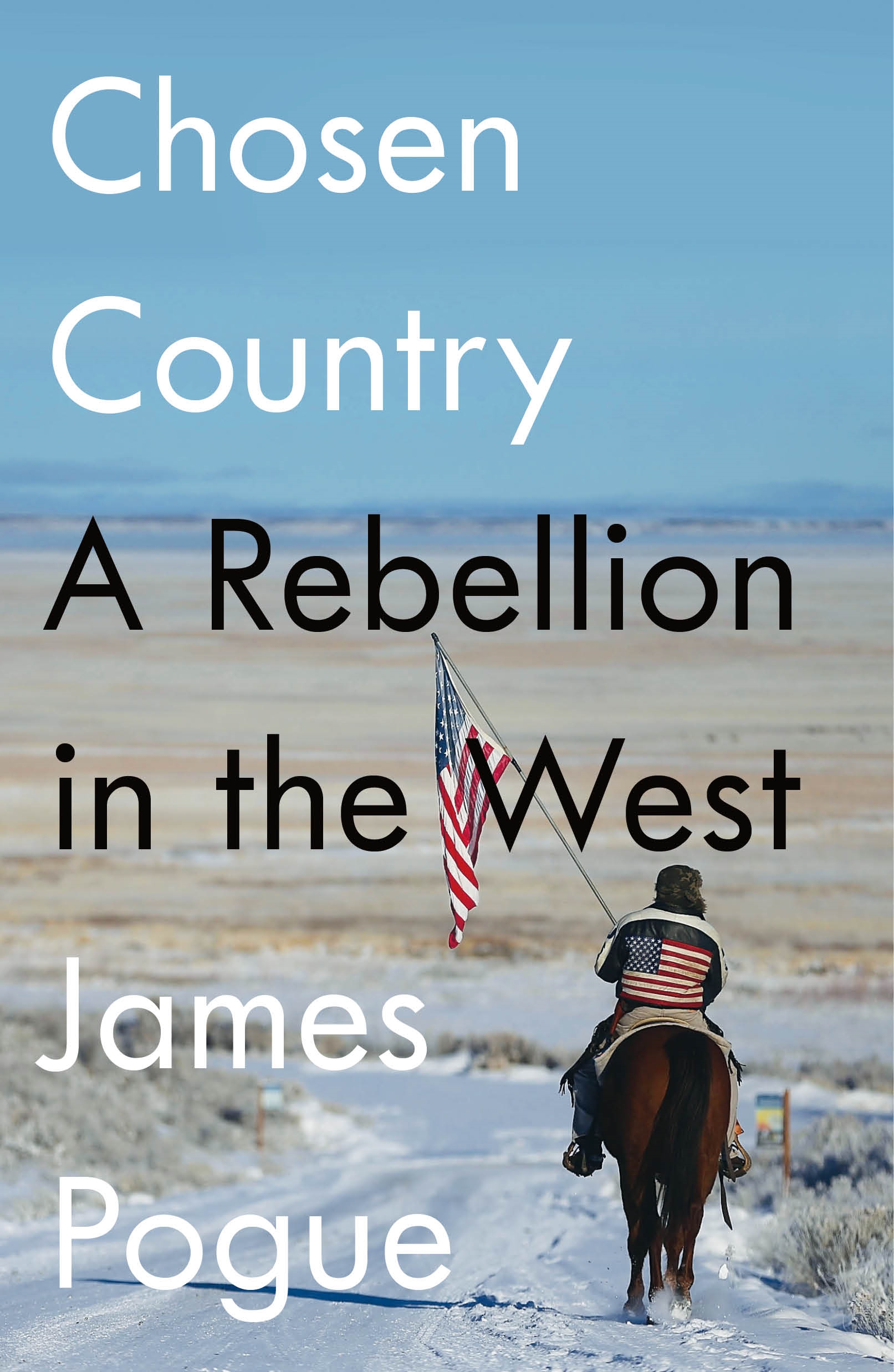

(Photo: Henry Holt & Co.)

Chosen Country: A Rebellion in the West

James Pogue

Henry Holt & Co.

In early 2016, the writer James Pogue finagled his way behind the scenes at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon, not long after it had been taken over by a crew of anti-government agitators loosely led by Ammon Bundy, a charismatic small businessman with messianic delusions. (Not to be confused with his father, the rancher Cliven Bundy, who holds similar beliefs, and who, in 2014, staged an armed standoff with federal agents in Nevada over his refusal to pay grazing fees for his cattle on federal land.) Embedded at Malheur, Pogue spent long, jittery days and nights in close quarters with the occupiers, trying to understand their worldviews, which mixed libertarianism, a resentful sense of cultural exclusion, nostalgia for a bygone West that only ever partly existed, and guns. Lots of guns.

Pogue’s trip yielded articles for the New York Times Magazine and Vice. Citizen actions, even violent ones, over land ownership and management in the West weren’t new, but in 2016 they stood a higher chance of making national news. Donald Trump’s Republican primary campaign was drawing far-right extremists out of the woodwork, prompting a national conversation—still ongoing—about how to re-conceptualize the relationship between the mainstream and the extreme, the “normal” and the “marginal.”

Journalism, as the old saying has it, provides the first, rough draft of history. The Trump era, especially in its earliest days, produced some horrible rough drafts: wide-eyed newspaper profiles of self-described fascists that would have been at home, tonally, in glossy celebrity magazines; coverage of avowed white nationalists that was low on insight and high on naive shock at the idea that real-life racists might look like actual people, not cartoon Third Reich re-enactors.

(Photo: William Widmer)

Chosen Country, Pogue’s book-length treatment of the Malheur saga, is an intriguing document of our times: reported mostly while Trump was a long-shot candidate (but still a handily plausible news peg), then written, or at least revised, when he was commander-in-chief. It’s a second draft of history, let’s say, one that captures the author’s attitude toward his material as it’s still evolving.

It’s also not straight-ahead journalism, but rather a New Journalism-style first-person report on what it was like for James Pogue, writer, to be on the scene. Much of the background—about the Bundy family and its libertarian brand of factional Mormonism; about militias like the Oath Keepers and the Three Percenters, whose numbers have grown explosively since the beginning of the Obama presidency; about some Westerners’ resentment of the Bureau of Land Management—is readily available in existing reports. At times, the contextual passages feel tacked on, as if Pogue finds them less compelling than the adrenaline bath of the occupation itself, the rush of being there.

Many an unsuspecting reader will likely be puzzled by how much space Pogue spends on Pogue: his alienated upbringing in Cincinnati; the gradual development of his own attachment to the Western landscape; the drift and anomie that overtook him in the years before the occupation; his intense drinking and drug use. As a narrator, he’s a bit too keen to project an image of himself as a Hard-Edged Intellectual Wildman. He has a grating habit of referring to adult women as girls.

But Pogue’s presence on the page as a flesh-and-blood character (albeit a frequently annoying one) is not without advantages. For one, he gets to express some touchingly full-throated gratitude for public lands and the “sense of possibility far beyond the bounds of [our] immediate existence” that they provide, even if you’re in a city hundreds of miles away.

Just as valuable, he’s not beholden to conventions of straight-faced journalistic neutrality. In the field, he commits to listening to the occupiers’ stories, searching beneath their bluster and posturing to identify commitments and grievances that they might be able to agree on. But on the page, he’s perfectly willing to push back. The Bundy camp’s interpretation of the Constitution is laughably incorrect. Their vision of an ideal America is unavoidably white at best, and aggressively racist at worst. Their agenda, though wrapped in the language of frontier individualism, dovetails with the wish list of massive corporations that hate federal land because they want to plunder it for profit. Ammon Bundy doesn’t really stand for anything, Pogue suggests, other than the idea of “making a hard stand.”

(Photo: Matt Mills McKnight/Getty Images)

Pogue is upfront in admitting that, like many at Malheur, he was drawn there by a hunger for “easy adventure” and dissatisfaction with his own “drug-addled routine of wild drinking and manic dating.” It’s clear that, at Malheur, he experienced the thrill of making contact with a wild margin of American life. Equally clear is the pride he took in being a good listener instead of a stereotypically aloof or condescending member of the liberal media elite. But as the book goes on and the occupation ends, Pogue the writer becomes increasingly skeptical about Pogue the adventure-seeking reporter, wondering aloud about the ultimate wisdom of his approach. His adventure is over, and the Oath Keepers’ candidate of choice, Trump—himself once dismissed as an entertaining curiosity by the press—is sitting in the White House.

This self-doubt culminates in the book’s final lines, in which Pogue cuts short a jailhouse interview with Ammon Bundy. (Ammon would eventually be acquitted for his role in the Malheur standoff, and prosecutorial misconduct would lead to the dismissal of charges for the part he played in the Nevada standoff.) “It took me maybe longer than it should have to realize this,” he writes, “but there’s a point when trying too hard to listen to someone who has no plan on listening back stops feeling like a search for understanding and starts to feel like a surrender. We’re all learning this now.”

This sentiment casts an unflattering shadow back over much of the preceding 200-odd pages. I found myself thinking of the passage in which Pogue, attending a press conference in Oregon, makes offhand reference to “a skinny young man named Alex, who’d been involved in anti-militia organizing long before the issue made it into the news.” That’s the last we hear about Alex, or really about anyone else (besides James Pogue) who expresses love of the West without reaching for an AR-15. After leaving Malheur, Pogue could have sought out Alex and more people like him, asked about their work: why they do it; what it has and hasn’t accomplished; what they’ve learned. Absent such perspectives, Chosen Country ends on a paradoxically eloquent expression of its own incompleteness—perhaps not the insight many readers will have come to Pogue’s book looking for, but an insight nonetheless.

A version of this story originally appeared in the May 2018 issue of Pacific Standard. Subscribe now and get eight issues/year or purchase a single copy of the magazine.