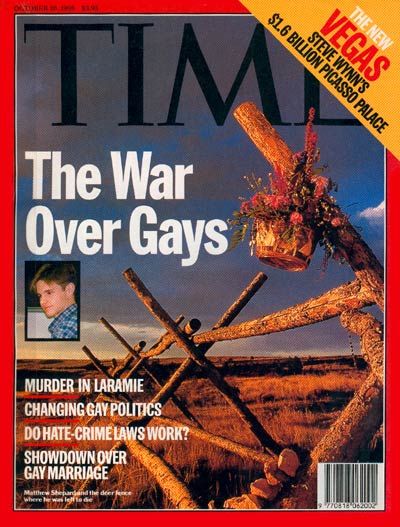

The fence was a place to hang our roses, but it’s gone now, dismantled and cast into a ravine. To confuse visitors, the roads have new names. But anyone can find the iconic photograph: the rails and wooden X’s at sunrise, shot so they tower over the rocks and dirt and prairie grass. It’s meant to look desolate. The fence’s blush among the blue of morning evokes the windchill of eastern Wyoming. Published on the cover of Time in October of 1998, what Steve Liss’ photo of the fence tries to say is, “A murder like Matthew Shepard’s must never happen again.” Ultimately, it’s a beautiful photograph. Ultimately, it can’t say anything at all.

For a long time, I believed this was America’s emblematic gay hate crime. The image of it angered me; it saddened and scared me in the way it was supposed to. Sean Patrick Maloney, the former attorney for the Matthew Shepard Foundation and a current United States Representative, has said that the murder’s galvanizing effect for gay rights recalls “what Emmett Till was to the civil rights movement.” I was too young at the time to understand, but later it meant something. Or rather, it represented something. Most familiar is the imagery: Shepard himself, a 5’2″ boyish blond found tied to a fence and covered in blood except beneath his eyes, “where he’d been crying and the tears went down his face,” as a deputy sheriff testified in 1998. I repeat this detail because it haunts me, and is meant to. Newspapers published the photo for the same reason they published the details of James Byrd Jr.’s murder that same year: because suffering is instructive. Paraphrasing the Reverend Jesse Jackson, the New York Times reported that Byrd “had entered the pantheon of the nation’s racial martyrs and victims,” and suggested “a monument in his memory as a tangible protest against hate crimes.”

Remembered properly, these murders become atrocities. Like the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting victims, like the lives lost in the destruction of the World Trade Center, these martyrs “enter the pantheon” of what I think of as prescriptive memory, whereby we, as a nation, are taught to memorialize, to say “Never Again” to such violence. Unfortunately, building memorials and planting gardens and reciting names is never enough. It’s not only ineffective, but unethical, to outsource our political engagement with history to commemorative beauty, to substitute thinking about real events with being “moved” by mere works of art.

As a slogan, “Never Again” has changed over the decades. Now attached by hashtag to nearly any protest against violence, the phrase originally referred to the Nazi genocide against Jews. As Emily Burack reports in the Jerusalem Post, “The first usage of Never Again is murky, but most likely began in post-war Israel…. The phrase gained currency in English thanks in large part to Meir Kahane, the militant rabbi who popularized it in America when he created the Jewish Defense League in 1968.” Gradually, a sense of remembrance and a desire for peace eclipsed Kahane’s militancy. “Never Again,” Burack writes, “is a phrase that keeps on evolving. It was used in protests against the Muslim ban and in support of refugees, in remembrance of Japanese internment during World War II and recalling the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.”

In a 1995 interview, discussing the Serbian slaughter of Bosnians, Susan Sontag remarked on the lack of action from other European nations, all signatories to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide: “‘Never again’ doesn’t mean anything, does it? I mean, never again will Germans be allowed to kill Jews in the 1940s, that’s true.” Despite the phrase’s apparent “universality,” when it comes to its application, Sontag is right: The phrase doesn’t stray far from its original connotation.

(Photo: Time)

Like any slogan, the power of “Never Again” erodes over time—so we pair it with beautiful images. Liss’ photograph is beautiful. The 9/11 Memorial in Lower Manhattan, with its two black pools emptying into the foundations of the towers, is beautiful. The names of victims line both fountains—an overwhelming number of names stretching illegibly far. In Chile, at the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos, there is a 50-foot-high wall covered in 3,197 photographs—the faces of Chileans murdered by Augusto Pinochet’s government. In Montgomery, Alabama, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice contains “more than 800 stele-like, six-foot-tall rusted steel mini-monuments, some standing upright, others suspended,” each, as Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, representing a county, engraved with the names of black Americans who were lynched there. As the floor descends, the coffin-like monuments begin to resemble bodies hanging overhead, “so high that the inscribed names are unreadable.”

What all these memorials do—and do well—is play upon the senses. In size, in starkness, in natural beauty, and in their mass deployment of names or faces, they overwhelm the eye. They offer emotional experiences that remind us of what they really are: art. That is, they are not straightforward records of reality, and must be approached, discussed, and critiqued as creations with artistic intent: Who made this, and what do they want me to think or to feel?

Memorials aestheticize atrocity. With their unique titles and executions, each adapts a real-life event into a complete story; often, we call them tragedies. Commemorating these tragedies we cannot change, honoring people we cannot save, memorials invite us to regard the motionless past from our mercurial present. As Sontag notes in Regarding the Pain of Others, this invitation gives our experience of the past the static quality of a photograph: “Nonstop imagery (television, streaming video, movies) is our surround, but when it comes to remembering, the photograph has the deeper bite. Memory freeze-frames; its basic unit is the single image.” Our nation’s prescriptive memory, then, with its collection of curated atrocities, becomes a gallery instead of a sequence of related events: a canon of terrible images we’re supposed to understand by looking at them.

This gallery of pain, Sontag adds, is merely “a constituent part of what a society chooses to think about,” and if you look closely at the way American society curates and archives its atrocities, you might understand our nation’s self-serving relationship to history. Not only do these memorials fail, time and time again, to deter new atrocities, but it’s starting to seem as though they welcome them. It’s hard, after all, to look at what’s happening in America these days and fear that millions of us fell asleep in the same history class, that we’ve all forgotten those weeks spent studying the Third Reich’s manipulation of resentment, their use of media, and their ascent to power. Of course, with a few swastika-waving exceptions, we have all sworn “Never Again” to such horror. Our history, we say, is linear and progressive. When the march of time is doing all the work, what is there to think about?

Americans, generally, aren’t so good at history. It’s tempting to think that our love for dramatizing wars, disasters, and other so-called tragedies onstage and in cinema has led to this perception: We catalogue our prescriptive memory via individual stories, like episodes from an epic. In episodic narratives, like Seinfeld or the Sherlock Holmes stories, nothing ever changes—everything is normal in the beginning, terrible in the middle, and resolved by the end. Characters and settings remain comfortably familiar. With real-life atrocities, this is how America has “lost its innocence” at least half a dozen times from the Civil War to 9/11. Every disaster is a “shock” to the nation. This is how our Never Again becomes Ever Again: an innocence lost somewhere in the middle of every episode, always regained before the credits.

History, after all, is heavy. “The essential American relation to the past is not to carry too much of it,” Sontag quipped in another interview. “The past impedes action, saps energy. It’s a burden because it modifies or contradicts optimism.” History, for many Americans, is something to leave behind: We say we’re post-race, and we say that gay marriage proves that homophobia is over. To do this, we tell stories about slavery and civil rights, of the AIDS epidemic. These are photos we snap and label as the past.

In truth, we are history—living it right now. Our unique pasts exist only in the present: They are with us and guide us, compass and polestar. In forsaking them for the comforting snapshots of prescriptive memory, we place great hope in what the writer and psychotherapist Adam Phillips calls a “redemptive myth.” We believe there is a “right way” to remember something, Phillips observes in his essay “The Forgetting Museum,” and “remembering done properly will give us the lives that we want.” In saying, Look what happened, we want the image itself to carry the pain, to do the work, all in a gamble we’ll recognize atrocity when and if it reappears. That, ultimately, is the weakness of prescriptive memory; even two selfies of one person are never identical. If we rely on images instead of history, we can only get lost.

(Photo: Alex Wroblewski/Getty Images)

Not that we’re always meant to find our way. Some memorials are particularly careful images of the past. Their aesthetic betrays a desired emotional, not intellectual, understanding: Viewers and visitors are meant to feel, not to think. At the 9/11 memorial and museum, the aesthetics of absence—two seemingly bottomless black pools surrounded by the names of the thousands who died—alongside recovered detritus, burned clothing, rubble, and the final voicemails of those trapped inside, all frame a narrative of destruction that points to a strangely opaque other: al-Qaeda. Absent altogether is any acknowledgment of Osama bin Laden’s long relationship with the U.S. government. To contextualize him among the names, faces, and voices of the dead—especially as a militant whom the Central Intelligence Agency had funded in the Soviet-Afghan War—would politicize something more easily remembered as tragedy.

Yet there was nothing apolitical about the destruction of the World Trade Center, and to expunge politics from the memorial is its own political act, the effect of which is to stir grief, incite rage, and mobilize Americans against an ambiguous enemy. As I write this, what is still branded “the War on Terror” approaches its 18th year, its six trillionth dollar, and the end of anywhere between half a million and two million lives. “Never Again” means nothing when victims are aestheticized as propaganda, when our own government uses them to amplify retributive terror.

Images and photographs on their own aren’t inherently deceitful. As Sontag points out, it’s the faith people tend to place in images, in their ability to speak to our sympathies, that we should distrust. “So far as we feel sympathy,” Sontag writes,

we feel we are not accomplices to what caused the suffering. Our sympathy proclaims our innocence as well as our impotence…. To set aside the sympathy we extend to others beset by war and murderous politics for a reflection on how our privileges are located on the same map as their suffering, and may—in ways we might prefer not to imagine—be linked to their suffering, as the wealth of some may imply the destitution of others, is a task for which the painful, stirring images supply only an initial spark.

What Sontag distrusts is viewing images as an end rather than as a means. Just as it’s a reader’s duty to understand a text, it is our duty—not the photographer’s or the photograph’s—to work through what we are seeing. It is unethical to expect photographs, or memorials, or images of any kind to do our prescriptive work. Instead, we must bring that work to the image. We must see it not as frozen in the past but as a shared moment from our living present—something we can respond to, even change.

Some memorials invite our scrutiny more than others. In 2017, Santiago’s Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos curated “Secrets of State: The Declassified History of the Chilean Dictatorship,” an exhibit that offered a selection from more than 23,000 American intelligence documents pertaining to Chile, including phone transcripts between Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger regarding the “threat” of Salvador Allende’s socialist government, dossiers on how to destabilize the country, and reports from the Chilean military requesting U.S. assistance with a coup. This exhibit was on display in the same building as the faces of 3,197 Chileans extrajudicially murdered by Pinochet and offers a clear link between the two. Unlike most memorials, the exhibit shows its tragedy in full context—that is, in time among other events, alongside other persons.

(Photo: Giovanni Pérez/Flickr)

Back in Montgomery, a few blocks from the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the newly built Legacy Museum offers another form of context. Progress is not the narrative here, as the Times‘ Cotter points out, but an attempt “to document and dramatize a continuing condition of race-based oppression, one that has changed form over time.” The pain remembered in the Legacy Museum is openly political, placing whiteness in context and inviting white visitors not to empathize, exactly—not to see themselves in the victim—but to recognize their own actions, their fears, in the historic oppressor. After all, it’s not the victims of political violence who get to decide “never again”; it’s those who have the power to oppress. When a memorial aestheticizes the pain of victims while eclipsing or othering the role of oppressors, viewers are unlikely to recognize their own complicity in ongoing systemic violence. Instead, we have only a finished picture, however gruesome, hung in the gallery of the past.

This is why challenging the narrative of an atrocity is so upsetting to those who connect deeply with its tragedy. This is why I began this essay with a photograph that means something to me: Tragedy can change, and we along with it.

The journalist Stephen Jimenez spent 13 years investigating the complicated circumstances surrounding Matthew Shepard’s murder, including his discovery that Shepard and one of his murderers, Aaron McKinney, not only knew each other but had had sex several times before the night of the crime, and that both had been part of Laramie’s supply chain of crystal meth. These details, published in The Book of Matt in 2013, make the murder more complicated than Liss’ evocation of an angelic martyr, not to mention downplay the murderers’ presumed homophobia. Jimenez, who is gay, has been boycotted and labeled a homophobe by gay rights organizations for writing The Book of Matt, and the book has done little to alter the cultural image of Shepard as a “crucified” angel, targeted and killed by strangers solely because he was gay.

Still, while Jimenez overlooks the likelihood that drugs and homophobia led to Shepard’s murder—McKinney refused to acknowledge his sexuality publicly and acted aggressively to those who threatened to out him—the book is a useful document in contesting the canonical narratives of tragedies, however we choose to memorialize them. After all, it’s not very instructive to say “Never Again” to some abstracted and senseless hate crime when, in fact, Shepard was a human being who suffered from depression, who self-medicated with drugs, who struggled with self-harm, and whose community failed him as a gay man, as an addict, as a mentally ill individual. So too did this same community fail McKinney, whose circumstances were very similar to Shepard’s. Sadly, work like Jimenez’s opens Shepard up to hate all over again, as exemplified by Dennis Prager’s review of the book in National Review, where he uses its premise to discredit advances in gay rights. This is the kind of hateful response gay rights organizations knew might come if journalists looked too closely at the complicated truth of Shepard’s life and death. It’s why the memory of Shepard’s murder hangs in the hall of hate crimes—even though it was never prosecuted as one.

But to flatten the murder into an unfathomable hate crime erases a more granular reality, in which drug addiction, homophobia, mental illness, rural poverty, HIV status, and the Laramie Police Department’s admitted lack of attention to an ongoing meth problem all intersected to put a young, vulnerable man at risk. It makes me uncomfortable to suggest that legislating a category of crimes based on hate is a mistake, that it immediately others perpetrators rather than acknowledges them as belonging to our systemically bigoted society. But I do know that targeting hate through slogans and foundations and beautiful photographs does not promise Never Again; it only promises not to recognize that “again” when it threatens to return.

In what is now called the Holocaust, more than six million Jews were bureaucratically murdered by an elected government. Toni Morrison’s Beloved is dedicated to the “Sixty million and more” lives lost to slavery. By refusing to acknowledge the AIDS crisis, America closed its eyes to tens of thousands of gay men who died in excruciating pain, often alone. In the single greatest act of terror in human history, the U.S. government incinerated and irradiated 200,000 Japanese civilians. On October 6th, 1998, a young gay man suffering from depression and drug addiction was tied to a fence and beaten with a .357 magnum until his brain was so damaged it could no longer keep him alive. I was 13 when this happened, and I laughed when other boys in my grade, the boys I thought I wanted to be, called Shepard a faggot who got what was coming to him. This is a shame I’ve carried since. For years, I couldn’t see myself in Matthew Shepard because he was innocently “out,” and I was criminally “in,” and so deeply that I too called him a faggot, that I said casually, in front of an adult gay couple the following summer, that fags should be more careful about who they try to flirt with. It wasn’t until I read Jimenez’s book—a book I too was furious to learn existed—that I recognized myself not only in Shepard’s self-destruction but in McKinney’s closeted violence, his willingness to destroy that part of himself he didn’t like because his culture, our culture, saw it and still sees it as a sickness.

Remembering the dead, damaged, discarded, tortured, and targeted is more than an aesthetic act. Their lives are not sacredly apolitical. Just as human beings have our overlapping diversities, so too are our atrocities intersectional. It is ethical to see and to understand the context of their pain, to recognize ourselves not only in the victims but in the perpetrators. Understood truly, every atrocity, like every photograph, asks that we recognize an “us”—never a “them.” A true politics is predicated entirely on “us.” To recognize ourselves, our actions, and above all our capabilities in atrocity brings us closer to “Never Again” than any aesthetics ever can, no matter how many people pay for the privilege to dutifully weep without any understanding of what they’ve lost, and will again.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.