If the string of male superheroes at the multiplex is an indicator that comic books are still a boys’ club, the fast rise of Kelly Sue DeConnick provides a spark of hope that times are changing. The widely acclaimed writer and editor published her first comic story in 2004, and though she earned some attention for her work on 30 Days of Night: Eben & Stella and a few Marvel one-off graphic novels, it was her 2012 reboot of the former Ms. Marvel, Carol Danvers, as Captain Marvel that gained DeConnick mainstream recognition. Replacing Danvers’ customary bikini costume with a space commander’s uniform — and teaming her up with an all-female squadron — her work inspired fans to organize Carol Corps, a community that has advocated for diversity (especially female lead characters) in comic books. DeConnick has since written two anthologized series for Image Comics: Pretty Deadly,a poetic Western that features a woman as a legendary warrior; and Bitch Planet, a dystopian prison story that doubles as feminist commentary. She is currently developing the television series Redliners, based on a book of short stories by True Blood author Charlaine Harris, for NBC.

Course

An Introduction to Formal Logic

Last year, researchers studying the misinformation on social-media sites called those platforms an echo chamber for bad science and conspiracy theories. How, then, can those of us on Twitter and Facebook — that’s over two-thirds of Americans — separate the good posts from the bad? An Introduction to Formal Logic, from the audio and video college-course series The Great Courses, promises an “intellectual self-defense” against unreasonable statements in a mobile, easy-to-use form. DeConnick says she’s been watching this particular course, taught by Gettysburg College professor Steven Gimbel, while on the treadmill.

Why

“I’ve been thinking a lot about this culture that we’re in of people just screaming at each other on the Internet, and how what we call debate isn’t really debate in the way that I learned when I was in high school. We seem to speak at each other rather than trying to make convincing arguments. I would like to understand, when someone says something is a straw-man argument, what’s the formal definition of that. Let’s go back to fundamentals of rhetoric.”

Comic Books

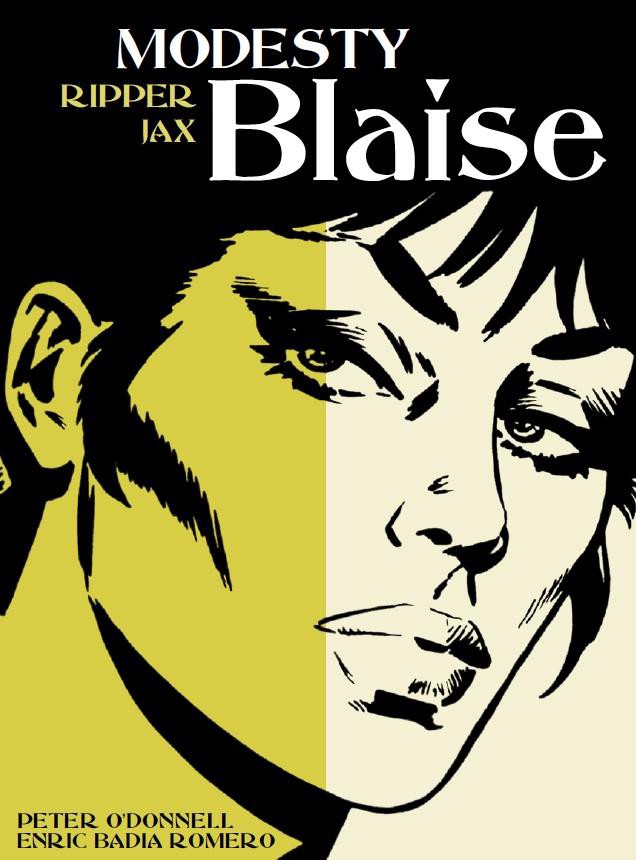

Modesty Blaise

By today’s standards, British comic heroine Modesty Blaise’s origin story seems like pretty standard fare: Orphaned as a child, she becomes the leader of a Moroccan crime syndicate, retires early, and subsequently uses her wealth and combat know-how to fight crime in London. But in 1963, when she was created by writer Peter O’Donnell, Modesty was revolutionary simply for being a woman. “I thought it was about time someone came up with a female who could do all the things the males had been doing,” O’Donnell said in a 1966 interview. (The Daily Express, which originally commissioned the comic strip, thought otherwise, canceling it because the character wasn’t living up to her namesake noun; The London Evening Standard picked it up instead.)

Why

“As someone who makes their living in genre fiction, I have such a strange and difficult relationship with characters like James Bond. So many of the films that I loved when I was younger, when I watch them with adult eyes it’s hard not to see the sexism and racism in them, and it’s hard to enjoy them. Modesty Blaise is certainly not perfect, but she is a woman with agency and she has swagger that women are generally not allowed to have. She is this central, ridiculous romantic heroine in the way that James Bond is.”

Cook Korean! A Comic Book With Recipes

What happens when a Korean-born cartoonist and illustrator moves to Brooklyn and learns there’s no Korean food in her neighborhood? In the case of cartoonist and illustrator Robin Ha, it meant placing a phone call to her mom up to ask for simple recipes — and a subsequent comic book sharing what she learned. The result includes several vibrant illustrated guides for making quick, easy-to-learn basics, from bulgogi to kimchi to seaweed rice rolls.

Why

“It has made me think that all cookbooks should be comic books. Because comics are such a visceral language, it feels like someone is teaching you in a really personal way. It’s also utterly delightful and beautiful to look at — lots of greens and yellows and reds in the drawings. I’ve never cooked anything from it, and I don’t care. It’s so, so cool.”

Art

Germania

It wasn’t until Hans Haacke accepted an invitation in 1993 to create one of his famous conceptual artworks at the German Pavilion at the Venice Biennale that he learned about the building’s sinister origins. Originally conceived to resemble an ancient temple, the German Pavilion was redesigned in 1938 by the Nazis to reflect the aesthetic of the Third Reich. In an act of long-delayed comeuppance, Haacke then tore out and smashed the marble floors that Adolf Hitler’s workers had installed, and named the exhibit, ironically, after the title Hitler wanted for Berlin after his expected victory in World War II (which, of course, never came about).

Why

“I felt my breath leave my body. It was silent as I walked around, except for the scratching and crumbling of the broken bits of cement beneath my feet. And I had a sense of a country struggling with itself, torn down, and there was a sadness. I’ve been thinking about that piece since we started talking about Aleppo, and the culture wars that we’re having in this country right now. I’ve been thinking about the kind of destruction I felt in that room, and the way I felt this visceral experience of a nation destroying itself.”

Sculptor

Do-Ho Suh

A South Korea-raised sculptor who left home for art school in the United States, Do-Ho Suh often incorporates themes of identity, displacement, and migration into his site-specific installations: In Fallen Star, a bucolic one-story home perches on the edge of a seven-story building as if it has crash-landed there, while in Cause and Effect thousands of identical, translucent men stacked on piggyback constitute a tornado.

Why

“[Cause and Effect] makes me think about how each of us is a small part of a larger picture, and how we’re each an important thread in the tapestry, and, if our thread comes out, it’s no longer whole. That we each have something to say and something to do and some element of support to give. It’s a very warm feeling I have reacting to this piece. I don’t know what it would feel like to see it in person, but it was very effective and kind of made my heart beat a little faster just looking at the photos.”

Short Film

The End of Eating Everything

Kenyan-born, New York-based artist Wangechi Mutu directed her first short film in 2013, to accompany a retrospective of her work — which included painting, sculpture, and installation — at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke. Starring musician Santigold (Master of My Make-Believe, 99¢), the film follows a flying creature as it navigates the skies, motivated by hunger to eat everything it encounters — a scenario that, Mutu says, expresses that consumption is a “state of mind.”

Why

“I saw this at Duke University. It was strange and mesmerizing and surreal, horrible and wonderful at the same time. It makes me think about the nature of hunger and consumption, and making things a part of us. And I find it strange and compelling and also funny — it makes me laugh, too, for no reason that I can articulate. I like that.”

Dance

This Cordate Carcass

In a piece inspired by the life of artist Frida Kahlo, choreographer Llory Wilson intermingles themes of confinement, disability, and strength into a 75-minute abstract performance. Two solo dances incorporate braces and crutches; one memorable moment sees her dancers hanging from 12-foot copper poles like flags. “I think it was the first time I had ever seen anyone strong enough to do something like that,” DeConnick says, “And that was a transformative moment.”

Why

“I find that film biographies often seem to be failures. It’s hard to distill a life down to two hours, it never really works, because we don’t live one story, we live thousands. This was a visceral experience of someone’s artistic life that was non-linear, and a portrait in moving pictures in a way that films never are.”

Band

Thee Michelle Gun Elephant

True to the band’s name (which comes from a former member’s verbal jumbling of The Damned’s album Machine Gun Etiquette in broken English), Japanese group Thee Michelle Gun Elephant made British and American punk and rock styles their own. “What little the West has heard from Thee Michelle Gun Elephant sounds like an advertisement for The Second Coming of Rock,” Paper magazine once wrote about the band, which was active from 1991 to 2003. DeConnick came across the group while working on an English-language adaptation of Taiyo Matsumoto’s Blue Spring — Thee Michelle Gun Elephant wrote the soundtrack for the film adaptation.

Why

“It makes me feel that 16-year-old go-fuck-yourself rebellion that, as a 46-year-old woman, I don’t so much feel these days. It makes me want to run so fast I fall down. Also it makes me want to smoke cigarettes, which is really bad; I haven’t smoked cigarettes in a really long time. But it’s the kind of music that makes you want to smoke. It’s very garage-rock.”

Documentary

Six by Sondheim

HBO’s celebrated 2013 documentary about legendary Broadway composer Steven Sondheim is, befitting its subject, part conventional talking-head documentary, part performance piece. Combining interviews with the subject about his life and work with performances of six of his most beloved compositions, the film offers viewers a glimpse into Sondheim’s practices for writing lyrics and telling biographical stories.

Why

“I was surprised by how much overlap I felt in the kind of storytelling I do and the kind he does as a lyricist. The way he talks about the meter and the certain line to fit the story into, it reminded me of the way we have a visual meter. We have only so much space that we can put words in, and we don’t overwhelm the art with the words, and we don’t want to tell you what you’re looking at. There’s a puzzle-solving capacity to it that’s very, very similar — I was really struck by that.”