(Illustration: Kevin Budnik)

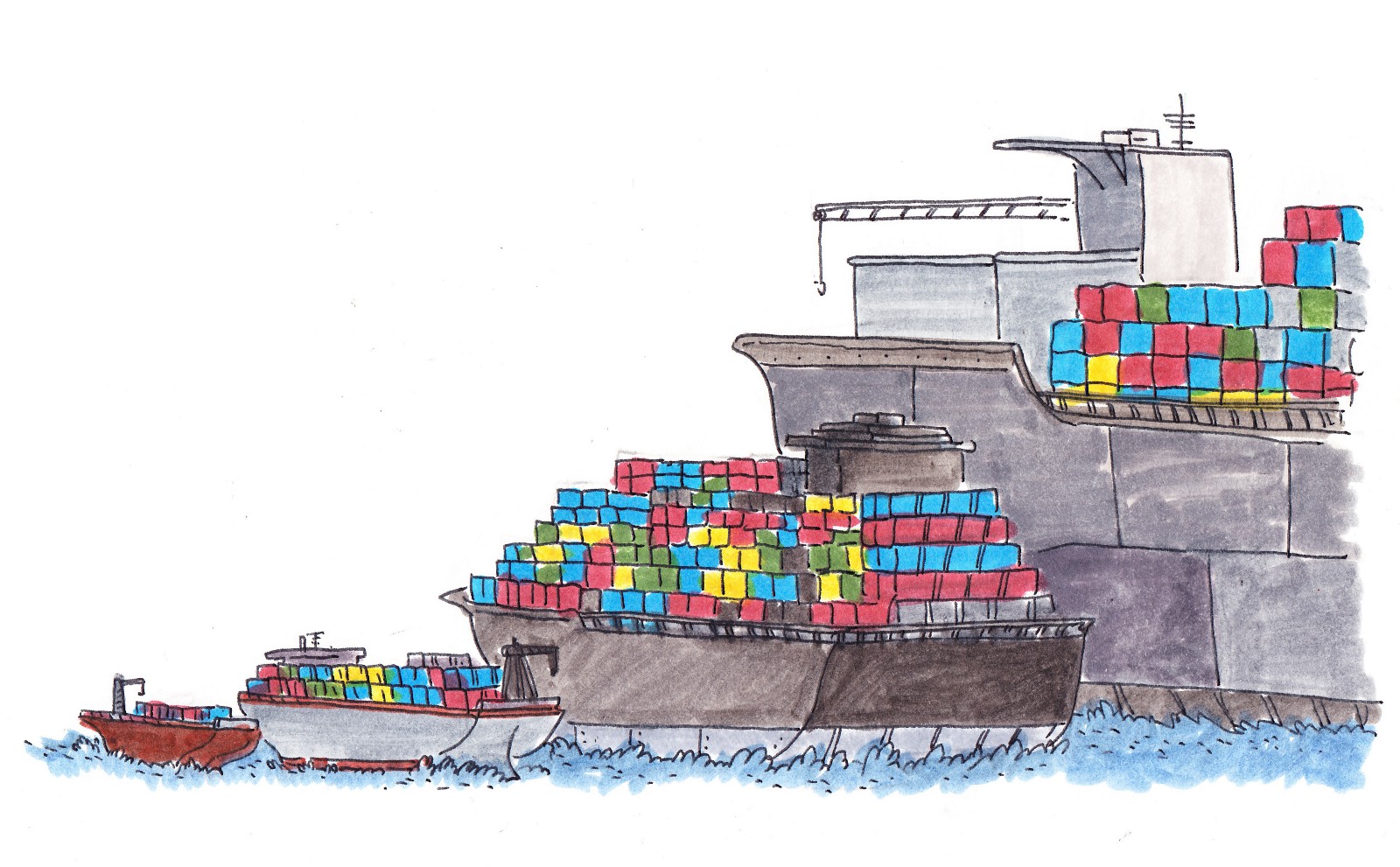

Here’s the thing about the shipping industry: It’s largely invisible to the land-locked public. For decades, the industry has operated with little public scrutiny — out of sight, out of mind. And while most people consider boats an outdated mode of travel, they are still a major mode of trade: More than 50,000 merchant ships are currently in operation across the world’s oceans, ferrying 90 percent of the world’s trade between producers and consumers.

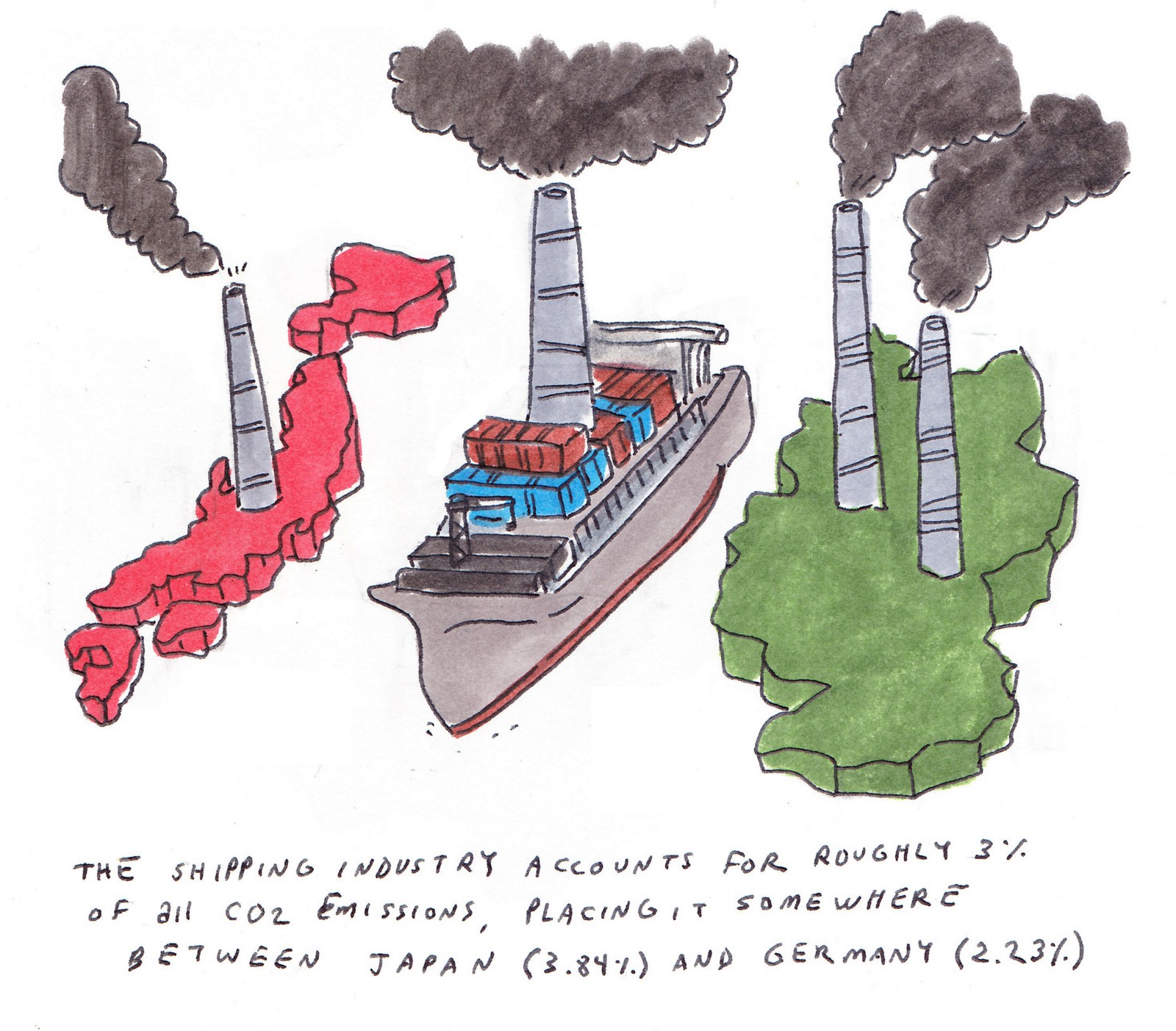

Shipping is by far the most energy-efficient and environmentally friendly way to move commodities in bulk — moving one ton of cargo by sea emits four times less carbon dioxide than moving it by road, and 100 times less than by air. But that hardly means that the industry is green. If the shipping industry were a country, it would be the sixth-largest emitter of carbon dioxide in the world.

Shipping emissions could grow by as much as 250 percent over the next few decades, accounting for 17 percent of global carbon emissions by 2050.

The shipping industry, already the fastest-growing source of emissions in the world, is expanding, in terms of both the size of fleets and their capacity. There are four times more ships at sea today than there were roughly a quarter-century ago. In the middle of what was the largest shipbuilding cycle in history — according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development — shipbuilding peaked in 2011, when the size of the world fleet increased by nearly 10 percent; in 2014, the world fleet grew by 3.5 percent. The biggest container ships at the turn of the century carried roughly 8,000 shipping containers; today, the biggest ships can carry over 19,000. While nations around the globe buckle down on emissions post-Paris, shipping emissions could grow by as much as 250 percent over the next few decades, according to a report from the International Maritime Organization, accounting for 17 percent of global carbon emissions by 2050, if maritime business continues as usual.

So why was the shipping industry left out of the Paris Agreement? The simple answer is, it’s hard to pin emissions from shipping on any one country.

(Illustration: Kevin Budnik)

Flags of Convenience

Every merchant ship on the seas must be linked to a country — its flag state. These ships are effectually floating territories, subject to the laws, regulations, and protection of their flag state, whether the ships are cruising international waters or calling into foreign ports. Once upon a time, a nation’s merchant fleet was made up of ships owned by domestic businesses, and crewed by its own citizens. That time has passed. As the world globalized, so too did the maritime industry.

Things got complicated with the advent of what the industry calls “open registries” — a.k.a. “flags of convenience,” a.k.a. countries that beckon foreign-owned, -operated, and -crewed ships to fly their flags, and thus live up (or down) to that country’s safety and environmental regulations. That’s how Panama, for example, accounts for a full 18 percent of the world’s merchant fleet by tonnage with more than 8,000 registered ships, some of which may have never even visited a Panamanian port. (From the beginning, flags of convenience were cloaks, used to skirt regulations: In the 1920s, the first foreign ships to take up the Panamanian flag were passenger vessels from the United States that served alcohol during prohibition.)

So let’s say a German ship, flying Panama’s flag, with a British captain and a multinational crew, transports goods from China to the U.S. Which country should take responsibility for those emissions? The U.N. created an organization to help sort that out.

The International Maritime Organization

As flags of convenience flourished throughout the 20th century, the need for an international body capable of overseeing the convoluted world of seaborne trade became ever more pressing. In 1948, the U.N. created a specialized agency, today called the International Maritime Organization, to oversee maritime safety and reduce pollution. The convention that created the IMO came into force a decade later, after it was ratified by 21 countries, and the IMO held its first meeting in 1959.

Some of the earliest negotiated regulations for shipping came in response to episodic disasters like oil spills. “The initial regulations for environmental performance in shipping had to do with maintaining safety conditions such that pollution episodes and catastrophes would be prevented, avoided, or minimized,” says James Corbett, a professor at the University of Delaware’s School of Marine Science & Policy. “So dumping and discharges and spills and accidents were front and center in the environmental attention that the shipping industry had.”

MARPOL — a convention for the prevention of pollution by ships — was enacted in 1983. At that time, the convention included new regulations to avert oil pollution from both spills and regular operation, and to control the discharge of “noxious liquid substances.” Over the years, MARPOL has been amended to provide guidelines for the control of other potential pollutants. It wasn’t until 2005 that an air-pollution annex was added.

(Illustration: Kevin Budnik)

A Wave of New Data

It wasn’t just a lack of public interest that limited the IMO’s regulation of more routine environmental impacts like ballast water discharge, emissions, and energy efficiency; it was also a lack of data. In fact, much of the data that has sparked and informed the current conversation around the environmental impact of shipping was gathered by unsuspecting scientists who were trying to study something else.

In 2006, for example, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration researcher Daniel Lack was aboard a research vessel in the Gulf of Mexico, trying to measure black carbon levels in the atmosphere. But ship plumes kept getting in the way, as Rose George reported in her 2013 book about the shipping industry, Ninety Percent of Everything. Lack was annoyed, according to George, until he realized how little data existed on ship plumes: No one was tracking exactly what was coming out of ships on a large scale. Lack’s work led to the first global estimate of just how much particulate matter the shipping industry was adding to the atmosphere. Research from other scientists has shown that emissions of particulate matter from ships cause roughly 60,000 premature deaths from cardiopulmonary issues and lung cancer every year.

Around the time Lack was accidentally measuring ship plumes, Jean Tournadre, a researcher at Ifremer, the French Institute for the Exploitation of the Sea in Plouzane, was using altimeter data collected by satellites to identify icebergs in cold, polar waters, when he noticed that he could track something else with his data: ships. Tournadre used satellites to track global maritime traffic between 1992 and 2012. Over those two decades, ship traffic increased everywhere. Even the global economic crisis in 2008 could not reverse this trend; only off the coast of Somalia, where piracy picked up in 2006, did ship traffic ebb. Over this 20-year period, traffic grew by 300 percent in the Indian Ocean, home to some of the busiest shipping lanes in the world in the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal. Similar growth rates in the western Pacific Ocean and China seas reflect the growing importance of China in global trade. Meanwhile, traffic in the Atlantic and northern Pacific Oceans grew by as much as 200 percent.

What does all that extra fuel mean for the environment?

(Illustration: Kevin Budnik)

Filthy Fuel vs. ‘Slow-Steaming’

Bunker fuel is essentially a residue — a thick, dirty sludge left behind at refineries after other fuels have been removed. “It is so unrefined,” George writes, “that you could walk on it at room temperature.” Nearly all of the carbon in bunker fuel is converted to carbon dioxide as it burns (which gives researchers a handy way to estimate carbon dioxide emissions based on how much fuel ships use), but the black clouds of smoke that pour out of ship stacks also contain nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, trace black carbon, and particulate matter.

Luckily, shipping companies don’t want to burn a lot of bunker fuel — not because it’s bad for the environment, but because it’s incredibly expensive. Fuel is by far the largest operational cost to shippers, according to Simon Bennett, the director of external relations with the International Chamber of Shipping. One way to burn less fuel and save more money is just to slow down. This practice is called “slow steaming, and it can also cut down on carbon emissions. “The latest IMO greenhouse gas study shows that the total carbon dioxide emissions from international shipping actually reduced by 10 percent between 2007 and 2012 and that was despite the amount of shipping actually increasing still in that period,” Bennet says. “That was primarily a result of ships going at slow speeds.”

Slow steaming allows ships to burn less of a dirty fuel, but it could only ever be an incomplete remedy.

The Sulfur Problem

Burning bunk fuel produces the same pollutants as those produced by vehicles on the road, but the difference is, the amount of sulfur and nitrogen oxides that cars and trucks can emit has been strictly limited for decades. “Before 2010, ships could burn fuel with a sulfur content of 4.5 percent — very dirty, very cheap,” Maritime Industry Consultants’ John Graykowski said in a 2015 Brookings Institution panel on shipping. “By comparison, in 2010 the U.S. [Environmental Protection Agency] limited on road diesel fuel to 0.15 percent.” As a result, marine fuel contains thousands of times more sulfur than the diesel fuel that powers vehicles on the road, and sulfur and nitrogen oxides released from bunker fuel pollute the atmosphere while also increasing ocean acidification along major trade routes and causing tens of thousands of early deaths.

To address these widely known impacts of sulfur on the environment and human health, in 2012, the sulfur limits for maritime fuels went down to 3.5 percent and, in 2015, the IMO created emissions control areas, in which member states could enact more stringent regulations in the water off their coasts. Today, off the coasts of the U.S., Canada, and northwest Europe, ships can only burn fuel with less than 0.1 percent of the pollutant. By 2020, the sulfur content allowed in bunker fuel used outside of these ECAs will drop to 0.5 percent.

The maritime industry is slowly catching up to land transport regulations, but it’s not as if the IMO disregards the urgency of lowering emissions — it’s just that each new regulation can take years of negotiation.

An Uneasy Alliance

Today the IMO has 170 member countries, and it rules by consensus. While domestic organizations like the EPA can establish new regulations and set timelines for those new standards with an executive authority — in other words, without full approval from the regulated industry — the IMO requires ratification of new standards by member nations. Then each nation implements domestic laws that comply with the IMO standards.

“It’s a slower process by design,” Corbett says, “not by some sort of nefarious mistake or villainy.”

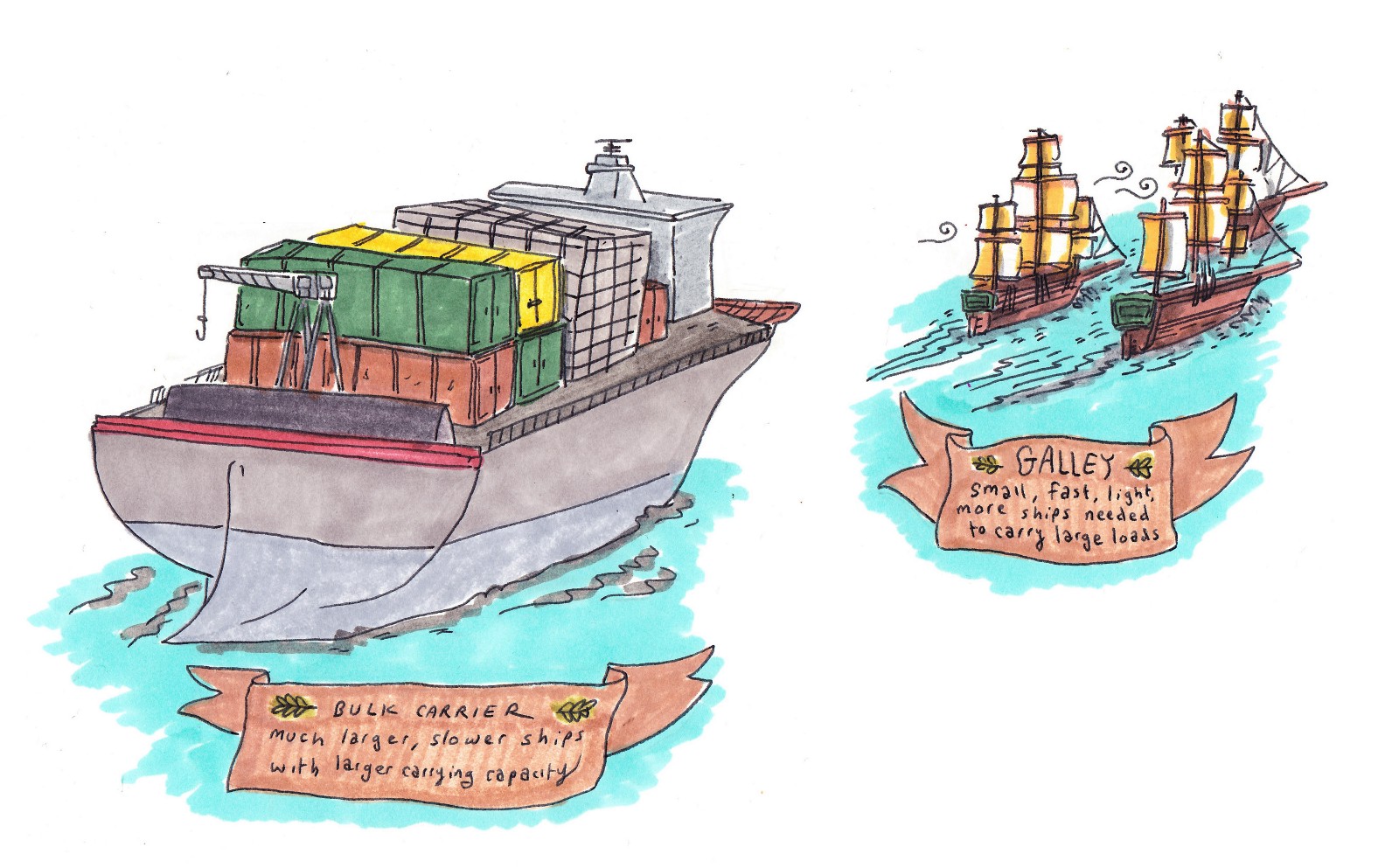

Bear in mind that the majority of the current global fleet was built to run on bunker fuel, and ships can have decades-long lifespans. Every new regulation requires not only cooperation by the IMO member states, but also technological innovations and often design modifications for existing ships to bring them up to new standards. Corbett likens the current energy transition the industry is undergoing to the transition from wind-powered ships to engine-powered ones. “One hundred years ago the industry was similarly experimenting with lots of options as it moved away from sail,” he says. “These transitions require decades of innovation and trial and error, and so, in some ways, we’re in the beginning of a period of shaking out of the possible solutions.”