In 2014, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio decided to adopt Vision Zero, a multi-national initiative dedicated to eliminating traffic-related deaths. Under Vision Zero, city services, including the Department of Transportation, began an engineering and public relations plan to make the streets safer for drivers, pedestrians, and cyclists. The plan included street re-designs, improved accessibility measures, and media campaigns on safer driving.

The goal may be an old one, but the approach is innovative: When New York City officials wanted to reduce traffic deaths, they crowdsourced and used data.

Many cities in the United States—from Washington, D.C., all the way to Los Angeles—have adopted some version of Vision Zero, which began in Sweden in 1997. It’s part of a growing trend to make cities “smart” by integrating data collection into things like infrastructure and policing.

Cities have access to an unprecedented amount of data about traffic patterns, driving violations, and pedestrian concerns. Although advocacy groups say Vision Zero is moving too slowly, de Blasio has invested another $115 million in this data-driven approach.

De Blasio may have been vindicated. A 2015 year-end report released by the city last week analyzes the successes and shortfalls of data-driven city life, and the early results look promising. In 2015, fewer New Yorkers lost their lives in traffic accidents than in any year since 1910, according to the report, despite the fact that the population has almost doubled in those 105 years.

Below are some of the project highlights.

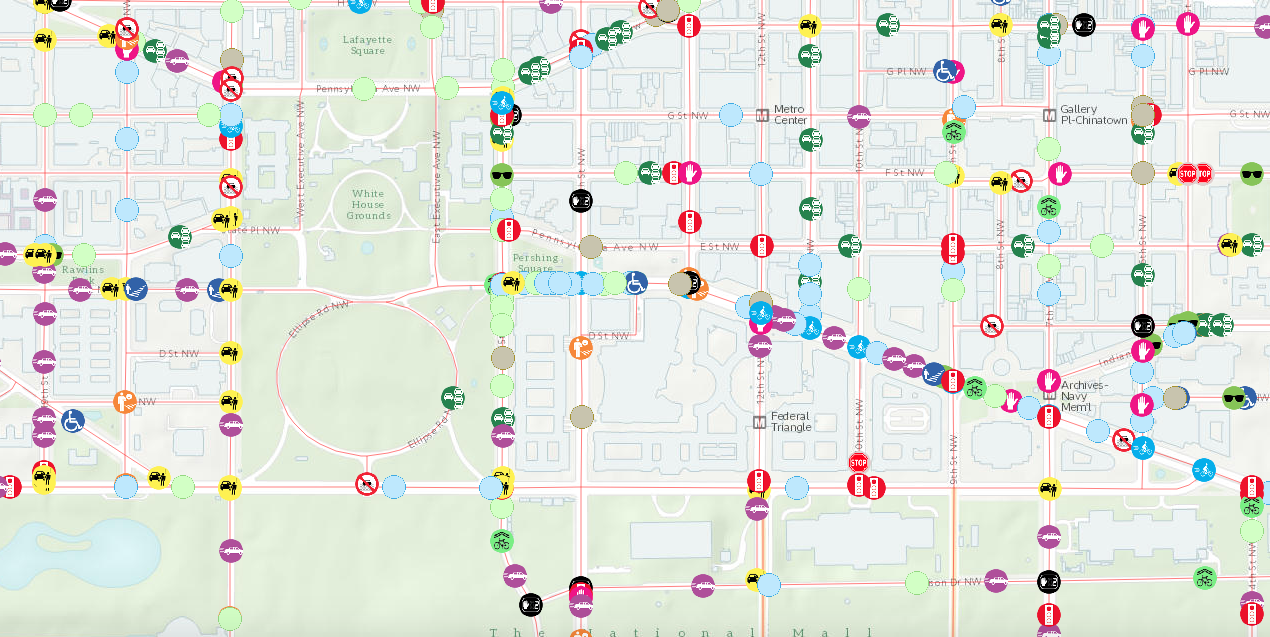

New Yorkers were invited to add to this public dialogue map, where they could list information ranging from “not enough time to cross” to “red light running.” The Department of Transportation ended up with over 10,000 comments, which led to 80 safety projects in 2015, including the creation of protected bike lanes, the introduction of leading pedestrian intervals, and the simplifying of complex intersections.

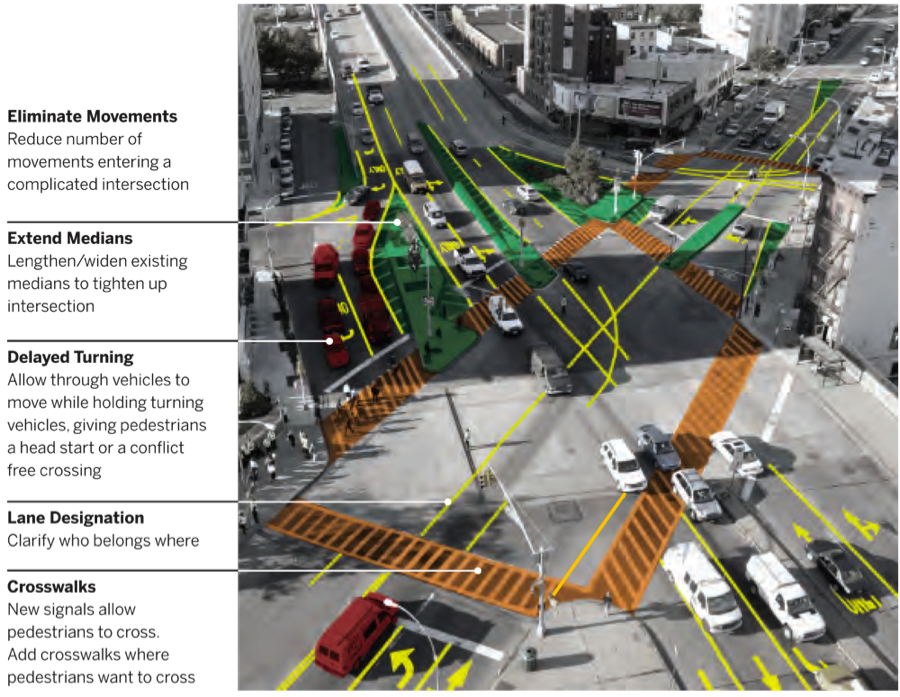

Data collected from the public dialogue map, town hall meetings, and past traffic accidents led to “changes to signals, street geometry and markings and regulations that govern actions like turning and parking. These projects simplify driving, walking and bicycling, increase predictability, improve visibility and reduce conflicts,” according to Vision Zero in NYC.

The illustration above shows changes made at Jackson Avenue from 11th Street to the Pulaski Bridge in Queens. Crashes resulting in injuries were reduced by 63 percent after the changes were made. This past year, 2015, was the safest year for New York City pedestrians, with 134 deaths.

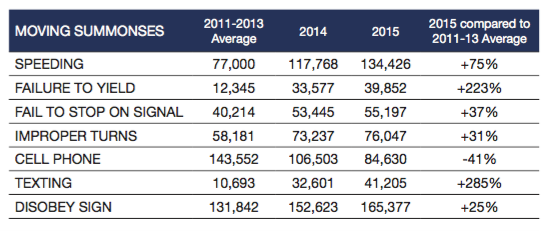

The city has also streamlined the policing process and cracked down on traffic violators. In the report, the city claims increased ticketing as a success. The Department of Transportation tracked the license plate numbers of people who received speeding tickets and found that 70 percent of them didn’t violate again within the 18-month period studied.