Across from the fishing wharfs that abut Main Street, the Stonington town hall sits in a clapboard building with a mansard roof, slabs of granite for steps, and a view of the North Atlantic. When I arrived there one afternoon in late spring of 2014, the lobby was unlit and empty, save a corner with a few chairs and a bookshelf that held sheaves of blank applications. There were applications for licenses to dig for marine worms, applications for subsidized heating oil, applications for general assistance. Above all the papers, someone had tacked a list of privately owned islands whose owners permitted public access—Apple, Potato, Weir, Wheat, Crow. The islands felt like Maine itself, quietly divided and understated to the point of exaggeration.

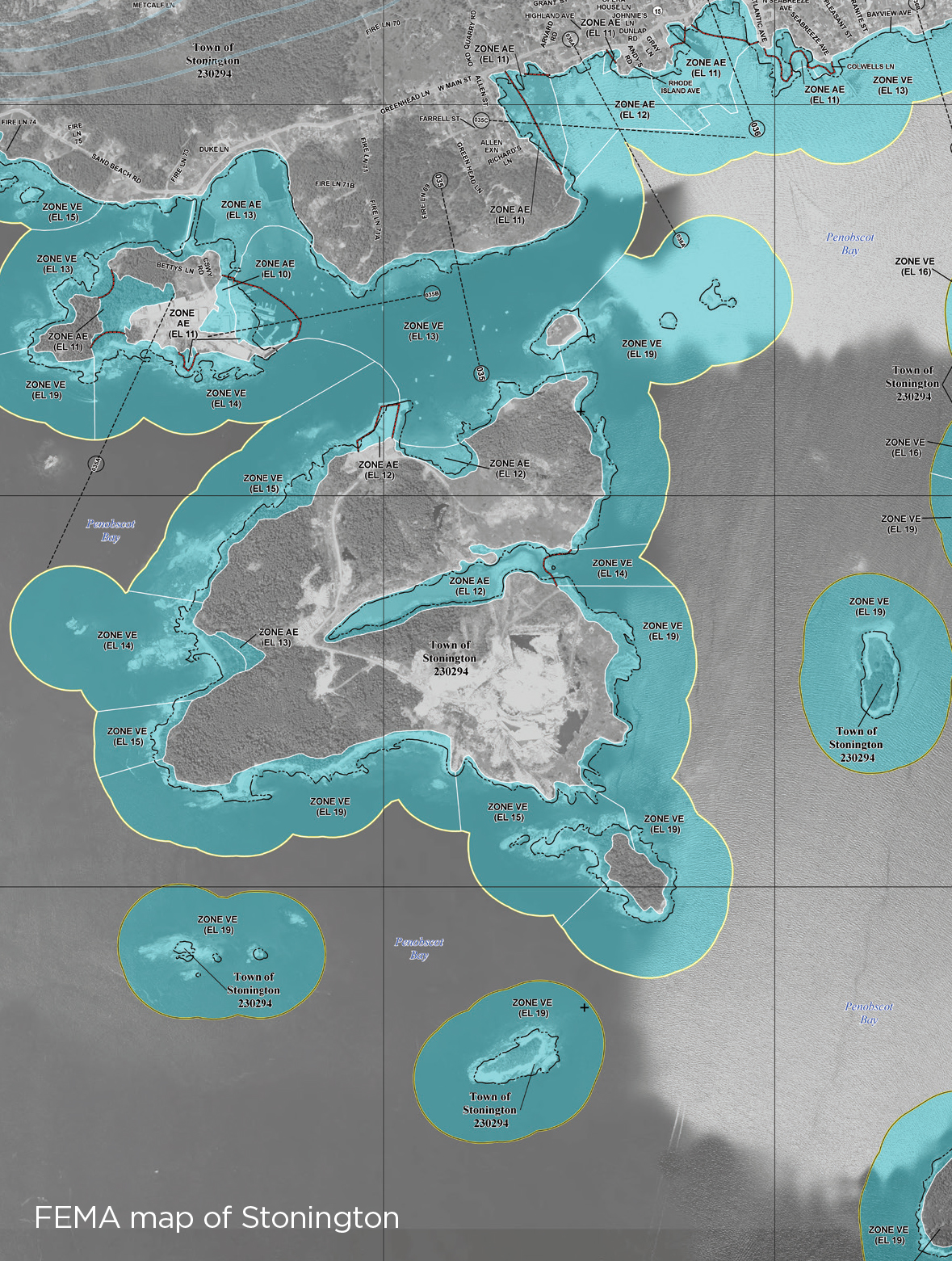

From an office, the town manager emerged, a tall, reserved woman named Kathleen Billings. She had a short thatch of nutmeg hair and wore a T-shirt with mountains and Harley-Davidsons silkscreened across the front. Walking to the hall’s break room, she immediately began to tell me how worried she was about Stonington’s future. She said local officials had recently learned that updated maps from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which determine who is required to pay for federal flood insurance, showed large swaths of land newly within the floodplain. Everyone knew the maps were coming, Kathleen said, “but I figured it’d just be something a little more accurate, a little more refined. I didn’t expect it to be so extreme.”

We sat down on either side of the break-room table, its surface covered in floodplain maps. A few had been fanned open, corners weighted down by stained coffee mugs and unopened cans of soda. The rest were rolled into tattered cylinders. It looked like the staging area for a small, old-fashioned war.

Kathleen acknowledged that the old maps were overdue for an update; it was 2014, and many of the maps were 30 years old or more. In the wake of Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy, as it became clear that storms were getting more intense and more frequent, FEMA had subcontracted private firms to redraw coastal floodplain maps. Some of the changes were inevitable. In recent decades, data showed storms battering the coast with increasing intensity, and GIS mapping technologies were light years from what had been used to draw the original maps. But other changes, town officials and residents argued, made no sense—not just in Maine, but in every place surveyed for the redrawn maps. In some cases, the new floodplain included properties perched high on hillsides and cliffs, nestled in protected coves, or sheltered by islands.

Over time, the updated maps could cost Stonington’s residents and business owners hundreds of thousands of dollars in new insurance fees, lost commercial zoning along the waterfront, lowered property values, and lost tax revenue. Kathleen said it would be one thing if the maps appeared to be accurate, but many details about these new maps seemed off, especially when it came to predicting how waves would arrive at the shore. She reached out her hand and made a circle over a stack of the new maps like a weatherperson explaining the path of a hurricane. “These are truly a disaster,” she said.

“Communities may choose to provide additional information at any time to update and maintain the flood studies,” FEMA said in a statement. “This does not mean that the studies performed by FEMA were inaccurate. Rather, locally provided supplemental data are necessary as conditions on the ground change.” But the federal government refused to pay for corrections, or even to reimburse for them, which meant hiring a private consultant and paying out of pocket—as an individual or as a town—was the only way to request changes. In Maine, the southern coast is known not just for being more densely populated, but for its concentration of wealth, and people there were particularly proactive about protecting their investments. After the initial batch of maps was released in that region, eight of the towns jumped into action, convening public meetings and contracting private consultants to carry out more detailed simulations of how a 100-year storm would hit, and challenging the FEMA predictions—with great success.

In fact, FEMA had accepted nearly all of the appeals submitted in Maine by Bob Gerber, the most popular—almost the only—consultant used by the towns that had decided to contest the new maps. A geologist and Massachusetts Institute of Technology-trained engineer who’d grown up on the coast of Maine, he now had a summer home on Isle au Haut, one of the islands off the coast of Stonington. Over the years, he’d spent plenty of time in the area and was well-known by city officials. He’d even provided some preliminary advice free of charge. And if the town opted to use his services, he had promised to keep his fees as low as possible. Nonetheless, those costs were likely to run upward of $25,000.

Stonington is remote and still largely working class, a place where many locals, as the stacks of assistance forms make clear, struggle just to cover basic needs. It’s a place where $25,000 is real money. While Kathleen strongly believed amending the maps was the town’s best shot at remaining viable as a working fishing village, convincing the community to allocate funds would be hard.

The meeting where Kathleen would attempt to do so was in a few hours. She thumbed open a diet soda and took a long draft. “I don’t know what we’re going to do,” she said.

(Photos: Bob O’Connor)

(Photo: Bob O’Connor)

People from other states have always owned summer homes in Maine, but, in recent decades, this has become increasingly common. The southern border of Maine is less than two hours from Boston, five from New York City. In the 1980s and ’90s, urbanites with good salaries and flourishing investment portfolios realized they could buy second homes in Maine for a song—and they did. As a result real estate prices and property taxes climbed, and working-class Maine families began moving away from the coast.

I was born and raised here, in an old farming town that might be described as poor if not for the fact that such a description would offend all of us who call it home. My father was not a fisherman, but a construction foreman; we lived 10 miles inland. Yet we belonged to a school district of five small towns, two of which had traditionally been fishing villages, and I remember riding the bus to school, wondering at piles of lobster traps that began showing up around houses nearby, far from the coast—the gear of displaced fishermen.

Today, 88 percent of the Maine coast is privately owned and, according to the Island Institute in Rockland, less than 20 of the state’s more than 5,000 miles of coastline remain working waterfront. Much of that private property is vacation homes, used a few months of the year. In fact, according to the 2010 United States Census of Housing, nearly 16 percent of Maine houses are second homes, more than five times the national rate, and the highest rate in the U.S. But while longtime Mainers may grumble about “summer people,” the economy soon adjusted to the new reality. At the very least, more visitors meant more tourism dollars. Even in towns like Stonington, where the fishing industry hung on and even thrived, Maine’s coastal economies grew ever more dependent on tourists and the industries devoted to serving them. The “Vacationland” slogan adopted for the state during the cash-strapped Depression years had become a stark reality.

So when the American housing crisis hit a decade ago, it was particularly devastating. The collapse brought a huge drop, not only in the building and real-estate industries, but also in tourism. Most coastal towns were deeply affected—and were just starting to get their footing again after years of slow recovery when the redrawing of the FEMA maps was announced. After 15 years living away, I first heard about the plan a few months before moving back and was caught off guard by how political and contentious the process became and how it seemed to highlight the state’s ever-widening income gap. FEMA began its remapping along the southern part of the state, then gradually continued northeast. Places like Portland, Cape Elizabeth, and Scarborough have some of the highest property values in the state, and residents there quickly hired consultants to battle the changes. They succeeded in having the whole approval process for southern Maine postponed so maps could be evaluated in even greater detail. Today, four years later, the maps there remain on hold, with the older, less restrictive maps still in effect—staving off new costs and economic impacts, at least for now.

Meanwhile, FEMA continued up the coast. Updated, more restrictive maps were released, and in many cases approved, for other parts of the coast. Some of those towns have also contested their maps and halted the process. Some have not. Because the mapping process hinged not only on environmental science, but on who could afford the costly fight, it essentially created two competing maps: a more detailed, more accurate version for people with more money, and another, likely less accurate version of the coastline for those with less.

No one understands the disparities of the Maine coast better than Bob Gerber. “FEMA is doing more detailed studies for areas where there’s more potential for loss,” he told me bluntly, “which is also where people have the money to contest the maps.” He was piloting an old Jeep down an uneven dirt road toward his home on Isle au Haut. Bob, who was in his early sixties, had a flop of white hair and a blunt way of speaking, as if words were numbers and sentences equations, impossible to mess up so long as they were correct. His Maine ties go back to childhood, he said, growing up on an island near Portland, where he’d been deposited along with his sister and their single mother when Bob was four or five. Bob’s father, a traveling salesman, was already married to another woman in Massachusetts, with other kids, and decided a scrappy island in Maine was a good place to keep a second family.

“I can mix as easily with the local fishermen as with the people out on the Point,” he said. I laughed; I didn’t need to ask to know that the Point was a summer community. He cracked a smile and offered to change into a Down East accent as proof.

Eventually Bob’s mother moved the family to the nearby town of Freeport to live with an aunt and uncle of hers. Today the town has become an enclave of expensive waterfront homes and shopping outlets, built up around the flagship store for L.L. Bean, but in the 1950s and ’60s, Freeport was a village, home to fishing families and a small tribe of white people wealthy in the dry, mannered way of old New England money. Although Bob’s own family had little, some of his friends belonged to the local yacht club and often invited him sailing, which cemented his love of boats and the Maine coast.

Over the years he’d become a living repository of anecdotes about sailing and kayaking in Maine. One day he showed me a collection of ships’ logs obsessively detailing all the weather he’d encountered over the years on particular stretches of water. Another day he played a mixtape of ocean-themed songs he’d made, which included everything from sea shanties to the Beach Boys’ “Kokomo.” Sometimes, he said, after riding out a particularly bad storm on the boat, he liked to bring his stereo on deck and crank these songs as he cruised into port.

Even as a college student, there had never been any question about wanting to return to the coast of Maine. To him, it was endlessly fascinating.

“When people ask me what I do now, I say I model environmental systems,” Bob told me. “When I work I like to think of when I’ve been in all these places along the coast. And I ask myself: These waves, in this place—how do they act? How might they act in the future?”

In most cases, Bob said, a site visit wasn’t necessary to remap an area. He had all the software and already knew the peculiar features of the shoreline—such as the vertical granite walls lining the coast in Stonington—which are nearly impossible to interpret via aerial maps. But often Bob would take his boat out anyway, riding the length of the shoreline, examining how it looked and how it currently was or wasn’t eroded and washed out. Then, at home, working in a program called ArcGIS, he would collect aerial data, along with the files FEMA used to make its maps, and start looking at where FEMA had placed its transects, which are a series of lines that run perpendicular to the shore and correspond to specific points on land. The more transects, the more accurate the map. Bob says the poorer and less populated a town, the fewer transects FEMA tended to do. FEMA disputed this claim in a statement to Pacific Standard. “Transect placement is determined based on the influencing factors of the coastal analysis,” a spokesperson said—but conceded that two of the principal factors are “development type” and the number of structures.

Once he has a detailed, accurate map in ArcGIS, Bob simulates massive storms. “I’ll run the wave model, and I’ll contour wave height for a 100-year storm,” he told me. “What I’m essentially doing is looking at wave transformation as it moves into shore, and then challenging what FEMA says. They might say it’s going to be 20 feet high, but in the software I bring in a 100-year storm, and I might say, ‘No, it’s going to be 10 feet high.'”

Finally, he makes a determination about likely storm surge, studying a combination of factors like wave height, wave set-up, and how waves interact with the topography of the seabed and shoreline, then overlays those water levels onto topographical maps showing the elevation at which a home or building sits. According to Bob, when the agency remapped the coastline, these calculations were carried out with varying degrees of precision—and with techniques developed for a certain sort of coastline, which Maine doesn’t have.

“When they’re low on money, they always turn to a way that’s conservative,” he says. “They used this method that was developed from empirical observations on the West Coast. And the thing is, it just doesn’t prove useful in Maine.” A FEMA spokesperson noted that this method “was initially identified as being acceptable for use in FEMA’s West Coast Guidelines & Standards,” and that “after being studied by academia and engineering firms, it was listed in FEMA’s 2006 Atlantic and Gulf Coast Guidelines & Specifications as an acceptable methodology for use in those geographies.”

Before taking me to catch the ferry, Bob showed me his favorite place for watching storms, a boulder-strewn cove called Boom Beach. Sometimes, he said, when the storms got particularly fierce, he liked to walk down to film big waves on an old VHS recorder. He pointed to a nearby cliff. “That has an elevation of about 20 feet. During one storm the waves were breaking over that outcropping.” Now, he gestured to a rocky promontory. “Then going up to the tops of these 60-foot spruces at the top of that cliff. Just spectacular.”

It was amazing to me that a person who made his living measuring the dangers of the ocean would get so close to the water in conditions like those. What is it about the ocean that draws us in, I asked, even knowing the risks?

Bob shrugged and rolled his eyes a little at the question. “Human nature,” he said. “What can you do?”

In the Stonington town hall, Kathleen and several other officials sat before a crowd of about 70 people on the second floor, explaining why it would be in the town’s best interests to hire Bob Gerber. “Think of it like a new road map, but for the water,” Kathleen said at the end of her presentation. “The coast of Stonington is complicated, and FEMA apparently didn’t have the budget to study it in much detail—which means if we want to correct our maps, we’re going to have to hire a consultant to do it.” She explained that Bob had successfully remapped other towns, and that his updated maps had been approved by FEMA. Then she paused: “We’re not sure how the town’s going to pay for it. Maybe you all have some thoughts.”

Hands immediately went up. The crowd was a mix of what I’d call locals—people who’d spent all or almost all of their lives there—and more recent arrivals, whom some Mainers refer to as “from away.” And at first it was mostly these people from away who asked questions. They wanted to know whether their waterfront properties would be affected and whether they would personally be responsible for carrying flood insurance even if they didn’t have a mortgage.

After a few such questions, Kathleen sighed. “This is about the whole town,” she said. “Right now, anyone with flood insurance has a subsidized rate. But that’s going to end. You’re all going to have to make some drastic decisions. We have nothing budgeted to do this.”

An older lobsterman in a red cap spoke up: “Let’s say we go with this guy here you’re talking about. Six months later he wants more money, what then? When does it all stop?”

A poker-faced woman named Evelyn who served on the Board of Selectmen, an arm of local government, stared at the man. “The value of all the downtown waterfront together is $27 million,” she said. “The new maps put the whole thing in a high-velocity flood zone. Even if those properties get devalued, we as a town will still require the same amount of tax money to function. Everyone’s taxes will go up. Again.”

Outside the windows, the light began to fade, and fog slipped in off the water. The discussion turned into a debate about whether the whole town should pay for remapping parts of the waterfront, or just the people who owned those properties and were directly affected.

A tall, graceful, older man chided those who didn’t want to spend the money: “In my co-op in New York City, people didn’t complain about paying for things they didn’t directly use, like services for children.” The wife of a fisherman shook her head, a thick, reddish ponytail threaded through the back of her baseball cap. “This whole thing just looks like a money thing to me. If they can’t give us a map we can read, who are we to pay for a new one?”

By this point, Kathleen’s face had flushed pink like a sunburn. She reminded the crowd again that maps wouldn’t just affect private-property owners but the whole town. “This stuff is scary,” she said. “For all of us. These maps mean property values will be going down all along the coast. Don’t think it won’t happen here too.”

A pile of maps sat before her and now she pressed her palms onto the stack of paper as if containing it. “We should have accurate maps. And a lot of these maps simply aren’t correct,” she said. “The point is, if we’re not on the docket, we’re dead.”

Heading inland, the make-up of Maine quickly shifts. In a town like the one I grew up in, for instance, there are no summer people. For most Mainers, summer is just a season and not a verb. We stay put for winter. And during the first weak days of spring, we’re disproportionately grateful for any sign of warmth. The morning I went to meet Sue Baker, Maine’s National Flood Insurance Program coordinator—who oversaw the rollout of the new FEMA maps in the state—it was shaping into that sort of early spring day that only someone who’d been around for winter could fully appreciate. Cold wind, naked trees, dirty sky. In the downtown of Augusta, the state capital, a shirtless white man in jeans and unlaced boots strolled as if it were leisure, the only pedestrian in sight.

Though it was only 8:30 a.m., phones at the NFIP office were already ringing, and everyone seemed harried. Sue waved for me to sit, then returned with a stack of pamphlets and a thermos-sized cup of Dunkin’ Donuts coffee.

“There’s a lot riding on these maps for people,” she said. “These determine when flood insurance is necessary as a condition of financial lending. Statistically, if you’re in this area, you have a 26 percent chance of a flood over the course of a 30-year mortgage.”

I told her that I understood how a home in a floodplain that required costly insurance would no doubt be less desirable to buyers than one out of the floodplain, but I was most interested in accuracy. How had it come to be that so many of the FEMA maps were simply wrong, and that the process of correcting them seemed to place an unreasonable burden on towns and individuals?

“Money is probably the No. 1 factor here,” she said. It was often hard for people to face the fact that they would have to pay out of pocket if they wanted better maps, harder still to accept that revised maps would bring refunds on any flood insurance they’d already paid, but they would never recoup the cost of the remapping itself. “I usually just encourage people to consider that cost—if there’s a good chance they can get removed—compared with however much they have to pay in flood insurance.”

(Photos: Bob O’Connor)

(Photo: Bob O’Connor)

But, I asked, doesn’t that mean people and towns with more resources are more likely to contest the maps and get more accurate ones made? Wasn’t it surprising that the system was effectively targeting people with some of the longest histories in Maine and the least economic privilege?

“I’ve been here for 20 years,” she said. “I don’t think anything has been surprising.”

But it costs money to amend the maps, I insisted, and some people have more than others. Wouldn’t that put wealthy people in a better position to benefit?

“Certainly, there are people who have more resources,” she said, pushing back her chair as if to show that we were finished. “Another part of the legislation that passed says that an affordability study needs to be done, so that’s going to happen down the road.” She trailed off, then offered the brochures she’d brought along.

“I’m sure somewhere in here there’s language about all that,” she said.

There wasn’t. And FEMA only released an affordability framework in April of 2018, four years after towns were confronted with the new maps.

Everyone I spoke to—experts, state officials, residents, real-estate agents—agreed that reading the new FEMA maps in any detail without expertise and expensive software is difficult, and that contesting them without expertise and expensive software is impossible. And FEMA wasn’t broadcasting the fact that many maps contained errors, at least in part because it couldn’t know exactly if and where errors had occurred until a private consultant was hired by a town or individual. (Again, FEMA disputes this: “Throughout the flood-map update process, FEMA applies a rigorous eight-step quality review process, which includes independent reviews,” it said in its statement.) So to be “on the docket,” as Kathleen had put it, town officials not only had to identify potential problems on their own, but they had to allocate time to consider their options and money to hire experts to make corrections.

I wanted to visit another coastal town that, like Stonington, was largely working class and stood to benefit from getting more accurate maps but that had already decided not to pursue consulting. Yet the very nature of the problem made it impossible to know who would have benefited without a consultant having been hired, so I emailed Bob Gerber and asked for his help: “Of the towns that have been included in the remapping (and you haven’t already remapped), where might you suggest I look to find one that will be strongly affected by FEMA’s maps?”

A week later, he wrote back to say he’d reviewed the maps and settled on an island called Vinalhaven, not far from Stonington. He said the new map would be a “big change” for the town, “first because the zone is upgraded to a high-velocity zone with much higher insurance rates and zoning restrictions, and second because of the increase in elevation from two to four feet in what is a relatively flat-lying harbor with most of the buildings close to the water.”

I went out to Vinalhaven on a gusty day in early March, nearly a year after Bob sent that email. The gap was not intentional: Soon after moving back to Maine, several outlets for which I regularly freelanced fell late on paying invoices, so I took a job waiting tables at night—and a few months in, I fell down a set of rickety stairs at the restaurant and was injured too badly to work. But even a year later, Vinalhaven still hadn’t appealed its maps, which were set to be approved by FEMA the following summer.

After about an hour-long, choppy ferry ride, the weather calmed on the approach to the island’s harbor. I pressed my forehead against the cool, greasy window. Outside, sky and water were different shades of gray-blue, divided by a line of creamy granite, stained by bracken at the waterline and topped by spikes of spruce. I found myself surprisingly moved by the combination of geography and isolation, and wondered if it was this feeling that drew so many people to Maine. If I’d grown up elsewhere and come from money, perhaps I’d even feel like a second home here was a perfectly reasonable, uncomplicated thing to have.

From the dock, I went on foot to find Andrew Dorr, Vinalhaven’s town manager, who was 28 at the time. He wore a dress shirt under a fleece and looked even younger than his age, but it was immediately clear that he took the job seriously. Other officials and he had been studying the maps for months. As far as they were concerned, Andrew said, the new FEMA maps were a done deal and always had been.

“We probably should have looked at this closer,” he said. “But it’s hard to know the impact, and this is just one of those things you can’t fight.”

Andrew said he moved to Vinalhaven in 2008, right at the start of the Great Recession, desperate for work. The first year, he tended bar and spent the winter building lobster traps. Later, he worked as interim town manager, then got offered the position full-time. And now he was tasked with figuring out how to deal with a giant government bureaucracy. The appeals period had already passed, but the town still needed to figure out which houses were in the new floodplain and notify their owners that soon they’d be obligated to carry additional insurance. There hadn’t even been a public hearing to discuss the maps. This, Andrew reminded me, was because Vinalhaven didn’t have funds to hire a consultant like Bob Gerber even if it wanted to.

“I’m still trying to understand them,” he said of the maps. “A lot of the flood zone is commercial: All of Main Street, which is basically a causeway that was built in the late 1800s. The fish houses. The buying stations. The fishermen’s coop. A lot of the fish houses are owned outright. So on one hand, they won’t be obligated to get flood insurance, but if something happens and they have no insurance, it’ll be a total loss for them.”

(Photo: Bob O’Connor)

I was immediately struck by how different Vinalhaven’s situation seemed compared to towns that hired Bob. Until our conversation, Andrew said, he hadn’t realized the “VE” on the maps referred to high-velocity flood zones—or that private consultants like Bob weren’t just contesting the elevations of structures, but calculating and using more nuanced figures like wave set-up. What Bob Gerber and Kathleen Billings and even Sue Baker had said was now obvious: The maps were impossible to verify or challenge without a professional. It seemed clear Andrew was doing his best. But for interpreting the new FEMA maps, his best—anyone’s best, if they weren’t trained to do this—just wasn’t enough.

I asked if I could spread out the maps and look at the area around Main Street and the harbor that Bob told me should have probably been remapped, so we moved to a larger table. But when I started to page through the pile, those specific maps were missing.

“They might be up at the school,” Andrew said.

Still trying to see if they were just stuck at the back of the pile, I asked why.

“We asked the middle school students to help us figure this out.”

I paused and looked up, waiting for him to continue.

“I figured we could use all the help we could get. The kids are supposed to be learning about sea-level rise anyway. So I said: ‘Hey, we’re doing some downtown planning, and sea-level rise is part of it. Maybe you guys can help us identify some issues and potential solutions.'”

I told him I’d learned that the maps don’t actually project for sea-level rise. They just show the floodplain in the event of a 100-year storm, which was calculated using past data, not future projections. Andrew smiled faintly. I asked what the middle schoolers had come up with.

“Not much,” Andrew said. “More or less what you’d expect.”

In the end, expectations were exactly the issue. It’s not just FEMA, but what we, as a society, expect when it comes to who deserves what. All over the country, not just in rural Maine, those with a certain level of wealth and privilege enjoy not only greater luxury, but greater security, be it in the form of health care, education, immigration documents, or even the map that says whether we can continue to afford the place where we live. And what happens to you, if you don’t have enough money to buy that security? In the end, Vinalhaven decided that they had no choice but to let the process run its course.

But Stonington decided that they couldn’t take that chance. They hired Bob Gerber to challenge the FEMA maps, contesting the high-risk designation assigned to the downtown, Moose Island, and Burnt Cove. Through Bob’s work, the downtown and Moose Island were restored to low-risk status. After that, he stayed on to help the town develop a new comprehensive plan. All through the summer of 2017, Bob guided town officials and local volunteers through each section of the state regulations for such plans, gathering the necessary information and overseeing the composition to ensure its compliance with state rules. In February, the state approved the plan. For the first time in decades, Stonington will be able to apply for certain state and federal funds to aid in infrastructure and development projects needed to keep the town alive.

“It’s sad that we had to do this because of somebody else’s mistakes,” Kathleen Billings told the local newspaper of the remapping process. “But I’m still glad we did it. I think it was money well spent.”

This story was supported by the Reporting Award at New York University’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute and the Fund for Investigative Journalism.