Soon into Alice Albinia’s journey along the Indus River, she watches as a boat sets out into a main channel, where the water is believed to be the purest. A woman on board throws what looks like a bundle of cloth into the river; it “twists on the surface in a blur of red and gold.”

When the woman returns to shore, Albinia asks what she was doing.

It’s a blessing to throw it in the river, the woman says. “Throw what?”

“The Qur’an.”

Even though she has witnessed people’s extreme devotion to the Indus at shrines throughout her journey in Pakistan’s Sindh province, Albinia is stunned at this act of the profane mixing with the sacred. The woman looks scornfully at Albinia. “You can read and write — and still you do not understand,” she says.

Empires of the Indus:The Story of a Riveris Albinia’s recklessly ambitious journey to try to understand what makes this river so holy. The Indus, often referred to as “the mighty Indus” in common parlance, served as the backbone for the region that is now made up of eastern Afghanistan, Pakistan, northwestern India, and the Tibetan plateau — it flows for nearly 2,000 miles through South Asia. It fostered civilizations and dynasties and major religions, including Hinduism, Islam, Sikhism, and Buddhism.

The Indus once fostered religious plurality in the communities that took root along its riverbanks. Vestiges of this still exist, but water is increasingly a source of contention.

Going in, Albinia’s plan is to trace the course of the Indus in reverse, from where it ends up in the Arabian Sea near the Pakistani city of Karachi to its origins in Tibet. She trusts local guides and uses lore, ancient texts, and colonial-era documentation to plot her journey.

But this is not a straightforward sail up a river: To complete her quest, Albinia has to navigate borders and procure visas for four different countries, travel through farmland and militarized zones, and attempt to re-trace the steps taken by conquerors hundreds of years ago. And is there even an Indus for her to see? The river has been exploited by generations of invaders and colonizers, and is being decimated by the demands of urbanization. In Pakistan, the mighty Indus is used as a conduit for sewage, and its tributary in downtown Kabul, Afghanistan, resembles a trash-filled stream.

Albinia sets off by boat from Karachi, where a fisherman tells her that it will take a couple of days to sail to the mouth of the river because the delta is so dry. As she moves through Pakistan, Albinia finds a river forced into submission — and ancient texts offering a prescient warning about preservation.

Empires of the Indus, first released in 2008, reinforces this message by studying the people that inhabited and continue to live along the river’s banks. “If the Indus cities’ dependence on water ruined them,” Albinia writes, “then the story today may be mimicking that ancient plotline.” Albinia plays travel writer, historian, anthropologist, and journalist to turn this travelogue into a full-fledged exploration of the empires her title refers to. She offers fascinating vignettes of communities that practiced polyandry and worshipped river gods, a saint described as the “world’s first socialist,” and histories of invading armies and ancient Aryans.

The most remarkable experience is Albinia’s exploration of the lives of the Sheedis, the descendants of African slaves brought to India as early as 711 C.E. Her nuanced portrayal includes accounts of activists who take great pride in their roots, and a bride-to-be who tries to lighten her skin so she is not laughed at for her “blackness.” While living with Sheedi families, Albinia discovers that there is just one copy of a 1952 study detailing their history, and so she begins to translate the book into English to preserve this record.

ThroughoutEmpires of the Indus, Albinia’s curiosity leads her off on tangents that seem distracting at first, but that tie into the book’s sweeping mission to explore the interweaving histories linked to the river and the state of the lands it flows across. While traveling around Karachi, she sees an almost naked man emerge from a sewer, and stops to talk.

Pakistan, the man tells her, created a “social apartheid” to keep Karachi clean, thus setting into motion systematic discrimination against religious minorities. Shortly after Pakistan became an independent country in 1947, violence against Hindus and Sikhs engulfed Karachi. As Hindus fled to India, Pakistan responded by slowing down the migration of “depressed classes” — lower-caste Hindus and Christian converts — thus sealing their fate as cleaners of the sewers. Muslims considered the work beneath them, quite literally, and believed it would interfere with their prayers, so Christian and Hindu men were left to sweep the streets.

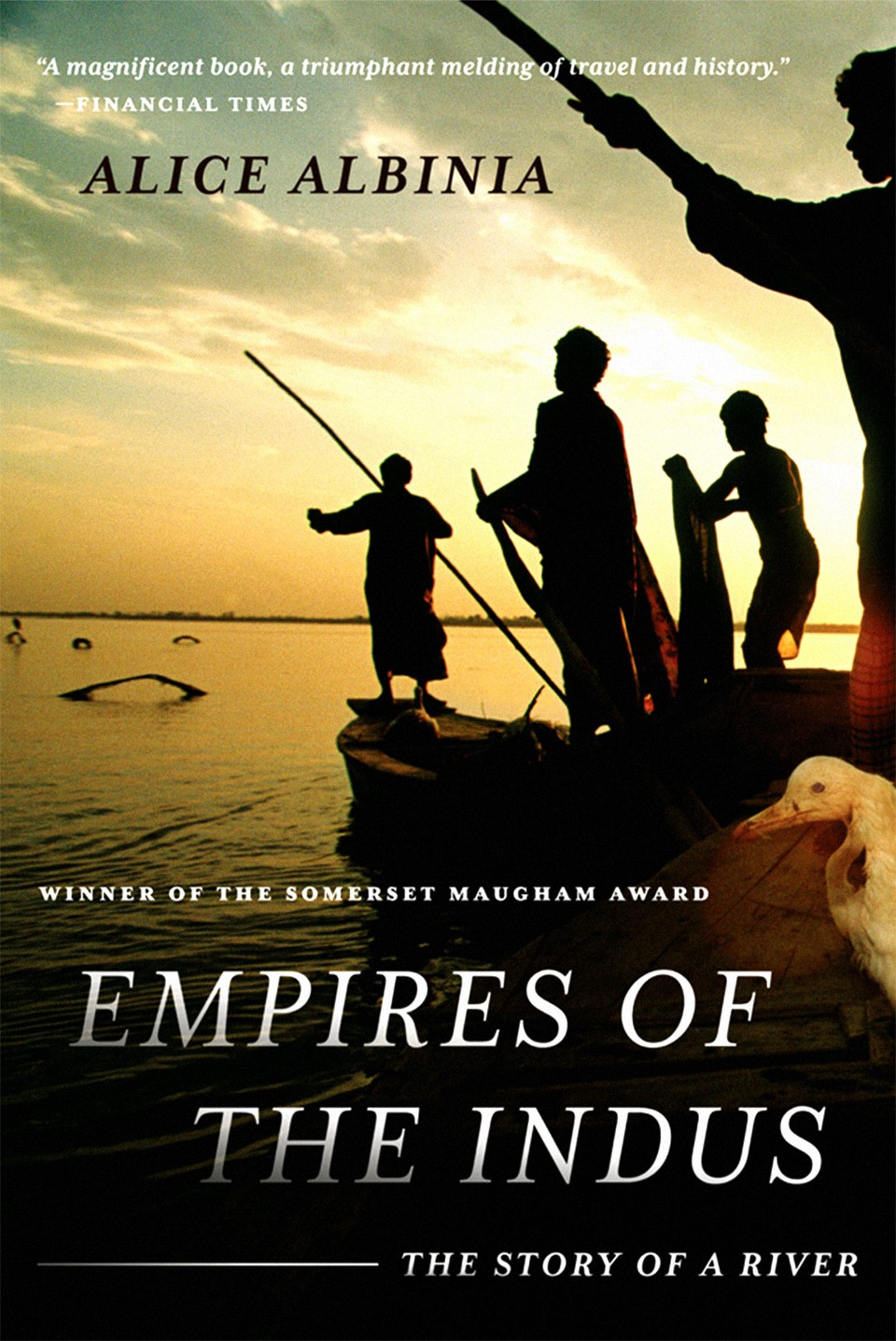

Empires of the Indus: The Story of a River. (Photo: W.W. Norton & Company)

This social apartheid continues to this day. The Indus once fostered religious plurality in the communities that took root along its riverbanks. Vestiges of this still exist, as evidenced by the widespread devotion shown to Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, a Sufi saint often referred to as Jhule Lal, one of the names for the Hindu god of water. But water is increasingly a source of contention, and recent events indicate that this conflict is tearing apart an already fragmented society.

In 2009, a Christian woman in Pakistan was accused of blasphemy and sentenced to death after an argument broke out as she fetched water from a well used by Muslims. Whether Muslims can refuse the use or sale of water is a matter of religious debate, and it is common to see Pakistani households maintaining separate utensils for their Christian or Hindu employees. Water has effectively become a tool to marginalize religious minorities.

This marginalization may be rooted in how the nations of Pakistan and India came into being, and how the Indus continues to play a role in their division. In 1947, British colonialists divided the Indian subcontinent into two separate countries, prompting a mass exodus across the new borders and communal riots that led to massacres and rapes. The division sparked a battle over identity and territory that continues to this day. Albinia uses her tour of the river to dive into this complicated, interconnected history.

The Punjab region — which is now divided between India and Pakistan and literally translates to Five Waters, after the five tributaries that flow through it — was historically a staging ground for the fights between the Indus’ many empires. It was a key region for the agrarian economy and at one point the center of power for the Mughal Empire. Battles between conquerors took place near the Indus’ tributaries and gave the river and the province a distinct military identity. “I shall strike fire under the hoofs of your horses,” Guru Gobind Singh, the revered Sikh religious leader, taunted the Muslim ruler Aurangzeb, from the Mughal dynasty, in the early 1700s. “I will not let you drink the water of my Punjab.” This mentality still exists in Pakistan, where Punjab is considered a jewel that must be protected and defended. In 2010, Shahbaz Sharif, the chief minister of the Punjab province, publicly stated that the Pakistani Taliban network shouldn’t attack Punjab, since Sharif ’s political party and the militant group were united in their opposition to Pakistan’s former military ruler, Pervez Musharraf. Sharif was later accused of trying to cut a deal with militant groups in exchange for the province’s safety.

The colonial rulers of the Indian subcontinent developed agrarian policies and systems that led to the inequitable distribution of resources in favor of Punjab, further bolstering its importance. The province was divided between Pakistan and India at the time of the countries’ independence, and the worst of the communal violence took place in the once-unified Punjab. Pakistani and Indian officials divided the Indus and its five tributaries among themselves, but the two countries are still arguing over disputed territory and water — with many Pakistanis accusing India of causing floods or building dams on the rivers.

This dispute stands in parallel to arguments over the Indus within Pakistan, where water resources are heavily contested between provinces. Pakistan continued the colonialist focus on Punjab in the post-independence years, to the detriment of the rest of the country. While this made Punjab prosperous, it also allowed it to stake an outsized claim over politics, produce, and the military, turning it into a symbol of tyranny in Pakistan.

Empires of the Indusis as much a lament for history as it is for the decimation of the culture surrounding the mighty river. During her journey, Albinia discovers ignored archaeological finds, including stone circles and ancient carvings; Buddhist statues that have been defaced and destroyed; and tombs disappearing into the desert. A villager in the Chitral region who has unearthed ceramics that may date back three millennia hands one over to Albinia as a gift to take away.

Albinia continues onwards and upwards — to the Swat district in northwestern Pakistan, where Buddhist history is buried under hundreds of years of silt, and where religious militancy is beginning to take hold.

Albinia’s travels take place in the post-9/11 years, and, while her personal security doesn’t seem to factor into her travels, the region’s militarized nature does. She has to negotiate with officials to visit disputed territories and former warzones so that she doesn’t stray from the river. As she struggles with border crossings and the right entry stamps for Afghanistan, Albinia has to choose a travel itinerary that will, as she puts it, “surely get us sent to jail, abducted by al-Qaeda or blown to pieces by a rogue Waziristani rocket-launcher.” (She is spared this fate after a well-connected friend introduces her to a series of passport officers, government officials, and escorts.)

Albinia is not the stereotypical awestruck traveler, and this is not a journey of New Age self-discovery. There is a great deal of self-deprecation about her obsession with the river. Albinia gets tired, is wary of situations, and becomes frustrated with the journey and her guides. When she reaches Tibet to find the source of the river, Albinia is convinced that she’s in the wrong place because she can’t see any water. With crying jags and time with an “eccentric drunk” as a guide behind her, she finally makes it to the mouth of the Indus. After the sweeping narrative of the book, this moment feels anticlimactic. Perhaps it is also appropriate. “The river is slipping away through our fingers, dammed to disappearance,” Albinia writes, as she offers her own warning to the Indus’ modern-day empires. “One day, when there is nothing but dry riverbeds and dust, when this ancient name has been rendered obsolete, then the songs humans sing will be dirges of bitterness and regret.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the May/June 2016 issue of Pacific Standard. Subscribe now and get eight issues/year or purchase a single copy of the magazine.