Another video had gone viral. Someone wrote, “This is so beautiful,” punctuated with sad emoji. A black teenager is waiting outside a school. He’s holding flowers and balloons. Another boy emerges from the building and rushes toward him. Other students cheer as they embrace. When they finally kiss, a girl screams—she is so happy. It is a beautiful moment. It is also very sad.

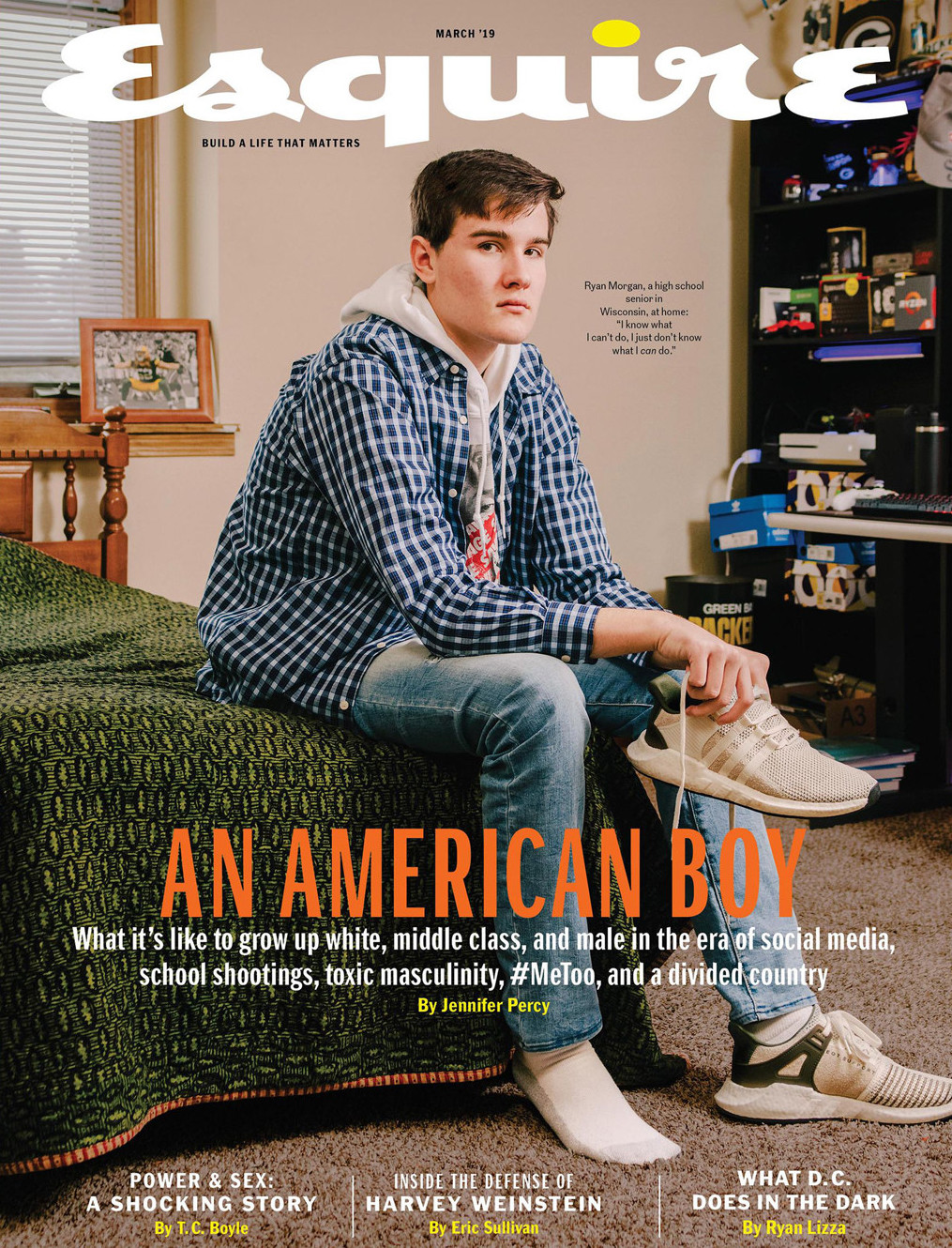

That same week, Esquire published its cover story for March: “The Life of an American Boy at 17.” Ryan Morgan, the subject of this profile, is not an American boy whom a police officer could get away with murdering. Nor is he the kind of American boy who kills himself because his parents sent him to a camp that tries to make him love differently. In fact, Ryan seems chosen almost as a provocation or dog whistle, as if to reinforce the presumed blank whiteness of the words “American boy” in a nation where many boys are not white, and in fact nothing like Ryan.

Words, though, are not blank; “American” and “boy” are not white. But it is their history, their usage, and their context in this country that makes them feel otherwise. When this history and context are overlooked or taken for granted, especially in mainstream publications, that bias can leap off the page and affect the way people live, or die. The way writing—especially journalistic writing—is taught and evaluated helps reinforce this bias. According to the mainstream criteria of journalism, Jen Percy’s article is well-written; she is almost entirely invisible. Only once does she intrude, as the author, to challenge what Ryan says—a minimizing remark about baseball player Josh Hader’s homophobic tweets. It’s the only part of the piece that stakes an ethical claim. Otherwise, Percy leaves uninterrogated Ryan’s support for capital punishment, his stance against abortion and safe sex, his misogynistic views on the social roles of boys and girls, and several other beliefs that, at the polling place where he’ll be able to vote next year, will affect real people’s lives.

Instead, we are meant to form our own opinions about who Ryan is and “what it means” for a 17-year-old straight white boy in a conservative municipality of Wisconsin to have these views.

The piece is written as if Ryan is an unfamiliar or exotic subject for profiling. In fact, he is the institutionally approved median, or neutral, of young masculinity in America, at the center of two centuries of culture, entertainment, law, education, art, and politics. America was built, mostly by slaves, for boys like Ryan.

I’ve always known who he is, because Ryan is the model I was supposed to imitate—at least until my queerness got in the way. So it’s not only insulting that Esquire assumes I can’t see him—that any queer, or any person of color, any girl or woman, can’t see him. It’s cruel. And it seems a deliberate cruelty, because all Esquire has done is to re-emphasize this neutrality, this apparent normative ideal, which makes the rest of us un-American.

Clinging to this false neutrality, Esquire has only strengthened the ideologies of whiteness and toxic masculinity. Percy may not have done this on purpose, but neither is Ryan, on purpose, a bigot whose unchallenged ignorance can and will harm other people. This is what people mean when they lament the inevitability of “the system”: Percy is doing what the system asks of her—recording what happened and who said what—and doing it well. Ryan is behaving like the boy the system wants him to be. Jay Fielden, Esquire‘s editor, is equally faithful to this system, where words are transparent and self-propagating tools of something called civilization.

(Photo: Hearst Magazines)

On the day the story was published, Fielden defended the piece and excoriated his critics, calling contemporary America a “Kafkaesque thought-police nightmare of paranoia and nausea, in which you might accidentally say what you really believe and get burned at the stake.” A debate, Fielden says, “used to be as important an ingredient of a memorable night out as what was served and who else was there. People sometimes even argued a position they might not have totally agreed with, partly for the thrilling intellectual exercise playing devil’s advocate can be.”

Later, in a public tweet that seems to have been meant as a private message, Fielden alluded to “the digital Jacobins prepar[ing] the guillotine for me.” He was referring to criticism from women, queer people, and people of color, who had spent the better part of two days articulating why the piece was so offensive, especially during Black History Month. In two parallel metaphors, Fielden equated critical resistance to his ideas with public execution—a rhetorical choice that seems in poor taste in a country where black Americans are often murdered without trials if they’re even perceived to be resisting the arguments of police officers.

For many Americans, the continued valorization of a neutral, idealized whiteness—or of a “standard” way of being a man—brings literal death. When people say, “This hurts,” and Fielden responds with metaphors suggesting that he’s the main person at risk, he creates an equivalence so disingenuous you’d have a hard time believing it, at least if you were as blind to whiteness and toxic masculinity as men like Fielden—or as boys like Ryan—seem to be.

But if you are white or cis-male or both, it is an ethical imperative for you to see these ideologies. So let’s start with masculinity:

A camera trick in horror is to layer an actor’s image on top of itself. When the actor moves, the image doesn’t quite catch up. We’re meant to think of doubles, of copies—evils to our good. In real life it’s not so different. Out here, too, we’re taught to keep up with our image, and to punish the monsters when we spot them. I was five years old when someone spotted me: “Boys don’t walk like that.” Neither did they talk like me, play like me. These were lessons. By the time I was 10, I learned how to be violent, how to use anger to be sad. I became charismatic and cruel. Rarely, from then on, did anyone see the monster beneath the image, at least until it grew too obvious and I fled to be with other monsters.

Yes, this is reductive, a fairytale. What you should know is that I write fiction; I don’t believe anyone has an innate or static “self.” What I do believe, however, is that everyone is entitled to decide how they express themselves, to have agency over the self. What is often mistaken for masculinity is policed in this way—by those who assume it has innate characteristics. This is why Ryan, for example, believes there are special roles for girls and special roles for boys. This is why I, as a child, chose to hide behind anger and aggression. To accept this image of “being a boy” or “being a man” uncritically will lead to men and boys losing agency in expressing their masculinity.

Now, whiteness:

In my early twenties, growing into a masculinity of my own, I had a type. He was thin, he was pale, he was blond or ginger or the faintest brunette. He was effeminate. In porn, so conveniently labeled and categorized, I sought this type. At bars I sought him. I ate his propaganda. I swallowed his loaded image, political in a way that took me years to understand. Like toxic masculinity, whiteness is a power structure built on hierarchies: As long as you accept subjugation in group X, your reward is to discriminate against group Y. It took me years to understand that establishing and pursuing my “type” was a way of hurting gay men of color.

The consumption and creation of images, like the usage of language, are political; every choice has behind it an ethics. There was a time in my life when I filtered black and brown men out of my porn, when my friends all looked like me. My “preference” did not enrich my life, but impoverished it. Most white gay men might not consider this act of selection to be toxic, but what could be more poisonous to an already vulnerable community? In adhering to my racially and bodily based type, I’d instructed myself that gay men are acceptable like this but not that. To me, “gay” meant white and young and fit and no one else—another imagined “neutral” that is anything but. This is where representation becomes important: We grow more fluent in our identities as we familiarize ourselves with an image vocabulary that is larger than any one self could contain.

The same week of the Esquire piece, my novel had its first anniversary. In Some Hell, my protagonist bargains with himself over which pictures of men are bad for him and which are harmless. Like most boys, queer or not, Colin can’t be himself. (Intellectually, I’m supposed to say that my fiction has nothing to do with me. It’s only art, I’ve been taught to say, as if art emerged impersonally from some other planet. Emotionally, it’s impossible to pretend my fiction isn’t me in my entirety: yes, a mirror, but smashed into thousands of independent shards.) Later, Colin looks into his future and imagines the other version of himself, the one who gets married and has a family. What an impossible person that is, he realizes, and watches him vanish. He relinquishes the boy he’s not and assumes agency over the boy he is. I write this from my own life; how crushed I was when the man I wasn’t had to die, and how relieved.

I was never supposed to write essays like this. Fiction was my landscape for imagining how to reconcile being a person; essays were for thinking. Neither was I supposed to refer, in interviews, to myself as a queer writer. That part of me wasn’t supposed to matter. I’d convinced myself that to be taken seriously as a writer I could be only an un-adjectived writer. But these two images were working to erase me, not help me. They were images the industry had chosen. My imagination had been what Sarah Schulman calls gentrified, a mentality “rooted in the belief that obedience to consumer identity over recognition of lived experience is actually normal, neutral, and value free,” as she writes in her 2012 book, The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination. Just as, long ago, my assigned image of masculinity no longer fit, I came to see this image of the “neutral writer” as a straitjacket.

For me, the Esquire piece was yet another reminder that, in America, there is no blank or neutral, not as a writer and not as a man, and that to aspire toward neutrality is to participate in your own oppression or diminution. For my part, I at least could look like Ryan (though I was shorter and, frankly, more handsome), but what does it mean for the American boys—trans, black, femme, and so on—who can’t even pretend to play the part? What they see on the cover of Esquire is pure exclusion: This is the kind of boy who matters, and boys like you do not. At the same time, the boys who do fit the mold—white, straight, and uninterested in the lives of others—are reminded that America loves them and will protect them at all costs, including costing those other boys their lives.

I began this piece with something beautiful and sad: beautiful because two boys are in love and their classmates celebrate it; sad because that was never me and couldn’t have been. There was no image I saw as a boy that convinced me it was possible. This comes down to a question of image control: Who gets to police how we see ourselves? How much authority over our expression do we surrender to TV, to social media, and to the covers of magazines? And what responsibilities do those magazines have?

What Esquire has done is not “engage in debate,” as Fielden claimed, but instead loudly shun concerns that queers, women, and people of color have raised for centuries, and that are especially pressing under the current presidential administration. Editorially, it has closed its eyes to reactionary whiteness and toxic masculinity, regurgitating unchallenged narratives that pretend these harmful ideologies are “neutral.” By refusing to connect the dots between ignorance and systemic violence, Esquire is actively policing who matters and who does not. It’s the same wound that pundits ripped open after the 2016 election, elevating and valorizing the suffering of white people, rather than focusing on the deadlier, more widespread pain of marginalized persons. What Esquire has upheld is the gentrification of American suffering, reiterating to its audience that pain and poverty and terror are irrelevant until they affect the white, the male, the straight, and the Christian.

A common lament these days is our country’s alleged addiction to “identity politics,” as if the identities of marginalized persons are what’s corroding our political discourse. For me, though, identity isn’t about how I choose to approach politics, but about how politics has confined me. My queerness isn’t something I choose to think about every day; it is an identity assigned to me by an ignorance that threatens my life. It is ethical to demand, in return, that white people think of their own whiteness, that men see their masculinity as imposed from without.

What I demand of editors is to be aware of this ethics. The stories you choose, the words you leave on the page, and the images you frame are not games; the devil already has enough advocates. These choices—about magazine covers, about representation—are decisions that contribute to how livable my life in this country can be, not to mention the lives of millions I’ve never met. These are decisions that get us killed. If this is a power you’re unwilling to use to save lives, step aside and give it to someone who will.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.