need to change.

Why does it matter so much who is on the board of the Whitney Museum?

Goen: As artists and cultural workers, we question who’s on the board, the way they’re making their money. We make connections to our communities; the people who are doing damage in our communities are sitting on this board. It’s important for us that we question at what cost [does an] art [exhibition happen]? We actually think that institutions can function very differently than just taking money from the ultra-rich and turning everything into an ultra-luxury for a very small group of people.

Singh: These institutions are defining a lot of what art means; they are part of changing the landscape of our cities. It’s $25 to enter these museums, so who are they defining art for? That’s also the question we’re asking: It’s not just about art, it’s about our city and those who are directly impacted by [the state of museums].

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.