The economic recovery continues, but many workers still can’t find full-time work.

By Dwyer Gunn

(Photo: Tim Boyle/Getty Images)

In November, the unemployment rate dropped to 4.6 percent, the lowest its been on record since the recession—yet another indicator that the United States’ economy is slowly but surely continuing to recover.

Of course, signs of weakness persist. Labor force participation among working-age men is down, while most workers’ incomes are still below pre-2008 levels (though the median American household saw its income increase in 2015). But there’s a less-discussed aspect of the recovery: As a new report from the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank, highlights, too many part-time workers who want full-time jobs aren’t able to find such work.

“Over six years into an economic recovery, the share of people working part time because they can only get part-time hours remains at recessionary levels,” writes the EPI’s Lonnie Golden. “The number working part time involuntarily remains 44.6 percent higher than it was in 2007.”

(Chart: Economic Policy Institute)

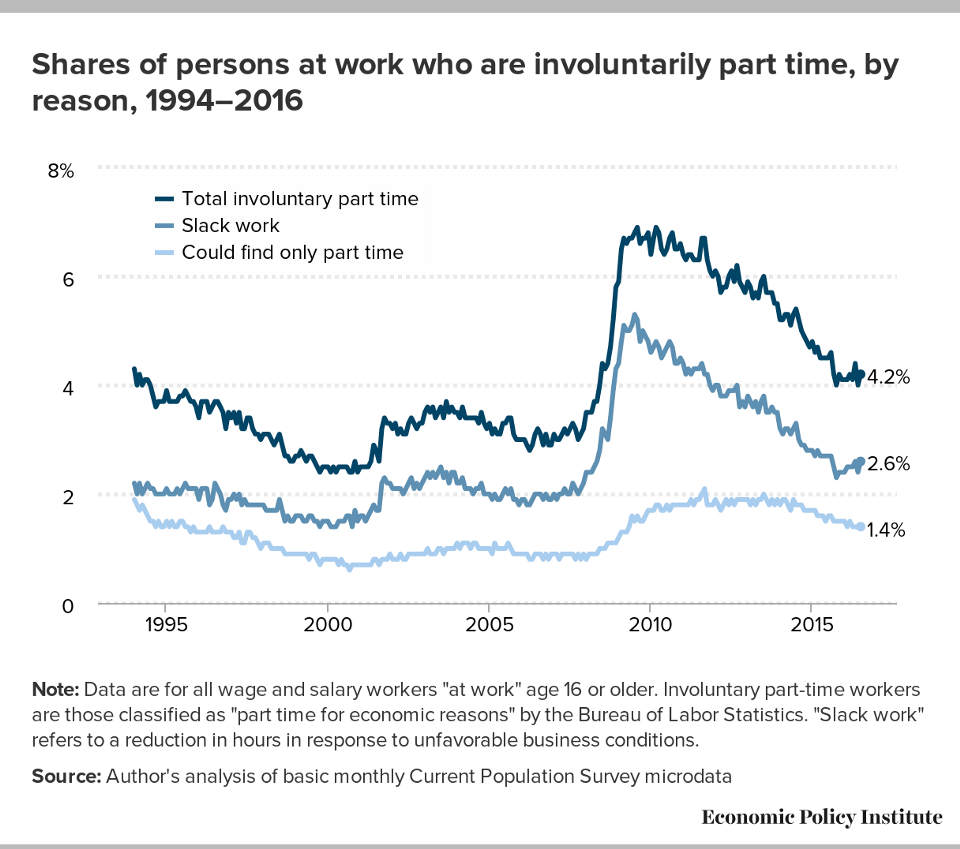

The chart to the left, from the EPI report, illustrates the total share of the labor force in involuntary part-time employment, the share who are involuntarily part time due to “slack work or business conditions” (this category generally reflects cyclical economic trends), and the share who are involuntarily part time because they could “could find only part-time” work.

In the depths of the recession, the percentage of the workforce who wanted to work full time but couldn’t find such work due to economic conditions/slack was high. As expected, that percentage has declined sharply since 2010 as the economy has recovered.

The other category — the “could find only part-time work” category — has been more stubborn. The trend suggests, in Golden’s words, that “the currently elevated level of involuntary part-time working is no longer due largely to cyclical forces, and appears to reflect more than just the delayed and slow economic recovery.”

The report highlights two sectors that seem to be driving the trend — the retail industry, and the leisure and hospitality industry — and also finds that Hispanic and African-American workers are disproportionately represented among the ranks of the involuntarily part time.

So why do so many companies seem to prefer part-time workers these days? The EPI report points to a number of structural changes, including industry composition, population demographics, higher labor costs for full-time workers, and new technologies that make it easier and cheaper to manage part-time workers. The report also suggests a number of reforms that might reverse the trend:

Pay and benefits parity for part-timers; innovative soft-touch regulations providing workers with rights to request minimum and maximum weekly hours; fair scheduling practices and rights to access additional hours; minimum reporting pay and predictability pay; unemployment insurance reform; overtime regulation reform; and creating “steps” rather than a single “cliff” in the ACA Shared Responsibility provisions to cushion any potential unintended consequence of employers cutting work hours, even with the limited evidence of its occurrence.

Most of these reforms are likely to face significant resistance from a Republican administration and Congress. That’s a shame, because part-timers who want but cannot find full-time work barely outpace the unemployed in financial well-being.