Last week, Hillary Clinton unveiled a series of proposals to improve the affordability and quality of childcare in America. It’s about time.

By Dwyer Gunn

(Photo: Loic Venance/AFP/Getty Images)

While campaigning in Kentucky last week, Hillary Clinton announced several policies aimed at improving the quality and affordability of childcare in America. Clinton’s proposals call for an expansion of home visiting programs, higher pay for childcare workers, and increased assistance for low-income and middle-income families struggling to pay for childcare. Under Clinton’s plan, childcare spending would be capped at 10 percent of a family’s income.

“The cost of child care has increased by nearly 25 percent during the past decade, even as the wages of working families have stagnated,” reads a fact sheet on Clinton’s website. “And while families across America are stretched by skyrocketing costs, child care has become more important than ever before — both as a critical work support for the changing structure of American families and as an essential component of a child’s early development.”

Last month, the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank, released a report calling for an “ambitious national investment in America’s children” (their proposals look similar to Clinton’s). The report paints a grim picture of the state of childcare in America. In only two states — South Dakota and Wyoming — is infant childcare affordable (affordability is defined as requiring 10 percent or less of a family’s income). In Washington, D.C., center-based daycare for infants costs, on average, $1,868 a month.

Unsurprisingly, low-income families are particularly vulnerable. In D.C., for example, a minimum-wage worker would have to devote 103.6 percent of their income to infant care. Even in affordable South Dakota, 31.8 percent of a minimum wage worker’s income would be eaten up by the costs of infant childcare. These costs, as the Clinton campaign notes, have increased substantially in recent years.

In South Dakota, 31.8 percent of a minimum wage worker’s income would be eaten up by the costs of infant childcare.

In 31 states in America today, center-based childcare costs more than the tuition at a public four-year university, according to a report on childcare released last year by the Center for American Progress. Americans face higher childcare costs than parents in almost any other developed country, yet the federal government spends less on childcare than any other nation in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that making childcare more affordable has never been more important. As women have entered the workforce in growing numbers — either by choice or due to economic necessity — the number of children who are regularly cared for by non-family members has increased. Even the social safety net increasingly encourages, or requires, recipients to work in order to receive benefits. Today, over 12 million children under the age of five attend childcare every week.

But the other components of Clinton’s proposal — specifically, the efforts to increase the pay, qualifications, and training of childcare workers — deserve just as much attention. It is increasingly clear that the care a child receives in the early years of her life can impact, for good or bad, the way that child’s brain develops. High-income families are able to invest a good deal more time and money (about $7,500 more in 2006, in fact, according to the EPI report) in their children’s development, which means that low-income children enter kindergarten at a significant disadvantage to their higher-income peers.

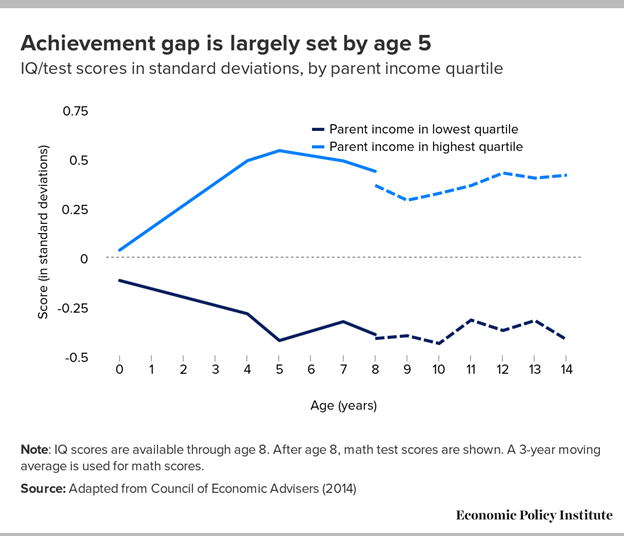

Most of those kids never catch up. This chart, from the EPI report, illustrates how achievement gaps evolve as children get older:

(Chart: Economic Policy Institute)

High-quality childcare can help close these gaps. Back in the 1990s, a team of researchers tracked second-graders who had attended center-based childcare in their early years. In a report summarizing the study, the researchers found that “[c]hildren who attended higher quality child care centers performed better on measures of both cognitive skills (e.g., math and language abilities) and social skills (e.g., interactions with peers, problem behaviors) in child care and through the transition into school.” The researchers also noted that more disadvantaged kids — specifically, those whose mothers had lower levels of education — were particularly sensitive to both the benefits of high-quality care and the negative effects of poor quality care.

Conversely, low-quality childcare can have the opposite effect — harming a child’s cognitive and social development and increasing the prevalence of problem behaviors later on. A study by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) on the effects of early childhood care concluded that “when groups are large, when there are many children to care for but few caregivers, and the training/education of caregivers is limited, the care provided tends to be of lower quality, and children’s development is less advanced.” This conclusion is consistent with a number of other studies that have found children in high-quality care settings are happier and perform better on social and cognitive measures than those in low-quality settings—and these effects can persist for years. According to the NICHD study, less than 10 percent of child care arrangements in the United States are rated as “very high quality.”

The U.S. does, indeed, need a grand new childcare plan, and Clinton is correct that this plan should involve more than tax credits. American parents don’t just need more affordable childcare; they need childcare that enhances the well-being and development of their children.

||