My favorite thing about Don Shirley didn’t get much screen time in that movie Green Book, or maybe it did sometime after my pal and I walked out of the theater because we had seen enough of the old gag about how white people and black people are different and ain’t that just the weirdest thing. Besides, it wasn’t like the movie was about Shirley anyway, so we bailed about an hour in and chalked up the 20 bucks each and tossed the butter-slicked popcorn to some kid walking into some other, better flick. And even if we’d stayed, I don’t think the movie would have gotten to my favorite thing about Shirley, which is not that he once sat in the back of a car, driven through the American South by someone white; not that he had endured racism and carried on with a measured calm.

My favorite thing about Shirley is that he once gave up his career as a pianist in the early 1950s, after being a child prodigy. Shirley gave his first public piano performance at the age of three and was invited to study music theory in Leningrad when he was nine. In the mid-1940s, Shirley spent his teenage years performing his compositions with the Boston Pops and the London Philharmonic Orchestra. But by the start of the ’50s, Shirley came to the realization that there might be a lack of upward mobility for black musicians with a deep investment in classical music, so he went off to study psychology at the University of Chicago, and then worked in that city as a psychologist.

Several major social forces collided in America in the 1950s. The United States population started to expand, slowly at first and then by great bounds thanks to the Baby Boom. On top of this, amid rising incomes (especially for middle-class white Americans), there were also revolutions in the domestic technology they could buy with their new money. The portable radio became a staple of the decade; televisions became more numerous and prominent in homes. As people’s access to entertainment grew, entertainment, as well, grew and changed. Anyone with access to a radio or television could consume all manner of media at the touch of a button: not only news, but also stories of crime, details of murder and theft, romance, comedy. Where the radio had once been primarily a vehicle for music, it now served multiple purposes. Between these technological developments and the sheer number of young people in the country, an organic generational gap emerged. Young people were taking in more information than had ever been available before, and it was suspected of influencing their behavior in ways that the older generation couldn’t understand.

This concern over the influence of media on young people grew into a national panic over juvenile crime, which picked up in the 1950s and became the blueprint for law enforcement’s tough-on-crime stance that we still live under today. The logic was that young people were hearing and watching stories that painted criminals as “cool,” and so they were, naturally, moved to carry out acts of crime themselves. Like most panics, the concerns themselves were rooted in a conviction that things were worse than they actually were, and that they were bound to get even worse. What will we do if young people continue to watch these stories and read these books? How will we survive it all?

This led to a different type of approach, rooted in studies of human behavior in hopes of preventing youth crime. Shirley had been out of music entirely for a few years but had been interested in finding his way back. In the early 1950s, he received a grant from researchers interested in studying the relationship between music and juvenile behavior, looking for a link that might present an opportunity to cut the growing problem short. Shirley took up residence in small clubs, planting teenagers in the audience but otherwise playing to a crowd of people unaware of the experiment he had been tasked with.

Shirley would play with sounds, measuring the responses of young people to the different combinations and compositions he put together. The audiences had no idea of the science behind what he was doing, but they were awed by his unique ear, his desire to take compositional risk, and the way he strung sounds together—as if each note were traveling the air in search of a sonic companion.

It was in this way that Shirley fell in love with music again. In 1955, he released his first album. Tonal Expressions, on Cadence records. It was a stunningly inventive album of compositions, even though it didn’t make Shirley the international star he maybe deserved to be.

My favorite thing about Shirley is that he found his way to the piano as a curious child, and never stopped letting curiosity inform his passion for the instrument. In a time of national panic about young people listening to and watching the wrong things, he set out to see if he could stem the tide of crime by playing his instrument in a small room with young people watching. It wouldn’t necessarily make for a good movie because there wouldn’t be a conclusion at the end of it all. Crime kept on happening, and Shirley went on to make records at a torrential pace for the next decade. But the mere idea of the experiment relied on a special type of musician, one who was willing to attempt the unknown, and be comfortable walking away with a problem unsolved.

I love that story about Shirley because it is the story that most reminds me of the fact that he never had to play music. He would have been fine without it. How fortunate, I suppose, that there was such a panic over juvenile crime.

Americans love to declare of things distinctly American that they are not American at all. You get what I mean, or if you don’t, wait until the next time someone commits a hate crime or shouts out something racist or otherwise bigoted during a television interview or a press scrum. Through the predictable cycles of frustration or outright rage or ironic tweets, there is inevitably a line of rhetoric lamenting “America’s original sin” with some boilerplate language about unity and choosing love over hate. These messages are often punctuated with a version of the sentiment: This is not who America is.

The actor Jussie Smollett was assaulted by two men in Chicago last month. Per his account, the men called Smollett racist and homophobic slurs before throwing a noose around his neck. Lee Daniels—producer and director of Empire, the show Smollett stars in—posted a tearful, passionate video in support of Smollett. In the video, Daniels is outside and lit by the last moments of sunlight as he balances anger with concern and compassion. At the end of his video, Daniels insists: “America is better than this.”

America, of course, is not better than this. When a nation is built on a foundation of violence, it takes an unnatural amount of work to undo every last lineage of harm and then honor the harmed parties with anything resembling equity. Some of the first steps in that direction almost certainly rely on an honest assessment of the history, and of the ways that history has generational effects.

To insist that violence and bigotry aren’t American is to continue feeding into the machinery of falsehoods that allow this country to keep making the same mistakes. There are people who talk about Martin Luther King Jr. as if he lived a long and healthy life and then chose to peacefully die at the end of it. The very concept of “choosing love” is an expression of privilege, as though there were only two options: love and hate, as Radio Raheem had emblazoned across his knuckles in gold during Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. But the very concept resting at the heart of Do the Right Thing is that all this love ain’t created equal. The love I have to give is malleable, but it has limits. All of our love has its limits, and it should. I choose to love my people, and their people. And sometimes I might also choose love with your people. But other times, I choose whatever keeps me safe, and that isn’t necessarily hate, but it might be if it gives me a comfortable enough distance.

And since we are talking about movies, after all, the whole thing I’m kicking around here is how movies have been so relentless in their quest to sanitize race relations in America, it has almost become its own genre entirely. Period pieces, usually. Some story about a time when violent racism was permeating every corner of a community, except for the one corner where a black person and a white person learned to get along by toppling the odds and seeing the common humanity in each other after being forced to share proximity because of work or love or some beneficent accident. These movies don’t really work to deconstruct ideologies of racial superiority, or examine how a country arrived where we are today. They’re films that start a few inches away from a perceived finish line, and then spend two hours slowly crawling across before throwing up hands while roses rain down from the sky.

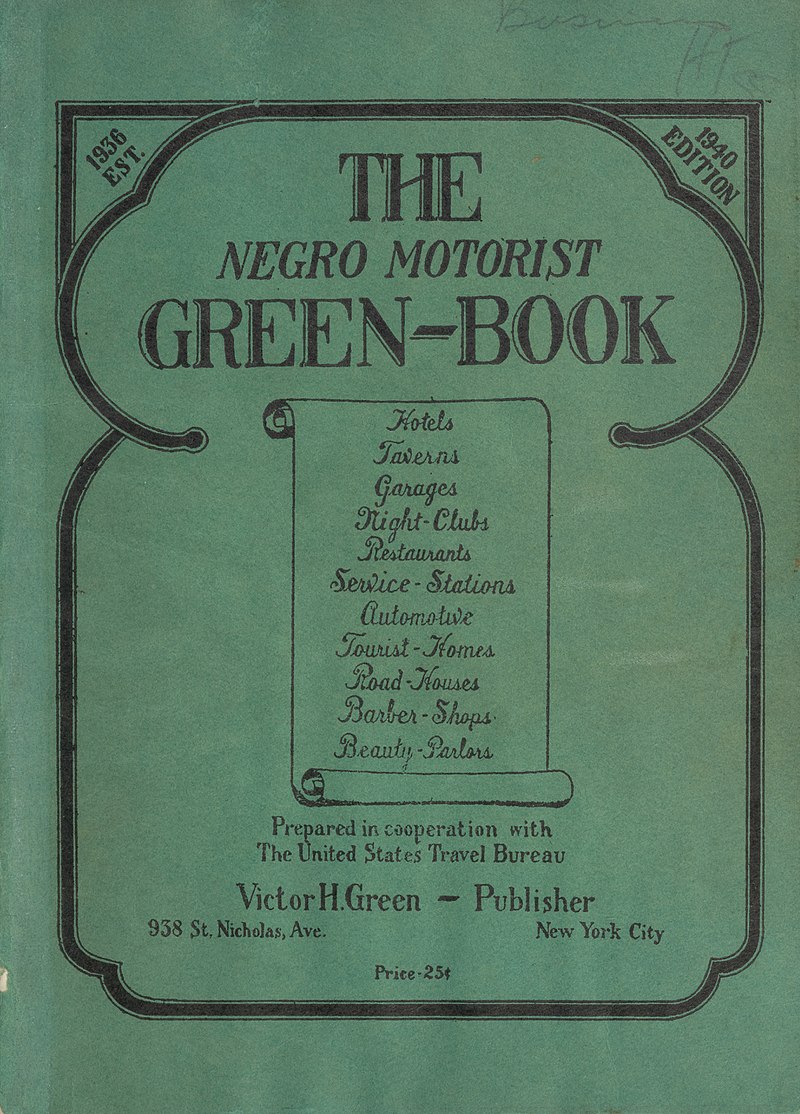

The Negro Motorist Green Book was published and updated for a stretch of 30 years, from 1936 to 1966, during the era of Jim Crow. It was initially created by Victor Hugo Green, a mailman who traveled often for his job and saw as more and more black people gained access to automobiles and began wanting to explore the vastness of the country—to chase down their version of an American Dream. For black people in America during Jim Crow, traveling meant the possibility of being denied service while on the road. Many black people who were new to traveling great distances had no guide for the rest of the country, and how they might find themselves treated in its various corners. At best, there could be an embarrassing interaction at a restaurant or gas station; at worst, there could be a hostile or violent reaction to their presence.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The Green Book started out as a small, green-colored handbook and expanded as the years went on. It was a travel guide that listed all the places where its black readers and travelers could feel safe: which diners, guest homes, museums, hotels, grocery stores would cater to them anywhere along the road, in every direction. The book spanned 300 cities in the U.S. and Canada, and relied on its readers to provide information on the various conditions wherever they traveled. It was an analog, user-created database, which circulated quietly among black homes for its entire run. At that time, there were no established interstate freeway systems in the country, and motorists had to rely on long, winding roads to get to their destinations. The Green Book was vital, alerting travelers to what towns and cities might welcome their presence, and what towns and cities they might want to be more cautious in or avoid altogether.

Of the many things America loves to pat itself on the back about, one of the things is our obsession with exploration. The Green Book is fascinating as a not-so-distant relic because it affirms that the myth of American exploration was never available or safe for all Americans.

I once found an old Green Book in an antiques store in upstate New York. It was tucked on a shelf next to old caricatures of black maids and old magazine ads with people in blackface pushing toothpaste. I was, it seemed, in the “black history” portion of the antique store. The version I found was from 1952, and, by that point, the book felt somewhat like a magazine. It had advertisements for products like skin lotion and car wax. It had promotional materials for scenic tours to enjoy while on the road. It seemed to be catering to a very specific type of American black person, one who had found a bit of financial freedom during the boom of the post-war economy and the technologies it introduced. It felt like the black people reading this book maybe believed that, if they worked hard enough, they could get the America they knew they deserved.

Of course, that made my handling of the Green Book all the more bittersweet. This book, bursting with ads, promised you the chance to invest in America like anyone else. It was filled with pictures of black travelers, grinning with enthusiasm and the rush of possibility. But even with all this optimism, one cannot ignore the grim, central function of the book, still explicitly present in many of its pages: offering routes for safe travels for black people in a country that could swallow them whole at any moment.

The movie Green Book isn’t necessarily about The Negro Motorist Green Book at all, unless one imagines Shirley’s white driver, Tony Lip, as a type of Green Book of his own, shepherding the musician through the South, fighting when he’s needed, and generally presenting a barrier between Shirley and the racism of the world. This seems to be the general idea that the film tries to sell—that anyone who stands between black people and harm is essentially doing the same work as Victor Hugo Green’s book.

But that isn’t it. In real life, The Green Book was about a communal passing of information to shepherd people to safety through autonomy—not about the intercession of a savior in the life of a single black person. The Green Book sometimes expressed hollow hope, but also operated from the fundamental understanding that no one could really save the black people reading it from the hatred they’d encounter on the road.

Even with all of the shine and gloss added to The Negro Motorist Green Book in its later years, it was still a book that served this single function. Black people have been making ways for other black people to arrive someplace safely for as long as there have been black people in America, I suppose. I stop at a gas station in one of the last cities on the outskirts of a small Ohio town, and the black dude behind the cash register asks me where I’m going, how long I’m going to be there; nods slowly and tells me what routes to take and where not to stop, even if it seems like I have to. I’m often thinking about this while driving through unfamiliar parts of the country—how I rely on the kindness of black people who know the terrain and who have, perhaps, suffered on that terrain for years before they run into me. Sometimes the warning is a knowing look, shared as I exit the restroom someone is entering, or as we lock eyes in the potato chip aisle of a gas station. The physical, hard copy of The Green Book was needed less urgently, it seemed, as civil rights laws went into effect and highway systems began to develop. But the actual, living problems that The Green Book addressed don’t ever vanish, not as long as there are still places in America where black people are less safe. The work of The Green Book continues, among black Americans who understand where they’re from and are careful to alert others what those places are and aren’t capable of accepting. Some small towns rely on black people to do their most public-facing labor: cashiers and front desk attendants and clerks of all sorts. The new version of The Green Book is a conversational network that echoes from one person to the next, until a clearer, kinder path of road is carved out.

And the need for this type of network may never change. Funny, to see a movie bearing the name of an iconic text that helped black people realize their own dreams of safe travel and American exploration. Funnier, I think, that such a movie exists in a time when black people still must exercise ingenuity to make safer pathways through remote parts of the country. Green Book is the type of movie that allows people in America to think about all the gentle ways racism can be waved away, and, for that, it is adored. Shirley died in 2013, but his family spoke out against the movie’s release, and against the acclaim it’s continuing to receive. They’ve taken issue with the movie’s story overall, and in particular with its representation of Shirley and Lip’s relationship. Shirley had viewed Lip as an employee, his family said—someone tasked with driving him around, and not much more. Of course, the family’s resistance to the movie didn’t stop the plaudits from rolling in. The black relatives of Shirley had to make room for the coronation of the film’s white creators—one of whom is Nick Vallelonga, Lip’s son.

That’s just the way it goes, I guess. The easy part plays well. The people who loved The Green Book got to feel good about their America for a little while, and with enough of those good feelings strung together, it might be easy to forget that there ever was a fire, that the fire, in fact, is still burning.

My favorite thing about Shirley is not that he was a genius who led a sometimes-spectacular life. It is that, in the moments in between, he likely led a life that was very normal. And that is spectacular too.

What I want is a movie cast entirely of the unspectacular but still happily living black geniuses, who have pointed me on a safer path out of the goodness of their own hearts. Perhaps scenes in whatever clothes they wear after they take off their Sunday best. I want them to be absolved, but no one else. I don’t want anyone to watch this movie and consider themselves clean. Everyone else will have to earn it.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.